Upon assuming office in 2000, Mexico’s former president Vicente Fox inherited a border police agency so violent and so corrupt that he fired its entire workforce and repurposed its mission from law enforcement into an unarmed humanitarian service agency. While this move didn’t eliminate abuses by Mexican border police, Fox’s intervention at the time nevertheless accomplished a paradigm shift to Mexico’s approach to migration and border security. As the U.S. Congress debates the future of the United States’ own immigration and border policy, perhaps it is time that we consider a similar path. This is a case for why this is the most ethical course of action.

The Border Patrol’s Ingrained Culture of Cruelty

Since 2004, the southern Arizona humanitarian organization No More Deaths has documented U.S. Border Patrol agents committing human rights abuses, ranging from cruel, unsafe, and unsanitary detention conditions to physical and sexual assault. Independent research funded by the Ford Foundation verifies these findings, and concludes that at least 11% of individuals who pass through Border Patrol custody experience this kind of mistreatment.

On January 17, 2018, No More Deaths, alongside Tucson’s Coalición de Derechos Humanos, issued a new report which reveals how Border Patrol agents contribute to the widespread disruption of humanitarian efforts, including the destruction of 3,586 gallons of clean drinking water placed along migration trails between 2012 and 2015. Within hours of the report’s release the Border Patrol retaliated by raiding a humanitarian aid station in Ajo, Arizona and arresting Scott Warren, a professor at Arizona State University and No More Deaths volunteer, along with the two migrants to whom he was providing care. Warren now faces felony charges under a human smuggling statute. Less than a week later, eight humanitarian volunteers received indictments for leaving clean drinking water along the “Devil’s Highway” area of the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. These acts of retaliation appear to confirm the worst allegations about the Border Patrol, including that the agency’s institutional culture maintains a fundamental contempt for the sanctity of human life. This attitude is not new, but rather has been woven into the strategy of U.S. border enforcement since at least the early 1990s.

The Border Patrol’s Harmful and Counterproductive Deterrence Strategy

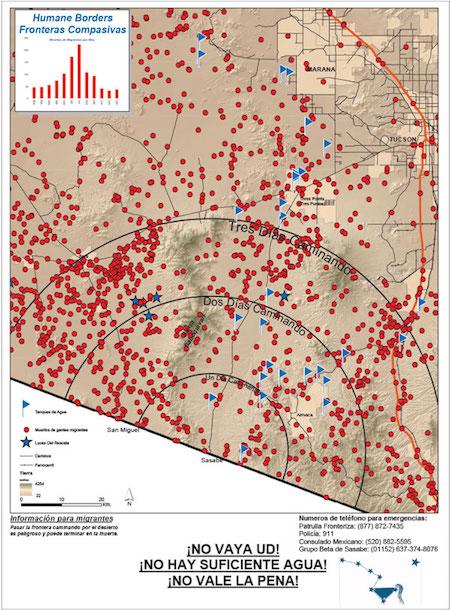

In 1994, the United States Border Patrol launched a nationwide enforcement strategy, described internally as “prevention through deterrence.” The logic governing this border strategy was simple and straightforward: by ratcheting up the hardship that unauthorized migrants endure along the journey north, they might be successfully “deterred” from crossing the border altogether. This outcome was to be accomplished by weaponizing the geography and terrain of the borderlands, and concentrating agents in urban areas to push migration routes into increasingly remote and treacherous areas. At the time, then-Immigration and Naturalization Services Director Doris Meissner said, “We did believe that geography would be an ally for us. It was our sense that the number of people crossing through the Arizona desert would go down to a trickle once people realized what it’s like.”

Since 1994 at least 7,000 human beings have lost their lives attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border, and thousands more have disappeared along the journey north. For example, the Pima County, Arizona Medical Examiner’s office counts 939 unidentified remains of border-crossers found between 2001 and 2016, while the Coalición de Derechos Humanos identifies more than 1,200 unresolved missing persons cases reported to the organization during 2015 alone. The harm inflicted by the death and disappearance of migrants extends to communities across the United States, Mexico, and Central America. As the Border Patrol deploys additional military tactics and technologies along the border like drones, Forward Operating Bases, and surveillance towers, and ramps up criminal prosecution and prison time for the crime of “unauthorized entry,” migrants are forced to cross ever-more dangerous terrain–leading to a spike in the death rate.

One of the key indicators written into the Border Patrol’s 1994 strategy document meant to measure the “success” of its deterrence strategy is the price that human smugglers charge to help people successfully enter the United States. This measure is premised on the belief that the more difficult the journey becomes, the more reliant migrants will be on organized smuggling groups, who will in turn increase their rates. Over the last two decades the cost of hiring a smuggler has indeed gone up. By 2012, researchers at the University of Arizona found that this cost had increased to an average of $2,400 per person. But this outcome has only made the border more chaotic, and more dangerous.

Indeed, as early as the late 1990s, organized criminal groups previously connected to the drug trade began to consolidate their control over the human smuggling industry, fueling violence and rendering migrants increasingly vulnerable to various forms of predation including extortion, assault, robbery, kidnapping, trafficking, torture, and murder. The scale of this violence is breathtaking, producing disruptions to everyday life in border areas and across Mexico, and driving new cycles of migration.

The role of the Border Patrol’s enforcement strategy in driving, rather than deterring, migration, is much more significant than frequently acknowledged. The increasing cost of migration has resulted in smuggling fees that are far beyond the income of most people in Mexico and Central America—especially those desperate to flee violence. This has led households to take on considerable debt to finance their journey. On the one hand, the resulting debt has a disciplinary effect on undocumented workers in the United States—who try to keep their heads down, work long hours, and accept workplace abuses in order to pay back this debt as quickly as possible. On the other hand, when an individual fails in their journey north—an outcome that the Border Patrol’s strategy of prevention through deterrence seeks to make increasingly likely—families risk losing homes, land and other essential resources used as collateral for their unpaid debts. Newly published research reveals that in order to avoid financial ruin, households may increase their chances of success by sending multiple family-members north, with the hope that at least one of them will make it across the border. Rather than being deterred, those who fail on their journey are just as likely to be incentivized to attempt crossing again as quickly as possible.

The Border Patrol’s Persistent Racism and Corruption

The Border Patrol’s contributions to organized crime and unauthorized migration are not only inadvertent or indirect. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) currently reports 168 cases of Customs and Border Protection agents who have been prosecuted for “mission compromising acts of corruption,” the highest-level corruption charge that includes active cooperation with smuggling cartels. These 168 cases only include those for whom sufficient evidence was gathered to indict and prosecute, and likely reflect only a fraction of the overall problem.

Indeed, in 2014, James Tomsheck, former assistant commissioner of the Border Patrol’s Office of Internal Affairs came forward as a whistleblower, claiming that by his estimation between 5 to 10% of the agency’s workforce are now or have been at one time been actively corrupt. The implications of this claim are staggering. On the one hand, it suggests a systemic failure of oversight and accountability, which would help to explain why acts of abuse and cruelty are so commonplace. On the other hand, when between 5 and 10% of the agency’s workforce is rotten, increasing the number of enforcement personnel, as Republicans are demanding, would likely have little impact on curtailing smuggling operations. Meanwhile, the militarization of border enforcement is doing tremendous damage to those U.S. communities where the agency’s operations concentrate. Nowhere is this clearer than in the use of racial profiling.

Consider for example the town of Arivaca, Arizona, situated about 12 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Arivaca is surrounded on all sides by semi-permanent Border Patrol checkpoints. In the course of any and all routine activities–driving to work, attending school, visiting a doctor or a grocery store–Arivaca residents must undergo inspection by federal agents and prove their citizenship or lawful status. After years of complaining about abusive treatment, a group of locals finally came together and petitioned the Border Patrol for information on how the checkpoints are used, whether and to what degree they are effective as intended, and whether Latinxs are disproportionately stopped and investigated–only to be told that the agency doesn’t track this information.

In 2013, Arivaca’s residents took things into their own hands, setting up a campaign to directly monitor checkpoint operations and record the patterns they observed. The results of this investigation were shocking: after documenting more than 2,379 separate vehicle stops, the checkpoint observers found that Latinxs were over 26 times more likely to be asked for their papers, and nearly 20 times as likely to be referred for secondary inspection as white, Anglo passengers and drivers. Adding insult to injury, not a single observed inspection resulted in arrest–meaning all of the drivers stopped and harassed were engaged in perfectly lawful activity.

Allegations of racial profiling are not limited to the United States’s southern border. In 2012 the American Immigration Council released a report revealing that Border Patrol agents in the state of Washington routinely monitored emergency 911 calls to identify Spanish-language speakers, and would then follow-up to investigate and detain these individuals. A 2011 report from the New York Civil Liberties Unions, meanwhile, documented systematic racial profiling by Border Patrol agents who board trains and buses along the U.S.-Canada border. The agency tracked those apprehended according to skin tone, with fully 84% recorded as being of “dark” or “medium” complexion. Agents, meanwhile, were offered gift cards to Macy’s and Home Depot as an incentive for reaching arrest quotas, resulting in hundreds of wrongful and trivial arrests.

Border Militarization is a Waste of Money

Since 1994 the annual budget for the U.S. Border Patrol has increased nine-fold, from $400 million to $3.8 billion dollars. Much of this funding has gone toward high-tech surveillance programs that the U.S. Government Accountability Office and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General agree are ill-suited to the Border Patrol’s mission and to the environment and terrain that its agents patrol, and therefore fail to perform as intended. Yet whether we consider the construction of a border “wall,” the Border Patrol’s Predator B drone program, or its quest for a high-tech virtual fence, the agency’s general practice has been to throw good money after bad–doubling down on enforcement programs regardless of their efficacy, while funneling billions of taxpayer dollars to defense and security contractors.

This pattern reflects a desire among agency brass to approach the border as a straightforward engineering problem—one that can be solved with the right mix of technology, infrastructure, and personnel. The problem, of course, is that most social problems are not engineering problems, while those in particular that drive human migration—violence, insecurity, family separation and economic inequality—cannot be meaningfully addressed, let alone resolved, by concentrating resources at the border. These social problems, rather, are spatially extensive, and require solutions that are responsive to particular local conditions.

An Alternative Proposal for the Borderlands

When launching his presidential campaign, Donald Trump famously disparaged immigrants from Mexico, suggesting “[T]hey're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people,” he said. Such flagrantly alarmist and misleading assertions are consistent with those continuously advanced by the Border Patrol and its agent’s union. For example, in late 2017 when two agents fell victim to an accident near Van Horne, Texas, the Border Patrol immediately blamed immigrants or drug smugglers, despite having no evidence to support this assertion. Even as the FBI and local investigators ruled out any kind of foul play, the agent’s union continued to spin this narrative, lashing out at the media and claiming their assertions were based on unique but unspecified insight. The Border Patrol’s claim that agents increasingly come under assault, therefore justifying the expansion of enforcement resources and authorities, is similarly dubious and unsupported by evidence –explaining why so few of these “assaults” are ever prosecuted.

Contrary to the lies circulated by the Border Patrol and its union, federal crime statistics reveal that border counties are among the safest in the United States. Instead, the forms of insecurity most pertinent to border communities are the same ones confronted across the country: poverty, racism, unemployment, outdated infrastructure, food insecurity, underfunded schools, unaffordable healthcare, unaffordable childcare, unchecked environmental pollution, and climate change.

Communities along the southern border, as elsewhere, could benefit from sustained federal investment around social issues that for too long have remained unaddressed. Rather than spending billions of federal dollars on walls, drones, and surveillance towers, why not invest this money in programs and infrastructure that will be of benefit to communities in the borderlands? At 21,370 agents, the Border Patrol itself already provides significant personnel who could be disarmed, retrained, and immediately put to work improving infrastructure, expanding Head Start and all-day kindergarten, providing meals to children and seniors, opening new centers for job training and adult education, advancing conservation and environmental restoration, and transitioning our country toward a clean energy future. Such efforts would certainly provide greater benefit and security for borderlands residents than the continued occupation of an armed, aggressive, and unaccountable federal police force.

The president’s continued lies and misrepresentation of borderlands and immigrant communities has taken us down a dark, toxic, and destructive path that is tearing at the fabric of the United States. The Border Patrol and its union have been among the chief champions of this agenda; for example, in 2016, the union broke with tradition and endorsed Trump early in the Republican primary cycle, boosting his candidacy and providing him legitimacy as a national leader. Trump and his allies in Congress have repaid the favor, attempting to funnel an almost unimaginable volume of money and resources into the hands of agents and the private security and defense contractors who support them (most recently, as a condition for continuing negotiations on the DREAM Act). Sooner or later the Trump era will come to an end, and we will have to find ways to begin to heal and reverse the tremendous harm his policies have unleashed. Turning a page on this era will require a decisive paradigm shift. We can begin by dismantling the Border Patrol.

Geoffrey Alan Boyce is a scholar and activist who lives in Tucson, Arizona. He writes and teaches on U.S. history, foreign policy and issues related to borders, migration and homeland security.