Over the last four years, a Spanish Netflix series called Money Heist (La Casa de Papel) has reportedly attracted the largest ever global viewership of any non-English-language series. The curious plot revolves around a meticulous bank robber—“the Professor”—who trains a group of criminal misfits to take over the Royal Mint of Spain, print up 2.4 billion euros over the course of 11 days, and make off with the money. Oddly, however, the scriptwriter’s incorporation of political themes into an apolitical genre makes for some inconsistencies in the plot that raise the question of whether the series was inspired by something other than a band of robbers.

After all, why would a non-ideological group of criminals run the enormous risks of taking over and defending buildings from Spain’s Guardia Civil national police force for weeks? Even more dumbfounding, in the second season, the robbers take over the Bank of Spain not to further enrich themselves, but to negotiate the freedom of their fellow robber “Rio,” who had been detained and was being tortured by Spanish authorities.

Why is the Spanish state so afraid of a band of robbers? And why would such robbers become a symbol of political resistance? The mix of bank heists and politics comes off as odd. The series’ incorporation of a human rights theme and its repopularization of the Italian antifascist hymn Bella Ciao seem out of place.

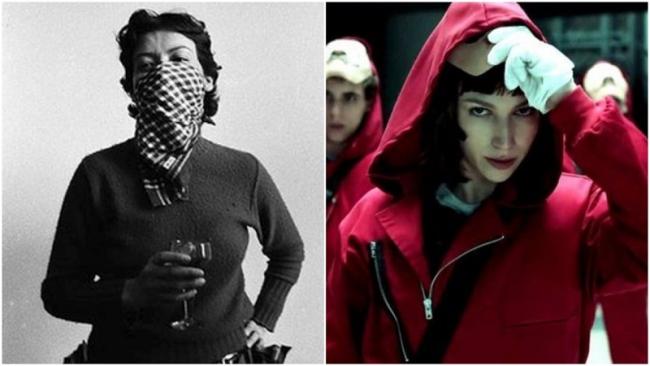

These oddities seem to derive from the near certainty that La Casa de Papel is at least partially inspired by an unorthodox Colombian guerrilla movement, the M-19, active from 1974 to 1990. As the Colombian intellectual Dario Hidalgo noted, the series’ two bank heists closely resemble two audacious M-19 operations in 1978 and 1980. In addition, the series’ robbers exhibit a number of tactics, attitudes, and role structures that are similar to those of the M-19’s early leadership.

The series’ scriptwriter, Álex Pina, admitted in an interview with the Colombian television channel RCN that Colombia has played an important role in his creative process. In the spring of 2020, he conceded that he wrote the last two episodes of the second season in Santa Marta, which is the birthplace of the M-19’s original leader, Jaime Bateman Cayón.

The Case: The M-19-Inspired La Casa De Papel

The first indication that La Casa de Papel is inspired by the M-19 comes early in the first episode, when the Professor seeks to impress upon his recruits the importance of training meticulously for the great heist. To convince them to spend months rehearsing the plan, he rhetorically asks: what’s five months if it means you and your children will never have to work again? Strangely, however, the Professor’s reasoning for all the preparation is conspicuously political. He insists that the group must avoid bloodshed so as to win over the public, warning that once blood is spilled, “We’ll stop being Robin Hoods and we’ll just become some sons of bitches.”

There are multiple layers of meaning in the Professor’s initial lecture. First, the scriptwriter seems to be taking a cue from the M-19’s legendary “Robin Hood” operations, in which its militants would commandeer trucks full of milk, food, and toys and give away the loot in Colombia’s poorest urban barrios. Without an M-19 inspiration, the Professor’s initial reference to Robin Hood would not be fully comprehensible, for there is no plan in the first season to give away any booty to the masses. It is not until the second season that the Professor finally orchestrates a spectacular M-19-style Robin Hood operation, dropping 140 million euros from a blimp on downtown Madrid.

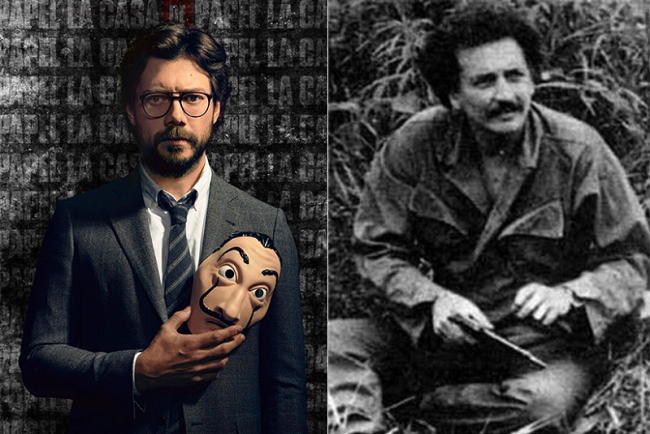

Second, in stressing the importance of winning over public opinion, the Professor slightly resembles Jaime Bateman, the original M-19 leader who died in a plane accident in 1983. Bateman was unique among Colombian guerrilla leaders in that he was highly attuned to popular symbols, values, and beliefs. Like the Professor, Bateman understood the popular appeal of audacious operations and Robin Hood-style actions in his time.

The Evidence: Extraordinary Coincidences with Two M-19 Operations

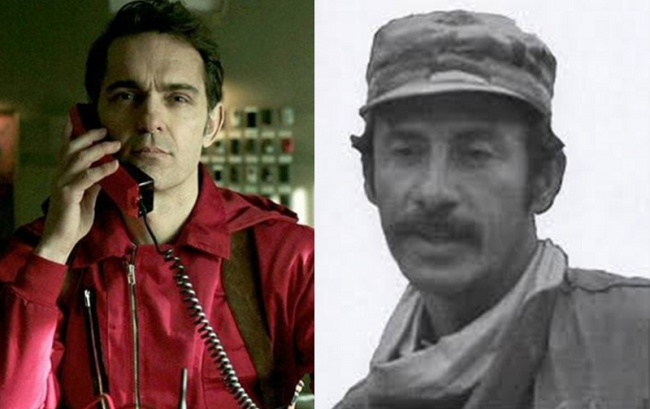

The first season’s heist of the Royal Mint would appear to be based on three parts of the M-19’s story: its robbery of 5,000 guns from Bogota’s Cantón Norte armory on December 31, 1978; the working relationship between Bateman and the M-19’s operatives; and the controversial figure of Iván Marino Ospina, the M-19’s second-in-command.

The most obvious coincidence between the heist of the Royal Mint and the M-19’s Cantón Norte robbery is that, in both cases, the robbers construct tunnels to make off with their loot. Moreover, the relationship between the Professor and his second-in-command “Berlin” has similarities to that between Bateman and Marino Ospina. Much like in the Professor and Berlin’s interactions in the first season, Bateman often gave the orders from a distance while Marino Ospina took part in operations. And like Berlin, Marino Ospina was a checkered figure. In early 1985, Marino Ospina was forced to cede leadership of the M-19 after being repudiated for having publicly applauded narcotraffickers’ threats against American diplomats living in Colombia. Marino Ospina then died on August 28, 1985, in the midst of a long firefight with Colombian authorities who had surrounded his Cali safehouse. Berlin’s twist of fate is conspicuously similar, as he also dishonors himself with acts of coldness and misogyny but then heroically sacrifices his life in a firefight with the Guardia Civil to help the group escape the Royal Mint.

The M-19’s apparent influence on the series becomes more obvious in the second season. At the beginning of the second season, Rio is captured in Panama and then taken by Spanish authorities to another country to be interrogated and tortured, much like M-19 leaders were apprehended and tortured by the Colombian state in the wake of the Cantón Norte robbery. After Rio’s capture, the Professor organizes the takeover of the Bank of Spain as a means of securing Rio’s freedom. This is the most far-fetched aspect of the series. The only way it makes sense that some nouveau-riche former robbers would go from lounging on Caribbean beaches to risking their lives again for the sake of Rio’s freedom is if we understand it to be modeled on the M-19’s takeover of Bogotá’s Dominican embassy in 1980.

The similarities are unmistakable. Much like the Professor, Bateman used the embassy takeover to highlight the torture of jailed M-19 leaders and to pursue their release in exchange for hostages. Just as the Professor introduces himself to the Spanish people on a Madrid jumbotron in the second season, Bateman gave his first public interview to the Bogotá-based newspaper El Siglo during the 1980 embassy takeover. And much like the Professor uses public support for his group and media scrutiny of the state’s human rights abuses as bargaining chips in his negotiations with Spanish officials, Bateman used public sympathy for the M-19 and international criticism of the Colombian government’s human rights record to apply pressure on the Colombian state to negotiate with him.

Beyond La Casa de Papel: Bateman’s More Enduring Lessons

Assuming that La Casa de Papel is inspired by the story of the M-19, where might such an inspiration lead us? What lessons can we glean from Bateman’s vision and the experiences of the M-19 that have value for people today?

First, we should caution people against nostalgia for an earlier era of political violence and audacious armed operations. For Bateman, armed struggle was never an end in and of itself, but rather a means to an end. Moreover, in the closing years of his life, he recognized the immense costs of political violence and was in the process of seeking peace.

Along that vein, we might consider shifting the discussion more toward those insights of Bateman that La Casa de Papel leaves out. In my view, Bateman’s most important and timeless insights lie not in his ideas about armed struggle but in his ideas about nation-building. Bateman recognized a powerful cultural yearning for a national identity that was inclusive of Colombians of all social positions and ethnicities. His conception of the “sancocho nacional” was rooted in a vision of democracy in which all sectors of society would have a seat at the table. He sought the development of a common understanding of the nation’s social problems through a national dialogue between different economic sectors and popular movements. For Bateman, such a dialogue was key to tackling the nation’s social problems and achieving peace.

Naturally, an inclusive and pluralistic national identity would never require all a nation’s citizens to adopt the same vision of how to tackle its problems. Rather, what Bateman sought to impress upon us was that, in order for a society to be capable of addressing social problems, it must open the channels for dialogue necessary to develop some common understandings of what its most pressing problems are. In that sense, Bateman’s lessons about nation-building in the Americas are as poignant today as they were at the time of his death in 1983.

Justin Delacour is an Assistant Professor of political science at Lewis University in Romeoville, Illinois. He specializes in Latin American politics and U.S.-Latin American relations. He can be contacted at delacoju@lewisu.edu.