Facing a critical moment for his center-right government, President Sebastián Piñera appears to be taking inspiration from Plato. Worried about the harmful effects of the dramatic arts in fifth-century Athens, the Greek philosopher famously banned the poets from his ideal city, the “Republic.” Poetry, Plato wrote, “feeds and waters the passions.”

The Chilean state clearly fears the power of art to ignite the passions in its republic today. The state is still struggling for control of Santiago after a year of social unrest, and a historic national referendum on October 25 will determine the fate of the 1980 Constitution.

Since the outbreak of the social uprising (estallido social) on October 18, 2019, the government has undertaken a series of measures to limit the reach of public art and protest. In November 2019, the Carabineros de Chile (the national police force) threatened to take civic and legal action against the popular Chilean singer-songwriter Mon Laferte for suggesting the police were behind the fire bombings of the metro that ignited the social revolution. More recently, the police have brought legal charges against the four founders of Las Tesis, the performance collective that created “A Rapist in Your Path” (Un violador en tu camino), the flash mob dance that became a global feminist anthem in the fall of 2019. Two laws aiming to preserve public order, an “anti-looting” law and an “anti-barricade” law, were passed in January 2020, and other laws are currently under debate.

The limits of public art and political expression are at stake in Chile today. Through the legal system and direct challenges to expression, the Chilean state is restricting the bounds of what is allowed in the public sphere.

Art and the Estallido Social

Chileans have long drawn on the arts for protest, and the social explosion that erupted in October 2019 was no exception. While the uprising was triggered by a minor subway fare hike, it soon become a full-fledged revolt against the neoliberal principles and culture of impunity that derive from the legacy of the brutal 17-year regime of Augusto Pinochet. Citizens from all walks of life took to their balconies and the streets with pots and pans, drawing on the popular tradition of the cacerolazo to express their frustration with rising social inequality and inadequate systems of education, health care, and social security.

Support for the social revolution came from a cross-section of the arts, and Plaza Dignidad, as Plaza Italia was renamed in line with the central protest principle of dignity, became its cultural epicenter. The equestrian statue of nineteenth-century General Baquedano was covered in a rash of graffiti and Mapuche flags, and three wooden statues honoring Indigenous peoples were installed in the plaza.

Performance artists added their voices to the artistic explosion of the city. On October 25, scores of musicians gathered in front of the National Library for “1,000 Guitars for Víctor Jara,” a massive tribute to the legendary folk singer who was tortured and murdered by the Pinochet regime and who quickly became an iconic figure in the protest movement. Mon Laferte bared her breasts at the Latin Grammy Awards on November 14, 2019, revealing the words, “In Chile, They Torture, Rape and Kill,” on her chest. On March 6, 2020, Chilean folk singer Nano Stern performed the song, “I Gave Away My Eyes,” at Plaza Dignidad, an homage to Gustavo Gatica, a 21-year old psychology student who had been blinded by police buckshot while taking photos at a peaceful demonstration.

Since the 2019 social uprising, Chileans have been breaking down the walls between public and institutionalized art. The cultural landscape has witnessed the birth of new artistic bodies, such as the Museo de la Dignidad, an open-air museum which sought to preserve the ethos of the social revolution by framing street art advocating “dignity”; the Museo del Estallido Social, a “Museum of the People and For the People”; and Radio Plaza de la Dignidad, the “radio station of the revolt.” A highly visible poster of martyred Mapuche activist Camilo Catrillanca by the Colectivo de Serigrafía Instantánea has been selected for exhibition in the current Berlin Biennale.

Criminalizing Public Art and Protest

Authorities did not wait long to crack down on artistic forms of protest. In addition to the public order laws, two other laws are wending their way through congress: an “anti-hooding” law and a “sticker law,” which imposes serious penalties for the defacement of public transportation and related infrastructure with public art, including “messages, signatures, lines, drawings or other figures or expressions, writings, inscriptions or graphics.”

Following the threats against Mon Laferte for defamation, the police have brought two charges against Las Tesis: incitement to violence and contempt for authority. An official complaint, supported by the Chilean Minister of the Interior, was filed on June 12. The complaint holds the group responsible for inciting violence against the police in a video with inflammatory language and for provoking “serious incidents of disturbance of public order” in the larger context of the social protests.

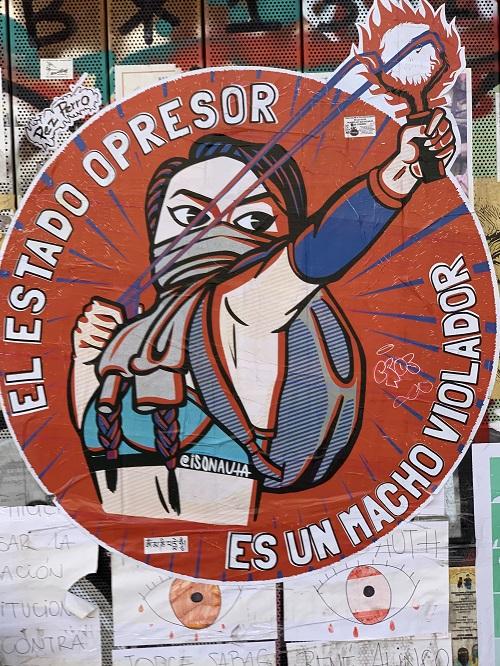

The campaign against Las Tesis is one of the most egregious examples of artistic censure. By enacting “theses” of seminal feminist theorists via coordinated and choreographed performances, Las Tesis seeks to raise awareness of institutional violence against women and dissidents. While Chile has made some inroads toward gender equity in the past decade, gender-based violence is still prevalent. The Chilean Network Against Violence Towards Women reports 4,113 cases of rape and 13,837 counts of sexual abuse in 2019. During the 2019-20 social uprising, women were subject to various forms of police brutality, including violence, sexual assault, and degrading treatment, such as forced denuding and squatting for cavity checks, a practice which was banned in March 2019.

In the Chilean tradition of funa, a staged, public accusation for an unprosecuted crime, “A Rapist in Your Path” “calls out” the institutionalized violence of the patriarchal state. In the fall of 2019, the flash mob dance was performed at strategic locales across Chile, including the notorious National Stadium, where a performance of “Las Tesis Senior” on December 4 drew more than 10,000 women over 40 years of age. The accusatory stance taken by thousands of activists was rendered in powerful protest graphics, such as Loreto (Lolo) Góngora's paste-up at the Gabriel Mistral Cultural Center (GAM), in which a fierce, female figure points directly at the viewer: “THE RAPIST IS YOU!”

“A Rapist in Your Path” has been one of the most effective feminist campaigns in recent decades to raise awareness of gender-based violence. The rapid-fire spread of the rape protest song is a testament to its significance. According to Mireya Leyton, one of the founders of “Las Tesis Senior,” the eight women who organized the performance at the National Stadium were stunned by the speed with which their call traveled across social media. “We set up WhatsApp groups, and in less than one day, we had 11 WhatsApp groups with more than 3,500 women who wanted to make more groups,” Leyton said in an interview. “Then we were overwhelmed. We asked for help, and we asked our friends for help.”

As numerous feminists have pointed out, the reason for the song’s global appeal is the ubiquitous nature of gender-based violence. “It is a very short piece that sums up centuries of abuse,” Leyton explained. “What ‘A Rapist in Your Path’ does is universalize a form of protest.” According to Leyton, the flash mob dance is a form of non-violent protest which served to sublimate passions (contra Plato) and to temper the violence in Chile (contra the Chilean police).

“[It] is a very angry, but peaceful protest. What is really interesting is that when ‘A Rapist in Your Path’ came to the protests in Chile, we witnessed a drop in violence in the protests. The thing about women is ‘I'm angry, but I don't have to burn a bus,’” she said.

Numerous human rights bodies have voiced opposition to the charges against Las Tesis. The Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights affirmed “the need to guarantee women's right to freedom of expression … as a tool to combat gender-based violence” and cautioned against criminalizing expression–no matter how offensive or shocking the subject matter–that falls into the domain of “matters of public interest.” Other groups to speak out against the charges are PEN Chile and PEN International, a collective of 150 Latin American artists, writers, and cultural critics, and a group of Hollywood actors and activists.

“The group and the song have become a symbol of the universal demand of women to be able to live a life free of violence,” declared the UN Working Group on Discrimination Against Women and Girls. “We fear prosecution of Las Tesis could have a chilling effect on women in many other countries who are standing up for their human rights.”

State Control During the Pandemic

The Chilean state was unable to gain control of the capital until the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, which hit the country hard. On March 18, 2020, five months to the day from the start of the protests, President Piñera declared a 90-day “state of catastrophe.” Within hours of the government’s decree, a professional clean-up crew arrived at Plaza Dignidad. While the police stood guard, and the citizens slept, they sprayed down the square and the statue of General Baquedano with water jets, removed the three Indigenous statues, and painted over the protest graphics that covered the walls of the main avenues.

Visual artist Lolo Góngora, who created several signature feminist graphics during the estallido, was critical of the government’s instrumentalization of the pandemic. “So you see the government’s censorship,” she said in an interview. “They are more concerned with erasing the testimony of social unrest, of social discontent, than buying masks and giving supplies to hospitals.”

Painter and gallery owner Paloma Rodríguez, whose pop-inflected paste-ups added a playful edge to the protest graphics, similarly found the government’s priorities misguided. “[T]o erase all the dissident art on the walls, they waste water and money while people are starving in our country,” she noted in an interview. “Almost none of the physical works that were created during the social uprising remain.”

Despite a period of relative quiet, in which the social revolution took more underground and virtual forms, the “barricades” are once again in play, and the statue of General Baquedano has become its symbolic center. On Friday, October 16, almost one year from the start of the uprising, “Ground Zero” was occupied by protestors, and the statue and pedestal were covered in red paint (a marker of blood spilled in the uprising), only to be restored by the authorities during the early hours of the nighttime curfew.

The Chilean state’s attempt to limit the reach of public art and to censor the free expression of artists and performers is at the same time an attempt to maintain clear borders between “acceptable” and “non-acceptable” art. These actions have dangerous historical antecedents.

What is animating the performances of Las Tesis and other social collectives in Chile is a sense of justice. The impunity baked into the Chilean system has led Chileans to turn to “people power” to bring about structural change.

Outrage has a place in democratic society. When the legal system fails, intense artistic expression provides a measure of social and political harms. Recent global developments, such as the harsh crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and the violent clashes between Black Lives Matter demonstrators and police in Portland, Oregon and other U.S. cities, suggest that the power to protest is in peril. If the Chilean national police force successfully prosecutes Las Tesis for calling out the state and threatening the vertical, neoliberal model that enables it to function, it will set a dangerous precedent for public art and expression, not only in Chile but across the globe.

Terri Gordon-Zolov is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at The New School in New York City. She is co-author with Eric Zolov of The Walls of Santiago: Social Revolution and Political Aesthetics in Contemporary Chile, a book on the protest graphics in Chile’s 2019-20 social revolution (forthcoming by Berghahn Books).