As a child, I often spent weekends with my grandmother. In addition to showing me how to cook Puerto Rican food, she would occasionally reminisce about her childhood. She told me about the journey she made with her parents from Cayey in the mountains of Puerto Rico to the farms of Florida, then on to New Jersey, where she spent most of her childhood. She recounted the trials and tribulations of growing up as the daughter of migrant farmworkers in New Jersey and her own incorporation into the working class through factory work. It was these stories that instilled in me a lifelong interest in the connections between government policy, land, and labor in Latin America.

My grandmother flew to the United States with her mother in 1950, the same year that members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party raised the Puerto Rican flag over the small mountain town of Jayuya and tried assassinating President Harry Truman in Washington. She, like many Puerto Ricans of her generation, was part of Operation Bootstrap, a neo-Malthusian model of industrialization that exported workers from rural Puerto Rico to serve as a cheap source of labor for U.S. businesses. Yet, despite the historical significance of Puerto Rican migrant farmworkers, much of the literature on Puerto Rican migration has focused on Puerto Ricans who migrated to industrial cities like New York and Chicago.

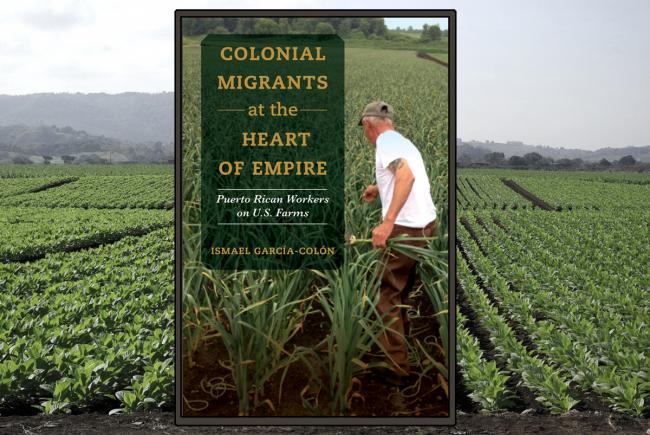

Ismael García-Colón's Colonial Migrants at the Heart of Empire: Puerto Rican Workers on U.S. Farms fills this gap in literature by providing a comprehensive history of Puerto Rican farm labor migration. Colonial Migrants connects Puerto Rican migration to the rural United States with the larger themes of Puerto Rico's colonial relation to the United States, the modernization project of Governor Luis Muñoz Marín's Popular Democratic Party (PPD), and the formation of a Puerto Rican ethnic group in the United States. Using decades of ethnographic work among Puerto Rican farmworkers in the northeastern United States, García-Colón weaves these three concepts together into an exciting read for anyone interested in Puerto Rican or Latinx history.

Colonial Migrants begins by examining the history of Puerto Rico's colonial relationship to the United States in the years following the North American invasion of 1898. The ambiguity surrounding Puerto Ricans’ citizenship defined these early years, when Puerto Ricans were seen as "foreign in a domestic sense." It was okay for Puerto Ricans to go to far off places like Hawaii or the Panamá Canal, but their tenuous citizenship status worked against them in two ways: they were not considered white enough for “respectable” employment, nor easily deportable if necessary, like immigrant labor. Eventually it was this colonial ambiguity that allowed Puerto Ricans to benefit from their rights as U.S. citizens, and take advantage of federal laws that required employers to show that they could not fill farm labor positions with U.S. citizens.

During the 16 years that Puerto Rico's first elected governor Luis Muñoz Marín was in power, this ambiguity was institutionalized in the form of Puerto Rico's territorial status as un estado libre asociado (ELA) in 1952. The term is officially translated as commonwealth, but the literal translation of “associated free state” better communicates Muñoz Marín's postcolonial intentions.

The ELA sought to turn Puerto Rico from a primarily agricultural society into a modern industrialized showcase of capitalism, a showcase that would serve as an example for the rest of the region. But there was one problem for Puerto Rico's political elites: there were too many people on the island to make their project work. This perceived "overpopulation" led the Puerto Rican government to encourage unemployed or underemployed workers and jíbaros (subsistence farmers) to migrate to the United States where North American employers needed their labor. Colonial Migrants tells the story of how the Puerto Rican government's Farm Labor Program (FLP) spurred a wave of migration the rural northeast and midwest to work in agriculture, an industry often dominated by immigrant labor.

Through research on the Farm Labor Program, Colonial Migrants highlights both the balancing act that the Puerto Rican government played, marketing their citizens as a cheap source of domestic labor while also trying to ensure that Puerto Rican farm workers were treated with dignity and their rights respected by employers. To do so, Puerto Rican officials set up regional offices to receive migrants, connect directly with employers, lobby the national and state governments, and inspect the farms where migrants worked and lived.

While the Farm Labor Program and Puerto Rican government were key in spurring migration, García-Colón dedicates much of the book to showing that migrants were active participants in carving out their future in the United States. He shows that workers often defined the terms of their labor by migrating without official Puerto Rican government contracts, leaving jobs where they were treated unfairly, and settling into rural communities that were initially hostile to the presence of "foreigners."

In these rural communities, food offered workers an opportunity to take agency over their lives. According to García-Colón, Puerto Rican workers often found it difficult to adapt to the tasteless (and sometimes unsanitary) food they were served in the labor camps, and many were disappointed when they didn't receive rice and beans with their meals. However, this presented an opportunity for Puerto Rican entrepreneurs to sell food that quelled the workers’ homesickness.

Like today, the Puerto Rican experience at the height of the Farm Labor Program was marred with racism, but workers actively organized against racism and for their rights at the workplace. The most vivid example mentioned in Colonial Migrants took place in 1966 in upstate New York when police beat and intimidated two Puerto rican workers over a traffic stop. In response, dozens of workers took to the streets in North Collins, a town with a population of 1,000. Their efforts led to the New York state and Puerto Rican governments raising awareness about the blatant racism that migrant workers experienced in the rural northeast.

The beginning of the end of the Farm Labor Program came, much like the rest of the muñocista development policies, when the pro-statehood New Progressive Party (PNP) came to power with the election of Luis E. Ferré in 1969. While there were efforts to repair it under subsequent PPD governments, the economic winds pushed both parties in Puerto Rico towards neoliberalism and made employers in the United States less likely to seek out Puerto Rican workers.

Despite the fact that Puerto Rican farm laborers have shrunk to very small numbers, Colonial Migrants remains relevant to understanding the decline of the Estado Libre Asociado, the Puerto Rican diaspora, and the issues that Latinos face in the rural United States. García-Colón’s fantastic storytelling makes this history of Puerto Ricans, like my grandmother, who migrated to farms across the United States accessible to new generations.

Cruz Bonlarron Martínez is an independent writer and researcher. He's currently conducting a Fulbright research fellowship on the connection between agrarian reform and the peace process in Antioquia, Colombia.