On November 8, 2024, 70-year-old Mapuche elder Julia Chuñil, accompanied by her dog Cholito, left her home to check on her cows. They never returned home. Before she vanished without a trace into Chile’s Araucanian wilderness, the Mapuche community leader and land defender had reportedly left a warning with her relatives: “If I do not return, you know who did this.”

The mysterious disappearance of Chuñil is the latest incident in the so-called “Mapuche conflict” in Chile’s Southern Araucanian region, where Indigenous people are locked into a fight for survival with forestry companies that exploit the area’s rich natural resources. Despite President Gabriel Boric’s vow to mend relations with the country’s Indigenous peoples upon taking power in 2022, relations between the Mapuche and the so-called progressive state remain fraught.

The Mapuche traditionally hail from a region that encompasses what we now recognize as Chile and Argentina. Their territory on the Chilean side of the border is called Wallmapu. The Mapuche are the largest ethnic group in Chile, making up around 12 percent of the population, but their language, Mapudugun, and way of life have been badly hurt by centuries of repression and eviction from their ancestral lands. The Mapuche have never been fully subjugated, successfully resisting dispossession from their lands since the arrival of Spanish colonizers in 1536.

Today the primary cause of conflict between Chile’s Mapuche communities and the government is the rapid expansion of extractive forestry companies that have occupied and irreversibly destroyed ancient forests. These companies, linked to the Chilean government’s extractivist agenda, have added fuel to a longstanding conflict between the state and the Mapuche community that no government has yet been able to solve. As the case of Chuñil reveals, the state’s inability to resolve—or direct complicity in—these land conflicts has been deadly.

Corporate Interests and Abusive Landowners

Chuñil’s family have placed some of the blame for her disappearance on the National Corporation for Indigenous Development (CONADI), a government agency that was set up in 1993. Though it is tasked with protecting and promoting the rights and culture of Indigenous peoples, is has been criticized from its inception.

Indigenous communities have accused CONADI of favoring the interests of land owners and corporate industries over the wellbeing of the people it claims to serve. In 2011, two Mapuche CONADI board members vetoed a hydropower project on Mapuche land. In response, they were removed from the agency's board which has since consisted solely of non-Indigenous members, clearing obstacles to enable the dam project to proceed.

In the case of Chuñil, community members allege that CONADI acquired the contested piece of land, known as Fundo Lafrir, with the goal of transferring it to the Blanca Lepin community in nearby Lautaro. When they rejected the offer, the land was left in legal limbo, where it remains today. Amid the dispute, Chuñil, a well-respected community elder, took custody of the land to preserve the native forest. According to her family, the confusion that CONADI created over the legal status of the forest led to an escalation of the dispute and threats of violence against Chuñil.

According to Jeanette Trocoso Chuñil, Julia Chuñil's daughter, land law is pitted against Indigenous communities and favors actors such as Juan Carlos Morstand Andwandter, a local landowner who allegedly threatened Chuñil in the months leading up to her disappearance. Shortly before her disappearance, Morstand presented a judicial case trying to evict Chuñil from her land after she resisted selling it to him.

The conflict between the Mapuche community and Juan Carlos Morstand Andwandter has deep roots. Morstand Andwandter comes from a family with a long history of landownership—and exploitation—in the region. His grandfather was a landowner, local judge, and abusive boss, according to a 1935 local newspaper clipping titled “The Latifundistas Continue Their Abuses” that describes the ill treatment and exploitation of the workers on his land. The family also maintains connections to local law enforcement.

Drawing on this history, Indigenous activists made clear that this case was about more than Chuñil. “This is not just a problem for our mother, it’s for the whole community struggling to recover its rights and territory,” Troncoso Chuñil told Werken, an independent media outlet. Her mother’s disappearance is, she claims, “an attempt to silence the Mapuche struggle.”

Aggressive Forestry Expansion

The disappearance of Chuñil is the latest in a series of incidents in which Mapuche elders and activists have been killed in confrontations with the forestry sector, an industry that has developed increasingly close ties to the Chilean state in recent decades.

The relationship between the government and the forestry sector rapidly accelerated during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The regime targeted forestry as a key sector of development and implemented policies that favored the expansion of large tree plantations. In the pursuit of a neoliberal economic model, state-owned forested lands were privatized, sold to large corporations at low costs, and converted into industrial plantations. The regime also weakened labor protections, making it easier for forestry companies to hire underpaid workers, and gave the National Forestry Corporation control over Mapuche lands. These reforms set in motion the rapid expansion of forestry companies on lands traditionally occupied by the Mapuche people, leading to the environmental destruction of the region and the displacement of Indigenous communities.

Chile's native forests have experienced significant reductions in the last 40 years. Between 1985 and 1995, nearly 2 million hectares of native forests were lost due to their conversion into industrial tree plantations. Today, Chile hosts the world's largest expanse of radiata pine plantations. As a result, half of the country’s 15.4 million hectares of forests are degraded and some of its native forests are among the world's most endangered. The forestry industry’s disproportionate consumption of Chile’s freshwater resources, as well the proliferation of highly flammable species like eucalyptus on monoculture plantations, have been linked to the spread of deadly wildfires, including the 2023 wildfires in central and southern Chile.

By the 1990s, forestry companies owned approximately three times more ancestral Mapuche land than the Mapuche people themselves. In the context of aggressive expansion, forestry companies such as Mininco and Arauco have been directly implicated in human rights abuses against the Mapuche people that include land expropriation, environmental degradation, threats of violence, and collaboration with state forces leading to the criminalization of Mapuche land defenders.

False Promises of Dialogue

President Gabriel Boric came to power in a context of heightened conflict in the Araucanía region, after his predecessor Sebastián Piñera oversaw a period of repression and violence that led to multiple deaths. In June 2020, Alejandro Treuquil, a spokesperson for the We Newén community, was assassinated in Collipulli, in Chile’s Araucanía region. According to his wife, Andrea Neculpán, the police began harassing them prior to his death, with one officer threatening to kill Treuquil. On July 9, 2021, Pablo Marchant, a Mapuche activist, was shot and killed by Chilean police during a confrontation with the Mininco forestry company. The incident occurred while Marchant, along with members of the militant Mapuche organization Coordinadora Arauco Malleco (CAM), were asserting territorial rights on disputed land that was occupied by Mininco. In November 2021, 23-year old Yordan Llempi Machacan was killed and three others were injured when Marine Luis Felipe Videla and Corporal Richard Seguel opened fire on a group of demonstrators.

Despite Boric’s pledges to end the conflict between the Chilean state and Indigenous peoples, repression against the Mapuche has continued under his “progressive” government. During his campaign, Boric had promised to pursue a “path of dialogue” which would “annoy those who believe that things can be achieved through violence or confrontation,” but in practice military spending in the region has continued to increase. In May 2022, the Boric government authorized the deployment of the military to Araucanía. This decision marked a clear continuation of the militarization policies initiated by previous repressive administrations. The government increased its spending by $1.5 billion in 2023 and provided the police with expensive, highly specialized drones intended for surveillance in Araucanía.

The state has also targeted the Mapuche in other ways. In 2022, the Chamber of Deputies declared the CAM an “illicit terrorist organization.” The same year, police arrested its leader, renowned anti-capitalist spokesman Hector Llaitul, and several other CAM members, including his son Ernesto, for arson attacks and other activities associated with territorial defense. Following his 2024 sentencing to 23 years in prison on charges including incitement to violence, firearms use, and timber theft, Llaitul and other Mapuche political prisoners engaged in hunger strikes to protest their imprisonment and the treatment of Indigenous activists in Chile.

Activists see echoes of the state’s violent treatment of Indigenous activists in the case of Chuñil’s disappearance. “The case of Julia Chuñil not only exposes the territorial conflict,” said Richard Curinao, a Mapuche activist and editor of Werken News, “but also the responsibility of the state that continues to deepen structural violence against the Mapuche people.”

“The Silence of the State Kills”

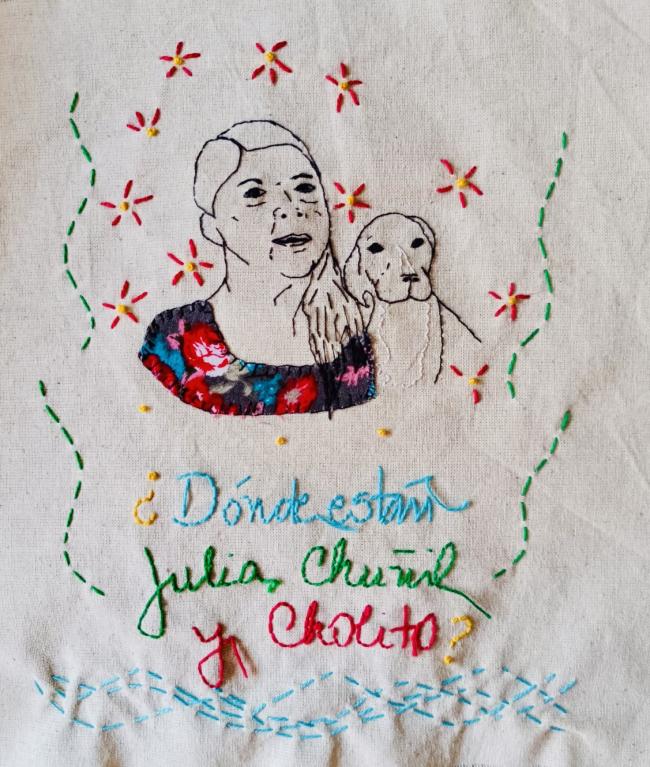

On January 8, protesters gathered outside La Moneda in Santiago. They held up placards that read, “¿Dondé están Julia Chuñil y Cholito?”, “El Silencio del Estado Mata,” (the silence of the state kills), and “Sabemos quienes fueron” (We know who it was). The protest was supported by local human rights groups as well as Chuñil’s son, Pablo San Martin Chuñil, who traveled to the capital accompanied by local and international Mapuche groups. At the protest, he called upon the Chilean government to prosecute those responsible for the disappearance of his mother.

Despite calls from Indigenous and environmental activists for a more thorough investigation, Chuñil’s whereabouts remain unknown. The fact that a prominent community leader can be disappeared under a progressive government sends a chilling message about the power of landowners who will stop at nothing to achieve their commercial aims. Despite the creation of agencies such as CONADI and false promises of dialogue, it is evident that the Mapuche people in Chile remain as unprotected and neglected as the native forests they struggle to preserve.

Carole Concha Bell is a PhD candidate at King's College London. She is researching Chilean second-generation diaspora literature and regime discourse at the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures (DLLC). She is also a regular contributor to national and international media on the subject of Chilean politics and Indigenous rights.

Editor's note: This article was updated on January 30, 2025 to accurately reflect the year that Gabriel Boric was elected.