Co-published with Intervenxiones of the Latinx Project.

Last year marked 50 years since the founding El Comité-MINP (Movimiento de Izquierda Nacional Puertorriqueño), a radical socialist movement that would last throughout the 1970s and into the early part of the 1980s. Former members held a virtual commemoration hosted by the People’s Forum, which included panels, performances, and presentations, as well as a screening of Rompiendo Puertas (Break and Enter) a 1971 documentary produced by Third World Newsreel that focuses on Operation Move-In and the early housing reclamation movement in New York City.

The film portrays low-income families on the Upper West Side of Manhattan facing eviction under the guise of urban renewal. In response, Operation Move-In, a two-year movement involving direct actions to reclaim vacant housing stock, began in the summer of 1970 and eventually grew to include many buildings and over 200 families. The founding members of El Comité quickly joined this grassroots struggle, holding meetings in an empty storefront on 88th St. and Columbus Avenue, and publishing a biweekly newspaper called Unidad Latina.

Led “predominantly by working-class Puerto Rican activists” from Manhattan’s West Side, El Comité developed organically—from an informal collective to a sophisticated Marxist-Leninist cadre organization with chapters in neighborhoods around New York City, on college campuses, and beyond (Muzio 40). Some of their signature achievements include the first successful district-wide campaign for bilingual education; legitimacy for gypsy cab drivers who went to pick up passengers where yellow cabs would not; a Latin Women’s collective; protests of PBS which resulted in the show Realidades, a weekly television series on Latino life that lasted three years; co-hosting the first-ever conference on Puerto Rican political prisoners, which was organized with The Young Lords and the Puerto Rican Student Union at Columbia University; advocating for community control in education; and organizing a coalition of African-American and Puerto Rican construction workers for access to construction jobs in the Bronx.

Even so, there is a dearth of literature on the history of El Comité, which was only recently addressed in the groundbreaking 2017 book, Radical Imagination, Radical Humanity: Puerto Rican Political Activism in New York (SUNY Press), written by former member and SUNY Old Westbury professor Rose Muzio. As the first book-length critical study on El Comité, Radical Imagination, Radical Humanity not only offers a nuanced portrait of the group’s history, but also provides insight into its unique origins and rapid evolution.

El Comité was not formed with a revolutionary ethos or political ideology, like say, the New York chapter of the Young Lords. Some members were slightly older, first or second generation Puerto Ricans, Vietnam veterans, unemployed laborers, factory workers, etc. Others had young families, while most had virtually no experience with community organizing and only limited experience with radical politics. Muzio, however, attributes a somewhat latent political consciousness to some of the founding members as a consequence of the radical social milieu of the era and the familial ties of some members of El Comité to the Nationalist Party’s movement for independence in Puerto Rico.

To illustrate this point, Muzio traces the origins of El Comité to the so-called “ice cream action,” which took place around the same time Operation Move-In was underway in the summer of 1970. As founding member Pedro Rentas tells in the book, a group of approximately 20 men went to a sandlot in Central Park to play baseball on a hot summer day in June. Afterwards, they solicited donations from neighbors to buy beer, unexpectedly collecting almost $100, which was then spent on ice cream for the children in the neighborhood. The following week, this collective of mostly Vietnam veterans, factory workers, and unemployed laborers were inspired to not only repeat this kind act, but to also host an outdoor movie screening of Planet of the Apes.

At the time, the Upper West Side was a working class, densely populated neighborhood, racially and ethnically diverse (Muzio 17), yet plagued with territorial gang violence. The film screenings, according to Rentas, “provided not only free entertainment, but an opportunity for people to gather on neutral ground.” This commitment to activism rooted in the community is an enduring component of El Comité’s legacy and reinforces the immediate perception of its members in the aftermath of Operation Move-In as “a principled group, with no hidden agenda or desire for acclaim, independent of elected leaders and anti-poverty agencies that bought into institutional politics and compromised community interests” (Muzio, 40).

Muzio also argues that this brand of grassroots activism counters the misconception that radical organizations of the Puerto Rican Left were primarily concerned with the struggle for Puerto Rican independence and not the material conditions of Puerto Ricans living in the diaspora. By 1973, El Comité began an internal process of reorganization. Despite a lack of formal education among the founders of El Comité, the group sought to educate itself politically, continuing a process of organic growth of their ideological platform. Two years later, they officially changed their name to El Comité-MINP and emerged as a Marxist-Leninist cadre organization, with Unidad Latina becoming Obreros en Marcha. Muzio describes the name change:

“‘Puerto Rican’ in the name signified the organization’s focus on Puerto Rican communities; ‘National Movement’ intended to convey the idea that the movement for socialism was ultimately national, not local.” (Muzio, 56)

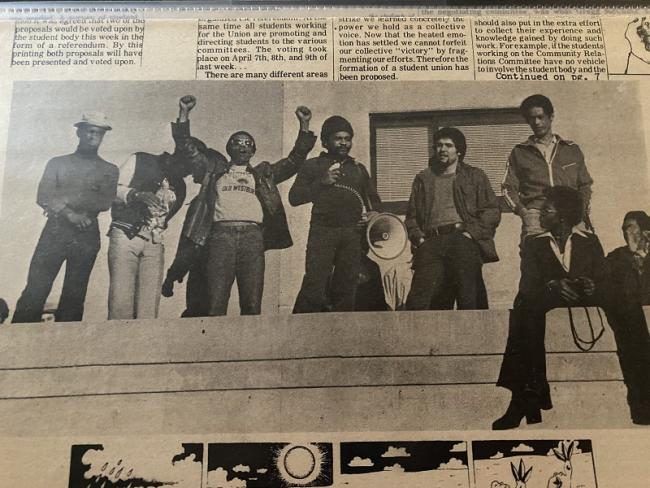

The group also expanded throughout the city by adding new chapters. Yet while their new goals included forming a national network among radical socialist movements, El Comité had extended its reach throughout New York City. In the South Bronx, they protested urban decay. In East Harlem, they fought to keep Metropolitan Hospital open. And in the Lower East Side, they launched a campaign to protect city funding for daycare. El Comité was also active on college campuses. The Frente Estudiantil Puertorriqueño led student protests at SUNY College at Old Westbury on Long Island from 1976-77, and in the process, helped to preserve a legacy of multiculturalism and egalitarianism enshrined in the mission statement of the school. El Comité-MINP also broadened its solidarity efforts by joining the Vieques Support Network’s New York Committee in 1978.

Around this time, several founding members, including First Secretary Federico Lora, would also relocate to Puerto Rico, which was an important factor in the organization’s slow decline in the years that followed. Ultimately, El Comité had a split in its membership in 1981. An ethos of ‘democratic centralism,’ which had been key to the organization’s success, would also play a role in its downfall. Whether or not to formally enter politics or whether to remain strictly an activist organization was among several issues that led to this fracturing. By 1984, the group formally disbanded, although members would go on to participate in struggles such as the labor movement in Puerto Rico and later, the Vieques Movement to remove the U.S. Navy from conducting bomb tests there.

It is noteworthy that El Comité remained active much longer than most leftist organizations of the era, especially given the deep economic recession and state repression. They were, for example, able to avoid surveillance and infiltration through careful vetting of potential recruits and maintaining strict lines of communication within the organization. While not as celebrated as the Young Lords, their crosstown counterparts, the group nonetheless made lasting contributions as part of the Puerto Rican Left, the Third World Left, and various grassroots political movements in New York City.

Watch the 50th anniversary event on YouTube.

Néstor David Pastor is a writer, musician, and translator from Queens, NY. Currently, he works with NACLA as Outreach Coordinator/Editorial Assistant and with the Latinx Project at NYU as managing editor of the digital publication Intervenxions He is also the founder of Huellas, a forthcoming bilingual magazine of long form narrative non-fiction. Follow him @ni_soy_pastor.