This piece appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today or order an individual copy of this issue here!

How do we even begin

to open our mouths

when all we can do

is scream

only to be met

with deafening silence

– Leslieann Hobayan, “Scattered”

When this is over there is no over but quiet.

Coworkers will congratulate me on the ceasefire

and I will stretch my teeth into a country.

As though I don’t take Al Jazeera to the bath.

As though I don’t pray in broken Arabic.

It’s okay. They like me. They like me in a museum.

– Hala Alyan, “Naturalized”

Ante la muerte, las palabras solo atestiguan.

– Yamil Maldonado Pérez, “Esta noche todos mis muertos me acompañan”

In 2014, when Palestinian Chilean novelist, essayist, and scholar Lina Meruane returned to Palestine “in place of the other,” of her father and grandfather, to whom the Israeli state had repeatedly denied the right to return, what most shocked her was the silence. Yet as she ponders in her 2023 book Palestina en pedazos, surely there must have been “an incessant bustle” before the displacement. Back in New York after her trip, Meruane’s elderly neighbor, a “Russian-Jewish-woman-from-the-diaspora,” shares just such a memory: “that the pogroms her mother had escaped were preceded by noise. Horseshoes on the cobblestones. Shattered glass.” Meruane observes: “Only then did the silence break… The silence weighed on them as it does now on the streets of Hebron.”

As a member of the 500,000-strong diaspora in Chile, Meruane forms part of the largest community of Palestinians not only in Latin America and the Caribbean, but outside the Arab world. For her, as for many other Palestinians born in exile in the region, the silence that accompanies genocide is not simply a mark of absence and loss; it reveals something about the world. Just months after Meruane returned from her 2014 visit, the Israeli state killed more than 2,000 Palestinians during its so-called Operation Protective Edge. A decade later, the writing and editing of these pages happened as we, collectively, bore witness to yet another Israeli assault on Palestine, this time of genocidal proportions.

This issue of the NACLA Report explores transcontinental encounters between the land from the river and the sea and the land we know as the Americas. Attending to collective realities, interconnected struggles, and geographies of violence, authors examine solidarities extended by states and pueblos, from above and below, from Abya Yala to Palestine. At a time when news from Gaza presents seemingly endless horrors, and frustration with political leaders here in the heart of empire continues to deepen, these pieces chart nodes in a global network of anticolonial consciousness and solidarity.

More than 500 years into the colonization of the Americas, an important project within the “Indigenous renaissance,” as Maya Jakaltek scholar Víctor Montejo has termed it, has been to reconceptualize these lands as Abya Yala or Abiayala. Loosely translated to “land of full maturity,” Abya Yala is the word the Guna people of the region otherwise known as Panama and Colombia used to refer to the present world. Since the late 1970s, when the Guna offered the term to Aymara leader Takir Mamani of Kolla Suyu (Bolivia), the concept has taken on a hemispheric significance. As we put this region in conversation with another land suffering under a violent settler colonial project, we intentionally use Abya Yala to read through colonial impositions, such as borders, and to elevate the societies creating and sustaining life in the face of dispossession. While many authors in this issue speak of Latin America and the realities of the colonial state and politics as they exist today, others engage with Abya Yala as a prism through which to view the connections among pueblos, or peoples, in spite of and in opposition to the state.

In Abya Yala and beyond, the ongoing Israeli genocide in Gaza has animated a global movement that decries the violence as an affront not only to the lives of Palestinians but to humanity as a whole. Yet, such powerful sentiments risk becoming empty words if they are not grounded in a structural analysis of the global reach of European settler colonialism and the liberation movements that have emerged in its wake. In this spirit, this issue is anchored in two ways: from above and from below. Addressing state-level forms of collaboration, whether in the name of oppression or solidarity, the pieces in this issue critically examine the colonial and modern logics that make the ongoing dispossession—and elimination—of the peoples of Abya Yala and Palestine possible. From below, authors look at the weavings of grassroots solidarity that stitch together these two lands.

Writing in this issue, activist-scholars Linda Quiquivix and Mohamed Abdou trace the historical ties between Palestine and Abya Yala to 1492, when the forced conversion and systematic expulsion of Jews and Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula set the foundation for the white Christian supremacist rule that was then exported to the rest of the world. In the “new world” founded by Columbus, the only way out for those below is to go above; they may access power so long as their ascendance is premised on the continued subjugation of others—it’s “the price of the ticket,” as James Baldwin used to say. In the struggle for a free Palestine and all our struggles, Quiquivix and Abdou remind us, we must resist becoming the monsters that we fight.

In recent decades, the ties between these two regions have been reinforced not only by the presence of a well-established Palestinian diaspora, but also by Israel’s consistent involvement in the continent’s affairs. As journalist Raúl Zibechi makes clear, the pro-Palestinian public position of many Latin American leaders today belies a deep history of collaboration with the Zionist state. From arming and training dictatorial regimes, to supplying the latest technologies to surveil activists and Indigenous communities, Israel has long maintained strong military and economic relations with countries of the region. Despite their public statements against the genocide, progressive governments like those in Chile and Brazil have not cut off these material ties.

Unsurprisingly, a clarion call for stronger action on Gaza has come from university campuses, where a rich history of student mobilizations in Latin America and the Caribbean has given rise to one of the most powerful nodes in the global geography of Palestine solidarity. In a roundtable conversation, activists from pro-Palestine university encampments in Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Puerto Rico share experiences and lessons from their struggles. “For comrades in the United States, in particular,” activist-scholar Conor Tomás Reed writes in the introduction to the dialogue, “these lessons hold the potential to catalyze new tactics for attacking and defeating Zionism and U.S. imperialism from within the belly of the beast.”

In her piece, historian Sandy Plácido further makes the case for building solidarity among oppressed peoples against the forces of colonial capitalism. In Ayiti—the Taíno name for the island shared today by the Dominican Republic and Haiti and the site of the first colonial settlement on the continent in 1492—the apartheid-like conditions faced by Haitians and Haitian-descendants mirrors the subjugation of Palestinians in the occupied territories. As technologies and tools of repression are shared across the world, Plácido argues, struggles against anti-Blackness and apartheid, too, are inherently global.

Similarly mapping interconnected histories of violence, anthropologist Carlota McAllister delves into the “special relationship” between Israel and Guatemala. At the height of Guatemala’s scorched-earth counterinsurgency in the early 1980s, Israel was dictator Efraín Ríos Montt’s most loyal backer. Countering denialism about both Ríos Montt’s genocide of Maya Ixil people and the ongoing extermination of Palestinians in Gaza today, McAllister powerfully affirms that there was and there is genocide. For McAllister, Israel and Guatemala’s long friendship—seemingly undisturbed by the rise of progressive President Bernardo Arévalo to power—reveals the limits of the liberal state.

In another roundtable conversation, facilitated by Alejandra Mejía of Migrant Roots Media, Latine organizers in the U.S. South draw on their understandings and experiences of U.S. imperialism to inform their expansive horizons in the struggle for Palestinian liberation. These activists make material connections between white supremacy, forced displacement, carceral regimes, capitalist exploitation, and empire in Palestine and what their families have faced as Brown immigrants to the United States. As one participant powerfully put it, “My solidarity with Palestine… stems from what I wish others would have done for my people.”

As multiple pieces in this issue show, such solidarity has deep roots. Historian Amy Fallas zooms in on March 1981, when Schafik Handal, secretary general of El Salvador’s Community Party and a founder of the FMLN guerrilla, traveled to Lebanon to meet with Palestinian resistance leaders on the eve of Israel’s invasion of the country. Handal was the son of Christian Palestinian immigrants, but at the heart of the ties he forged in Lebanon, Fallas writes, was his analysis of “a common struggle against the oppression meted out by the hegemonic alliance of U.S. and Israeli financial, material, and diplomatic interests.”

The limitations of identity-based frames, as highlighted by Handal’s politics, comes into focus when we consider how powerful conservative factions of the Palestinian diaspora in the region have allied themselves with political and economic elites. In the case of Chile, as anthropologist Siri Schwabe shows, conservative members of the Palestinian diaspora were key supporters of the Pinochet dictatorship. This explains one of the region’s most striking paradoxes: that the heads of state in El Salvador and the Dominican Republic, the Palestinian-descendant Nayib Bukele and Lebanese-descendant Luis Abinader, respectively, are among Israel’s most loyal supporters.

Or perhaps this is not a paradox at all. In the binary world of above versus below imposed through colonization, Europe’s “inferiors” have been able to become “superiors” at the expense of Indigenous and African peoples and at the cost of genocide and enslavement. Offering a path out of this binary thinking, scholar Sylvia Marcos, in dialogue in this issue with Linda Quiquivix, presents the Zapatista philosophy of “together and side by side.” Despite differences between them, Marcos says, both Palestinian and Zapatista struggles “are defending themselves against the violence of the capitalist system.”

In a world marked by the downfall and corruption of national liberation movements in the aftermath of the Cold War, this philosophy of side-by-side holds the promise to reinvigorate global anticolonial solidarities between Palestine, Abya Yala, and beyond. Recognizing that even the Palestinian diaspora in the Americas is a settler-colonial community seeking refuge, not unlike European Jews in Palestine, challenges us to think beyond liberal identity politics and tackle questions of how power circulates, genocides are rationalized, and all our struggles reach across the globe. This is precisely why liberation movements in both contexts must rely on each other to articulate a new language of liberation that overcomes the trappings of the above-below dichotomy. As Schwabe so beautifully puts it, “Not only does this solidarity forge connections across great distances in space, but it also challenges imaginary divisions between here and there, then and now, us and them… break[ing] with static ideas about which pasts and which futures belong to whom and where.”

With heavy hearts and tired voices, facing police violence and censorship and repression and surveillance in our educational institutions and workplaces, denied our need to grieve and mourn the many thousands killed by the relentless U.S.- and Israeli- war machine, we must remain strong and defiant. We hope readers come away from these pages with a deeper understanding of the historical and global context of Palestine solidarity. From below, this issue aspires to be a humble contribution to the living history of solidarity between the pueblos of Abya Yala and Palestine who have collectively carried on deep forms of shared struggle. ¡Kausachun Palestina! ¡Jallalla Palestina! ¡Newen Palestina! ¡Viva Palestina!

In this spirit, we dedicate this issue to the tens of thousands of Palestinian and Lebanese children, women, and men killed during the latest wave of U.S.-backed Israeli genocidal violence in 2023 and 2024, and to the millions of family members, compatriots, and comrades left irreparably scarred in its wake, for generations to come. May the martyred souls find the respite and justice that was stolen from them on this earth and may their descendants one day return to a free Palestine.

Sara Awartani is an interdisciplinary historian whose research and teaching focus on 20th-century U.S. social movements, interracial solidarities, policing, and American global power, with special attention to Latinx and Arab American radicalisms.

Pablo Seward Delaporte is an anthropologist whose work integrates anthropological, decolonial, and feminist theories of race and gender with ecological approaches to violence and care. He specializes in transnational Black, Indigenous, and Arab migration in Chile.

Linda Quiquivix is a geographer and popular educator raised by Palestinians, Zapatistas, Panthers, and jaguars. She is author of Palestine 1492: A Report Back (Wild Ox Books, 2024).

George Ygarza is a writer, translator and researcher. His work examines state power from above and resistance from below, serving as an interlocutor of pueblos across Turtle Island and Abya Yala.

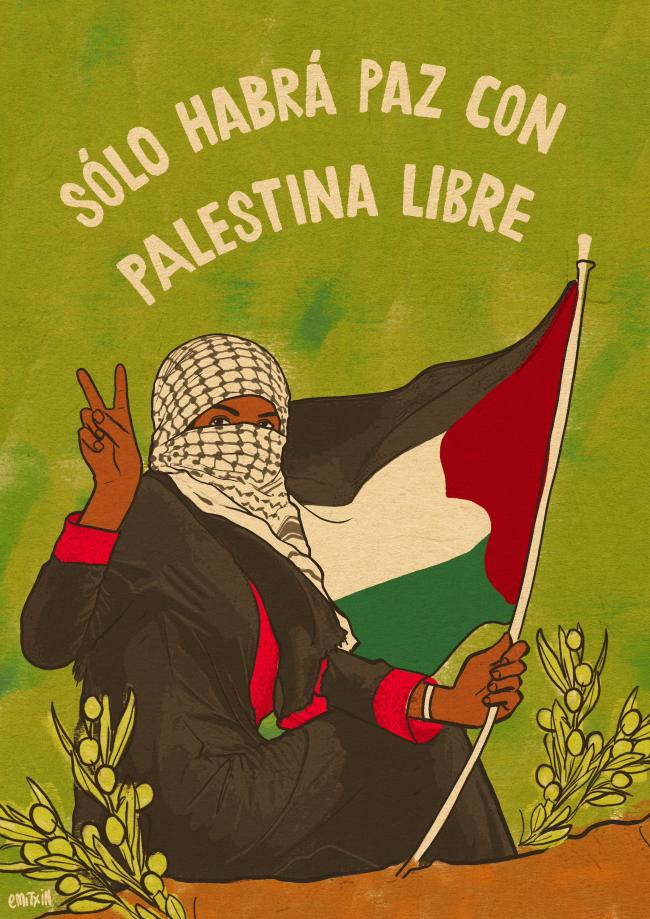

Cover Art by Linda Quiquivix: quiqui.org.