This article was originally published in German by Republik.

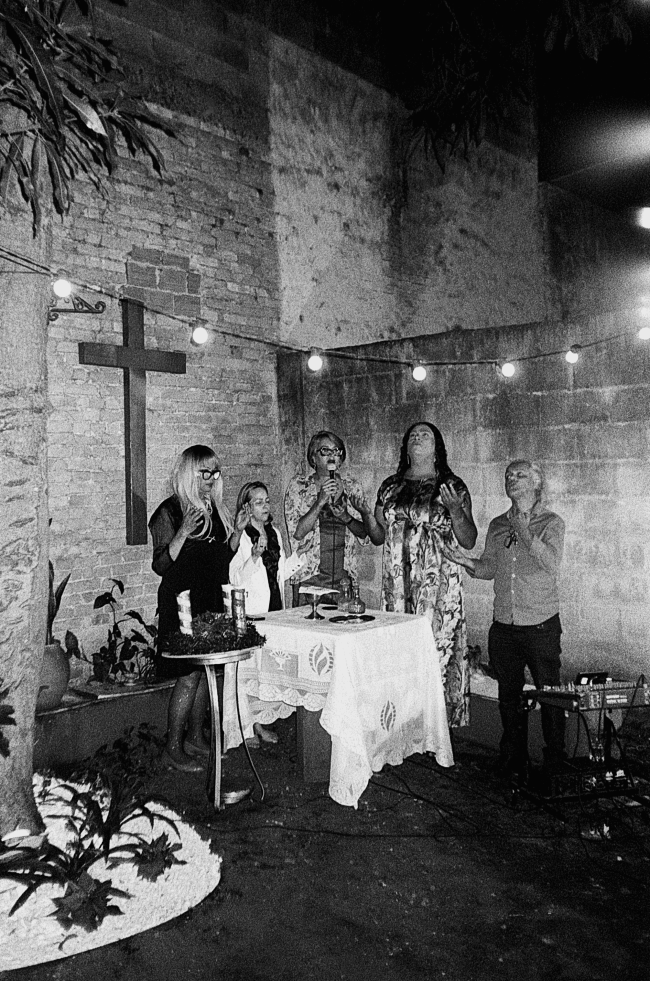

Jacque Chanel straightens her black dress, adjusts her straw-blond wig, then stalks forward to the small altar in front of the mango tree. She squints her eyes and begins to speak into a microphone in a sonorous voice. "Thank you, Lord, for allowing us to feel your power!" Stirring gospel music plays from a tape in the background. "Thank you, Lord, for your light!" About thirty people stand in front of the stage. Some ecstatically stretch their arms in the air, others murmur trance-like to themselves, bobbing their bodies like a pendulum in prayer. "Thank you, Lord, for your love!"

Chanel, 58—donning tattooed eyebrows and thick-rimmed glasses—is an evangelical pastor. Her open-air service is held in the courtyard of a nondescript row house. Behind a wall, the high-rise silhouettes of the mega-metropolis of São Paulo can just be made out. Several pastors are on hand that evening. Prayers, music, mass wine. At first glance, one might think: This is just a normal church service.

But this church is different. Chanel is trans. Together with some like-minded people, she founded the first church for trans people in Brazil.

In a country where fundamentalist Pentecostal churches are gaining more and more influence, Chanel's church is a small but active countermovement. And its struggle for recognition reflects a fundamental conflict in Brazilian society. About what faith is. About what the church should look like in the 21st century. And who belongs to it.

The world's largest Catholic country is undergoing what some in academia are calling a "religious revolution." More and more Brazilians are turning to Pentecostal churches. Fourteen thousand new evangelical churches open each year. There are calculations that predict that evangelicals will make up the majority of Brazil's population as early as 2032.

Evangelicalism is a theological current within Protestantism. As a rule, the congregations do not engage in critical exegesis of the Bible, what is written in the Bible is understood literally, and it is not questioned. In Brazil today, evangelical churches equally dominate the streetscape of the poor districts, the mostly affluent inner cities, and the remote villages.

Similar to the United States, there are huge, ultra-modern prestige buildings. Some of these churches have room for more than 20,000 worshippers, operate television studios and have helipads on the roof. But there are also small garage temples everywhere, often with only a few plastic chairs, a microphone, and loudspeaker boxes. Since, unlike the Catholic Church, there is no supreme faith authority, it is easy to start a new congregation. Almost anyone can call themselves a pastor. What it needs above all: charisma and a "divine calling."

Most churches are arch-conservative. They are against abortions, demonize many "worldly" things and categorically reject same-sex love. These strict dogmas impacted Chanel.

Chanel was born in 1964 in Belém, a city of millions in the north. She had always known that she was a woman and had a very feminine manner even as a child. One day, her devout mother packed a suitcase and dragged her to a pastor. Chanel was only 13. "She wanted Jesus to heal me," Chanel says.

From then on, she lived in the church basement, in a small room with no windows. The pastor became something like Chanel's surrogate father. He never wanted to talk about her identity, she says, but he respected her, and more importantly, he integrated her into the church community. "I was rejected by my family, but strengthened in my faith."

At 19, Chanel's life took another turn. Six men stormed the church and shot the pastor - in front of her. They were drug dealers, she says, unhappy with the house of worship in her neighborhood.

Like so many outsiders, she was drawn to the metropolis of São Paulo in the 1980s. She knew no one in the big city, and again religion gave her support. She went to church services, sang in the church choir, and became involved in youth groups.

Finally, she decided to undergo gender reassignment. And once again she became very lonely.

Countless times, she says, pastors put their hands on her forehead to exorcise an "evil spirit." Once she was called forward in a church service. The pastor quoted Bible verses, then yelled, "We don't want anything like you here."

She says she experienced “much suffering” in church. Despite it all, Chanel doesn't seem bitter when she tells her story. She has a calm, almost stoic manner. It never occurred to her to break with her faith. But the fact that she had no spiritual place for a long time left a big hole. This emptiness almost destroyed her.

It was one day in July ten years ago that once again fundamentally changed her life. At the time, Chanel was running a small hair salon. A client entered her studio and they struck up a conversation. He told her he was a pastor. And gay. He invited her to a church service.

After work, Chanel took a bus to the suburbs of São Paulo. When she arrived at the address given, she couldn't believe her eyes at first. Warm light, rainbow flags, men with brightly colored hair. It was one of the first so-called inclusive churches in the country. "I couldn't stop crying," she recalls. "I thought to myself, 'Now I've finally found my place.'"

While the major Pentecostal churches are consistently conservative, the evangelical world is diverse. There is a scene apart from the fundamentalist hate preachers. Exact numbers do not exist, but there are now inclusive churches in several cities. At some point, however, Chanel was no longer happy even in the congregation on the outskirts of São Paulo. She was the only trans woman. And there, too, she experienced prejudice: "Trans people are the minority within the minority."

So she founded the first church for trans people in Brazil: Ministério Séforas, the Ministry of Zipporah. The name refers to a biblical figure, Moses's wife. Today, the small congregation is affiliated with the Brazilian offshoot of the Metropolitan Community Church. The inclusive church was founded in 1968 by gay pastor Troy Perry in Los Angeles. While there is support from the city government, Chanel says, they still rely on donations. And the Church has no building of its own; services are held in the homes of church members.

Chanel lives in a squat in the north of São Paulo. The half-finished concrete structure can be seen from afar. Originally, an Ibis hotel was supposed to be built here, but the owner went bankrupt during construction. The 15-story building stood empty for years before poor families settled in. Children play soccer in front of the building, and you can hear a jumble of French and Creole. Most of the families are from African countries or Haiti.

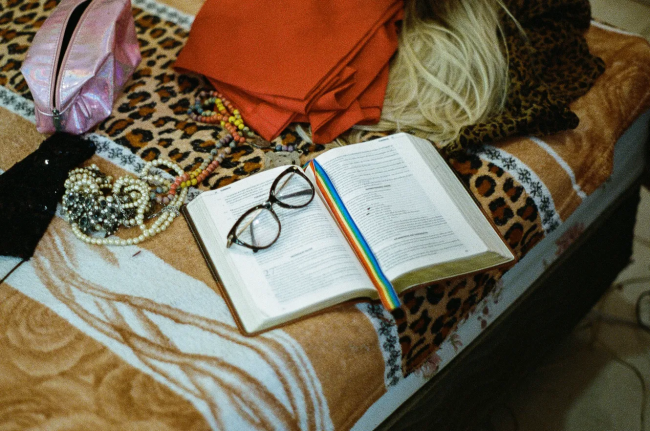

On the first floor, you pass through a dark hallway. Water drips from the ceiling into plastic buckets, cables hang out of the wall. Behind a heavy wooden door, Chanel lives in a large, untidy room. Parts of the ceiling are missing, fruit flies buzz everywhere. In one corner stands a make-up chest, on the bed lie wigs and a Bible.

She has had to listen to many terrible things, Chanel says. That she was not a true Christian, that her church was a work of Satan. Then Chanel replies: Jesus was also excluded, he was on the fringes of society. The "fundamentalists," she says, are those who betray the Bible: "They want to preach the Word of God, but spread hate."

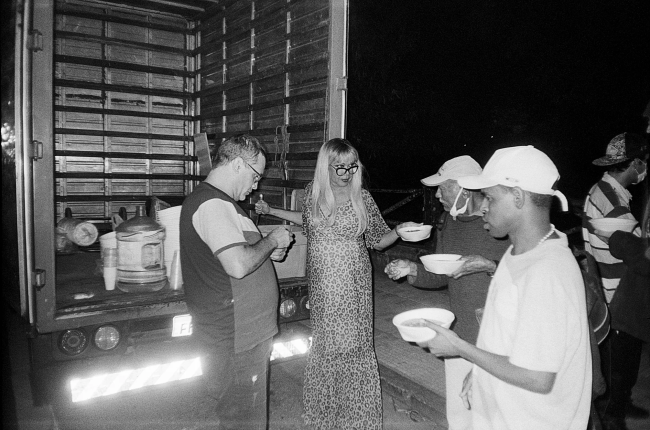

She was only accepted by others when they learned about her work. Chanel opens a door to the next room. Once a week, she cooks large quantities of food in the dilapidated industrial kitchen. She distributes the food to those in need. Sometimes someone from the community helps her, but often she is alone. "This is also religion for me," she says as she tosses finely chopped potatoes into a pot. "We want to put the gospel into practice."

Chanel and her circle see themselves as a countermovement to the large evangelical churches, many of which are suspected of shamelessly exploiting their believers. "Inclusive theology" is what they call their approach. They want to be with those at the bottom, those no one else wants to know about. In São Paulo, these are primarily the homeless. No one knows exactly how many people live on the streets in the largest city in the southern hemisphere. But their numbers are probably several tens of thousands.

After corruption scandals and a severe political crisis, Brazil slid into recession starting in 2014, from which the country's economy never really recovered. The pandemic also hit the country hard. Entire families are squatting in tent cities or on bare asphalt. Twenty-one million Brazilians are already starving, according to a UN study. Videos on YouTube show people digging through garbage trucks for leftover food.

Many trans people are also homeless. They are doubly discriminated against: because of their identity and because they live on the streets. Chanel says that many of these meninas, "girls," have barely seen the inside of a classroom and have no chance in the formal labor market. Sex work is often the only source of income. Few are able to escape the cycle of exclusion, poverty and the streets. According to the organization Associação Nacional de Travestis e Transexuais (National Association of Transvestites and Transsexuals, ANTRA), the life expectancy of trans people in Brazil is about 35 years. And Latin America's largest country is the world leader in homophobic and trans violence. One hundred thirty-one trans people were murdered in 2021.

In a deeply religious country like Brazil, religion is often the root of exclusion and hatred. But it also offers support and a home to many. In a survey conducted by the Vote LGBT+ project at the 2018 Pride parade in São Paulo, 35 percent of the participants declared that they were Christian. Unlike in Europe, blanket criticism of religion comes to nothing in most Latin American countries. Instead, the authority to interpret faith is fiercely contested.

Chanel says, Jesus also underwent a transformation: from divine soul to human soul. "Why shouldn't we be able to transform ourselves too?" And then she says, "It doesn't matter how much silicone you have in your breasts. It doesn't matter how big your wigs are. God loves you too."

Niklas Franzen is a journalist based in Berlin who worked as a Brazil correspondent for German newspapers. In May 2023, his book “Brasilien über alles: Bolsonaro und die rechte Revolte” (Brazil above everything: Bolsonaro and the Right-Wing Revolt) was published.

Felipe Avila (Photographer) lives in São Paulo, Brazil. He performed the exhibition “Masculino dócil” (Docile masculinity) in 2017 and published the photobooks “Corpo presente” (Body present) in 2019 and “No encontro tudo se dilui” (In the encounter everything is diluted) in 2022. He is an artist in transformation, who thinks of the camera as a tool that makes it possible to create through encounters with other people.