The week after Mother’s Day 2022, Camilo Beltrán received a devastating call from his mother at 3 am. His sister, Leidy Beltrán, had been murdered. At first, he couldn’t believe it. “I had spoken to her that morning,” Camilo recalls. But the reality was undeniable: Leidy’s partner had stabbed her in the heart in a fit of jealous rage.

Camilo Beltrán works as a teacher and lives in Kennedy, Bogotá. He remembers his sister, Leidy Beltrán, as a diligent woman dedicated to her family. One of her dreams was to see her two daughters grow up, finish school, and attend university. But on May 12, 2022, that dream was shattered when Leidy was murdered, and Camilo suddenly became the guardian of her daughters, who were then only four and 10 years old. The two girls are among many children left orphaned by a growing number of femicides in Colombia.

Before her murder, there were warning signs. Leidy's partner had shown possessive and jealous behavior, frequently monitoring her movements through video calls. Despite concerns raised by Camilo, Leidy insisted that things were fine. However, her life was cut short by her partner, Waldo Morales, who initially attempted to evade responsibility for the crime until security footage exposed the truth.

"We fought tirelessly to ensure justice, but because Morales turned himself in, his sentence was reduced," Camilo explains.

After Leidy's death, Camilo and his parents sought custody of Leidy’s daughters, now aged seven and 12. The process involved several interviews with the minors. Alongside his girlfriend, Camilo embraced the challenge of raising them, saying he never hesitated about assuming guardianship. The girls, particularly the youngest, faced significant emotional struggles. Initially, they were told their mother was unwell. But they found out the truth through social media, Camilo noted. Deeply affected by the tragedy, the younger girl began recounting the exact circumstances of her mother’s death to everyone she met.

The emotional toll on the family has been immense. “There’s no psychological or financial support from the state. The only help we received was three months of therapy for the younger girl, and that was it,” Camilo says. “The state isn’t prepared to address what happens after a femicide. It doesn’t ask if these children are okay.”

In addition to emotional stress, the economic consequences are also immense. Before the femicide, Camilo enjoyed using his income for hobbies like bike riding and traveling. Now, he invests in his sisters’ daughters, on things like food or medical support. In the future, he would like to earn a master’s degree, but with the present situation, he will have to save longer.

Despite the challenges, his nieces remain a source of strength for Camilo. "They’ve become the reason my parents and I keep going," he says. With the support of his girlfriend, he’s learning how to navigate parenting challenges, from managing teenage mood swings to addressing the girls’ trauma.

A Persistent State Crisis

According to the NGO Observatorio del Feminicidio in Colombia, 815 femicides were reported in 2024 alone in the country; the Attorney General acknowledged 640 cases by November. The discrepancy in the number of cases stems from different definitions of femicide. Many victims leave behind children, but no one knows the exact number.

The NGO attempts to estimate the number of orphans of femicide by counting each instance in which a news report mentions that a murdered woman was a mother or states how many children she left behind.

While femicide was codified as a crime in Colombia with the passage of the “Rosa Elvira Cely” law in 2015, there is still no official registry or state support for the children of victims. This systemic failure leaves hundreds of children facing deep psychological and economic hardships.

Under Colombian law, femicide is defined as the killing of a woman due to her gender identity and carries a minimum penalty of 250 months in prison. The law also mandates the creation of a femicide registry to track this persistent issue in Colombian society. However, there is no registry to document the children orphaned by these crimes. Additionally, 73 percent of femicides in Colombia between 2021 and 2023 went unsolved, according to the Red Nacional de Mujeres, highlighting a stark gap between the law’s intent and its enforcement.

“Regarding access to justice, a lot of work needs to be done,” Congresswoman Carolina Giraldo Botero stated, underscoring the gap between legislative intent and practical implementation. She sees the high workload the Attorney General faces as a possible explanation for the low rate of cases that have been successfully solved.

Psychologist Lorena Santana, who works with orphans of femicides, states, “Femicide affects the whole community. An orphan of a femicide is normally a victim of two parts: a mother who dies and a father who is the aggressor and who is in prison. The children are emotionally affected, depressed, anxious, and aggressive.“

“’No one has thought about what happens to the children’”

Camilo remembers how he marched in protests against femicides himself as a young student of the Universidad Pedagogica Nacional. “But I would have never thought I would live through it so closely,” he says. His personal tragedy has driven him to activism. He’s now part of Huérfanos por feminicidio Colombia (Orphans of femicide in Colombia), a collective advocating for legal recognition and support for children orphaned by femicide.

Camilo’s advocacy extends beyond political activism. He also regularly supports other families affected by femicide, offering guidance from his own experience and emotional support. "I speak with them because I understand what they’re going through. Sometimes, just listening makes a difference," he says.

The collective also organizes activities for orphaned children to help them process their grief. "The goal is to bring a smile to their faces, even if just for a moment," Camilo explains. For instance, they meet to share food to get to know them. One member of the group also has a specialization in social management, which helps them connect with the orphaned children.

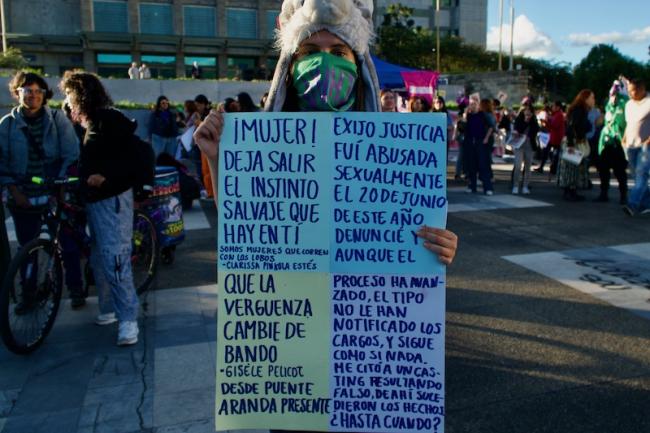

In August 2023, Congresswoman Botero led efforts in Congress to propose a bill that would ensure economic and psychological support for children of women killed by femicide. “So far, no one has thought about what happens to the children, many of whom are left in situations of poverty or extreme poverty,” Botero emphasizes. Other countries, such as the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, and Bolivia, have already made progress in this area. For example, Argentina has enacted Ley Brisa, which provides economic support to the children of femicide victims until they turn 21.

Among the most important points of the bill Botero proposes are the establishment of a registry, free psychological assistance, and providing orphans with resources to continue their education, such as preferable access to public schools and sports workshops. The proposal also includes one-time economic support for the funeral and monthly stipends for the minors of at least 456,000 pesos, which equals approximately 110 U.S. dollars. Leidy’s children will not benefit from the law economically anymore, as the law is not retroactive.

Nearly a year and a half has passed since the bill's initial proposal. Marcela Boyacá Mesa, co-founder of Huérfanos por feminicidio Colombia, hopes the bill will be approved soon. “In the first place it is a recognition of the existence of the population, of a problem and the intention to provide solutions.” The draft has already passed two debates in the House of Representatives, but two debates in the Senate are missing—if they do not occur by the end of the legislative period on June 20, the project will expire. “We are asking with all of our heart that the proposal will be discussed soon, so we do not lose all this work,” says Botero.

“We need a cultural change. Because we have a lot of machismo in our society. That is why there are so many femicides,” explains Botero. She also emphasizes the importance of gender-based violence prevention. In addition to femicides, rates of domestic violence are high in Colombia. For instance, the city of Bogotá reported 42,000 cases of domestic violence in 2024. Last year, one woman was killed by a former partner in a mall, witnessed by many visitors.

In 2023, Colombia even declared a public emergency for gender-based violence. To help women understand the first signs of violence, the government has introduced the concept of the “Violontometro,” a tool helping women assess the level of gender violence on a scale from yellow (hurtful jokes) to red (physical attacks or threats of murder). The “Purple Hotline” in Bogotá also offers instant psychological assistance or police protection for those who experienced gender-based violence. However, there are presently no long-term programs specifically designed for the orphans of femicide.

But Congresswoman Botero is determined to see the proposed law become a reality. She plans to support prevention, which for her includes teaching women about the signals of violence and, more importantly, working with men to reflect on their role in society. “No children should have to grow up without their mothers.”

Anna Abraham is a German journalist with a background in International Relations.

Tony Kirby is a Bogotá-based journalist covering Indigenous rights, climate, and environmental issues across Latin America. He has reported from Ukraine during the Russian invasion and has worked with refugees throughout the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

Sergio Alejandro Melgarejo García is a Colombian filmmaker and documentalist with a strong experience as a storyteller.