This web exclusive piece is part of our Summer 2024 issue of the NACLA Report.

Leer este artículo en español.

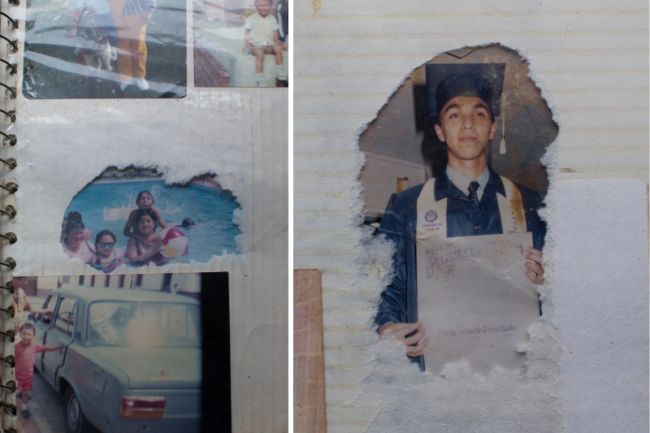

On the walls of Beatriz Méndez’s home hang photos of Weimar and Edward, her son and nephew. The young men were 19 years old when Colombian soldiers dressed them in military fatigues and murdered them in June 2004, in Ciudad Bolívar, in the south of Bogotá. Four years later, another 19 young people disappeared a few miles away, in Soacha, after unidentified men offered them work in the countryside. Their bodies were found in Ocaña, in the Norte de Santander department, 400 miles from their homes. The military reported them as guerrilla rebels killed in combat.

A group of mothers and other relatives of Soacha reported to the media that military officials were covering up the truth. In front of the cameras, they declared that their children were students and workers, clarifying that the young men never belonged to armed groups. Their children were not victimizers, they were victims. The mothers demanded that the state explain who had kidnapped and murdered their children and why their bodies had appeared in mass graves, dressed in camouflage clothing. Thus came to light the story of the largest crime of extrajudicial killings documented in recent Colombian history: the “false positives,” as the case is euphemistically known.

Today, visiting the homes of mothers like Beatriz in southern Bogotá is like entering an intimate and personal museum that tells the story of years of struggle and mourning. The Mothers of the False Positives of Soacha and Bogotá (Mafapo), an organization known in Colombia as the Mothers of Soacha and made up not only of mothers but also sisters of victims, has fought for 16 years to uncover and demand “the total truth” about what happened to their loved ones. They know the state continues to hide large parts of this public secret. Over the years, these women have taken over public space with their speeches, objects, and creative interventions, producing a series of artifacts such as posters, banners, textiles, photographs, murals, plays, performances, crafts, and paintings. Each in their own way, these unique repertoires function not only as powerful representations of their demands and disputes with the state, but also as channels of healing.

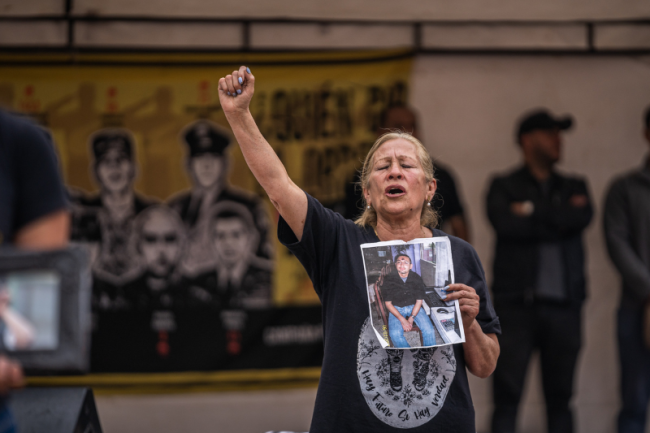

The Mothers of Soacha have used their objects to make visible what others seek to hide, becoming a powerful counterpublic, to borrow from Nancy Fraser. This counterpublic designs means of expression with which the Mothers challenge and destabilize official narratives about extrajudicial executions and disappearances ordered by the Colombian state.

Who Gave the Order?

Between 2000 and 2008, the Colombian military abducted and killed at least 6,402 civilians, passing them off as guerrillas killed in combat. Most of the victims were young men, in their early 20s, from impoverished or marginalized communities. The strategy of counting and rewarding combat casualties was heavily promoted under President Álvaro Uribe Vélez, in office from 2002 to 2010, a period that accounts for 78 percent of all extrajudicial killings of civilians committed throughout the armed conflict, according to the Truth Commission’s final report. The murders were part of an internal criminal system that offered rewards for those who accumulated the most rebel deaths. In exchange, soldiers received promotions, cash, extra vacation days, cigarettes, pizzas, and fried chicken.

Recent investigations and reports from the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) and the Truth Commission have confirmed that the state used these extrajudicial killings to construct a narrative showing that the military was winning the war against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the oldest guerrilla in the Americas and the government’s number-one enemy.

In her 2020 book Design and Political Dissent: Spaces, Visuals, Materialities, Jilly Traganou describes how different civic movements have found nonverbal forms of creative resistance through artifacts and actions of dissent. These repertoires of political contestation are anchored in the physical world, taking the form of disobedient objects, insurgent practices, material archives, and various creative assemblages that demonstrate and embody discontent and dissent.

One of the most powerful visual artifacts produced by a Colombian social movement deals with the issue of false positives. The mural ¿Quién dio la orden? (Who gave the order?), spearheaded by the National Movement of Victims of State Crimes (Movice), first appeared in Bogotá in October 2019 and showed the faces of five generals and a corresponding number of extrajudicial killings allegedly carried out under their command. The large-format image was installed next to a military academy and sparked a national controversy. Within hours, military personnel covered it up with white paint. The mural was put up several more times and was repeatedly altered. This tension catalyzed the image going viral on social media and set off a legal battle. Two years later, with a court ruling recognizing victims’ right to free expression, the mural was repainted outside the military academy, now with the faces of 14 generals.

The Mothers of Soacha participated in creating ¿Quién dio la ordén?. Together with various victims’ groups, they translated the mural into all kinds of objects: fabrics, shirts, posters, graffiti, mugs. All these objects were present in Beatriz’s house—in the dining room, the kitchen, the bedrooms—in the form of posters and stickers stuck on the door, refrigerator, and windows.

Beatriz also showed me the pamphlet for Develaciones, a play about the armed conflict, presented publicly by the Truth Commission in conjunction with the release of its final report in 2022, that depicted the Mothers of Soacha and other groups. She showed me, as well, the black and white images of a photography project in which some of the mothers were partially buried in earth beside a cemetery. Then, she showed me a piece of fabric on which she had sewed together scraps to create shapes and figures that reminded her of her son: the house where they lived, the flowers in the garden, the men who killed him. Getting together with other artists to sew tapestries about their stories and create artifacts of memory has served as a form of therapy for the mothers to heal collectively.

For years, the Colombian state’s official narrative explained the extrajudicial killings of the false positive victims as isolated errors committed by a small number of soldiers—“bad apples” who had overstepped. As victims’ organizations compiled databases and began reporting that the number of such murders could exceed 5,000, government and military officials questioned the source of their statistics, calling them exaggerated.

Thanks to the demands of the Mothers and other victims’ groups, civil society organizations and the JEP peace tribunal prioritized investigations that revealed that the killings did, in fact, number in the thousands, and that dozens of military men were involved in planning and systematically carrying them out across the country. Although for years the state refused to recognize the seriousness of these crimes, the Truth Commission confirmed in its 2022 final report that, out of nearly six decades of armed conflict, the false positives represent the most serious period of state violations of the right to life.

State violence against the Mothers radically transformed their lives. It changed their ways of thinking and shaped their political practices as well as their bodies, turning them into critical and visible women. Faced with a lack of explanation for the kidnapping, disappearance, and murder of their children at the hands of a state that was supposed to protect them, the Mothers abandoned their private spaces and became powerful public political subjects.

Embodied Memories

In 2016, several years after the disappearance and killing of their loved ones, some mothers and other relatives of victims of extrajudicial killings accepted a proposal from Dutch photographer Niels Van Iperen to get tattoos of the names and faces of the victims as part of his “Never Again” project. Doris Tejada, the mother of Óscar Alexander Morales, who disappeared on December 31, 2007 in the city of Cúcuta, was the first to accept. “My only condition was that I wanted a big tattoo: my son’s face on my right arm,” she told me.

For the mothers, the studio sessions were powerful rituals of mourning. “The day I got the tattoo, I felt like all the pain I had inside was coming out through the needles of the machine. I don't know if getting a tattoo hurts that much, but what I felt that day were rivers of pain releasing through my arm,” Doris said.

At least 10 mothers and family members have gotten tattoos of their children or other loved ones. These tattoos have opened paths of resistance and personal and collective healing. Tattooed on their skin, the names and faces of their children bring back the dead, giving the mothers agency and creating new bonds between them and their children. Their tattoos and their bodies have become intimate spaces of self-repair, memorialization, and channels of communication with their deceased children.

Beatriz has three tattoos: a portrait of her son Weimar on her left arm, an angel on her back adorned with her nephew Edward’s name, and a butterfly, a symbol of her transformation from a shy rural woman into one of Colombia’s most visible human rights defenders. “The death of my son forced me to transform into another person,” she told me at her home in Bogotá.

Doris feels her son Óscar’s presence every day. He accompanies her to marches and during searches for the disappeared in cemeteries. “I don’t need a sign at protests because I carry his image on my skin. I take it with me on my search trips. It helps me search for his remains and to find the children of other mothers,” Doris told me when I interviewed her in late 2023. “I will carry this 73-year-old body and my son until I’m gone. When he died, he was 26 years old, and now he is 41.”

In April 2024, 16 years after Óscar’s disappearance, Doris received news that Colombia’s Search Unit for Disappeared Persons had identified his remains, recovered from a cemetery in El Copey, in the department of Cesar.

For Beatriz and Doris, their children regained their presence in this world through their tattoos. Through the bodies of their mothers, Weimar and Óscar have a body again, a body in which they now live together, continue to communicate, and even, in a way, grow old. “While they were tattooing me, little by little, my son’s face appeared on my arm, and I recognized his gaze. It was him, my son, again, so beautiful, reincarnated in my body, my flesh and my blood,” said Beatriz.

Their tattoos have turned the mothers into living monuments—monuments that do not need the permission of a mayor to be built, that do not take years to erect, that do not require bureaucratic procedures through which narratives get negotiated. “Cement monuments are created and then torn down, but nothing like that can happen to my monument,” Beatriz told me.

Blanca Monroy got a tattoo on her left arm of the same scales of justice that her son, Julián, bore in the same place. This tattoo had helped identify his body when it was recovered from a mass grave some 400 miles from Soacha, six months after he was abducted in March 2008.

In her 2020 book ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence, New York University performance studies professor Diana Taylor describes that being present is simultaneously an act, a word, a gesture, an attitude, a recognition, and a response to authority, a battle cry against invalidation. In Taylor’s light, the apparitions of the Mothers of Soacha, their living monument, could be read as a presence that manages to disturb, upset, and interrupt political hierarchies and structures and their legitimizing discourses.

The Mothers activate their living monument through their performances and through the altars they install at talks to university students or outside of courts, during legal hearings. Their deceased children are also part of the monument, returning to this plane through their mothers’ tattoos. The Mothers’ repertoires of healing and dissent expand their presence in the public and political spheres in which they participate. This recharged presence functions as a solid system of protest, communicating counter-power and memorializing their dead. From the mothers, their tattoos, and their objects, a new body emerges.

Two Monuments

Through their living monument, the Mothers have demanded that the Colombian government offer concrete actions of reparation and recognition, including the installation of a physical memorial in Bogotá. In a place where the official narrative is publicly questioned, the memorial would make visible the number of 6,402 killed and serve as a meeting point for the victims and their communities.

On April 16, 2023, the Mothers commemorated 15 years of struggle in the main square of Soacha, the place where they have repeatedly asked the government to erect a physical monument to their cases. For years, the Mothers imagined the monument in many different forms: a fountain, a garden, an obelisk. They envisioned a mausoleum to store the ashes of the victims, as well as a memorial with 19 statues, standing with their arms open to the sky. Despite not yet becoming a reality, the long-awaited monument exists and operates from their imaginations, generating discomfort and tensions. The monument has been drawn in architectural plans and projected in budgets on multiple occasions.

But the creation of the memorial has been a promise repeatedly broken, living in the words of ministers, mayors, and presidents. President Gustavo Petro was the latest one to utter such a promise. On March 11, 2023, he traveled to Soacha and, speaking to a packed arena, called the false positives the “worst crime against humanity in the Americas in recent history.” Then, as expected, he pledged to create in Soacha “a great monument” to “close this Dantesque chapter in Colombian history in which a state murdered its own society.”

After this promise, the Mothers worked for six months with the Ministry of Culture to conceptualize a new memorial. In December 2023, the women presented the result: a model of a memory park and cultural center, designed with circular architecture around a central tree and other trees surrounding it. The Mothers explained that the plan is inspired by the body of a woman giving birth, and by the relationship between a mother and her children.

Although there’s a promise to build the memorial park in Soacha, it is difficult to estimate when it may become a reality. Similar projects, such as the construction of the National Museum of Historical Memory, which the state committed to building in 2011, have been the subject of political disputes that have prevented them from coming into being. Today, the museum—structurally flawed and partially built in the center of Bogotá—is abandoned. It is a project marked by a lack of financing, struggles for truth, and a series of corruption cases linked to its construction.

Memorials are ultimately spaces where society negotiates the narratives on which it stands. While Petro has announced that the false positives monument will create the possibility of “closing a chapter” of painful history, for the Mothers, the opposite is true. The memorial they imagine is not designed for the state to pay off its historical debts, get some relief, embrace the Mothers, and close the case. Important pieces of the public secret remain hidden: the Mothers have denounced that the testimonies given by members of the military in the JEP transitional justice proceedings have lacked essential information.

Military personnel themselves have told the Mothers that their testimonies are subject to the control of third parties, and that they can’t say everything they know because it’s too risky to do so. Many bodies of murdered young people are still missing, buried in mass graves or clandestine cemeteries that the Colombian state refuses to reopen, despite having information about their whereabouts. The cases of the deaths of these women’s loved ones are far from closed.

Translated from Spanish by NACLA.

Angélica Cuevas-Guarnizo is a journalist and curator focused on human rights issues. She has a master's degree in Anthropology and Design from The New School and is currently communications coordinator for ESCR-Net–International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in New York.