This piece appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

On Tuesday, March 1, during an early morning invasion in Gamboa de Baixo, a coastal community in Brazil’s northeastern city of Salvador, the Bahia state military police executed three young Black people: 16-year-old Patrick Sapucaia, 20-year-old Alexandre Santos dos Reis, and 22-year-old Cleberson Guimarães.

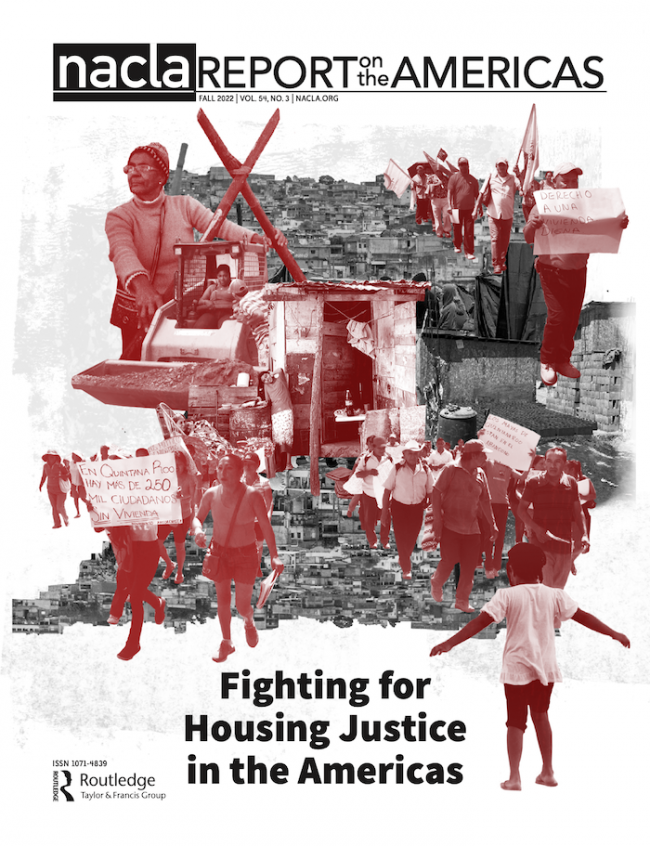

Tuesday afternoons are when I usually meet with three Brazilian colleagues—long-time Gamboa activist Ana Cristina da Silva Caminha, urbanism graduate student and codesigner of this issue’s cover art Matheus Tanajura, and literature professor and writer Claudia Santos—to discuss our graphic novel project, tentatively entitled A Coveted Paradise. The project illustrates the lives and political stories of the mostly women activists and collaborative scholars who have dedicated their lives to Gamboa de Baixo’s struggle. For three decades, these women have battled the developers and the police to resist forced displacement and to claim their rightful place on the city’s coastal lands. I document their arduous fight for collective land ownership, housing construction, and infrastructural improvement in my 2013 book Black Women against the Land Grab: The Fight for Racial Justice in Brazil.

Today, as a result of persistent struggle, Gamboa de Baixo remains. It is one of the few Black communities occupying the coastal lands of the Bay of All Saints, where, over the last 30 years, luxury apartment buildings and yacht clubs have replaced traditional fishing villages, destroying housing, local customs, and human lives in the process. The deaths of Patrick, Alexandre, and Cleberson were a heartbreaking reminder for Gamboa residents, and poor Black communities in general, that the violent siege on their “coveted paradise” is ongoing. So, too, is their resistance.

Matheus, Ana, and other activists of the Articulation of Movements and Communities of the Old Center of Salvador penned a public statement denouncing the police killings, cruelty, and generalized terrorization of the neighborhood. “Beyond the executions,” they wrote, “they shot at random, and they threw gas bombs down onto the community from the top of Contorno Avenue.”

As a friend and colleague living thousands of miles away from Gamboa de Baixo, these moments of violence are always difficult to process. In a small fishing colony, everyone is family. The traditional family name Sapucaia, for example, is also a street name. Young people like Patrick, Alexandre, and Cleberson are the children of women already bearing the brunt of racialized poverty, the threat of housing and land loss, and the lack of adequate public health care and education. I thought about these mothers losing their sons and the unimaginable grief that still shakes the community months later. Resistance and fear exist side by side, and I wondered where these women found the courage to speak out against the terror of everyday life. “Somos gente,” we are people, they screamed in agony.

Feminist, Black, Indigenous, housing, and land movements from around the country cosigned the Articulation’s letter, showing the magnitude of the massacre’s impact and the vastness of expressions of solidarity. A memorial held a week later on March 7 brought together people from neighborhoods across Salvador who knew what it means to live under the constant threat of deadly police operations while also resisting real estate speculation, gentrification, and forced evictions.

In the wake of the Gamboa massacre, historian Luciana Brito, guest editor of the Summer 2022 issue of the NACLA Report on Brazil, wrote a powerful essay on Black women’s political courage. Salvador, the city with the largest Black population in the African diaspora, is home to two realities, she explains: “The other Salvador is that of Black people, especially Black women, who need to go to the streets [and] shout in front of the cameras [to state] the obvious: that they are human beings, [standing] in front of impassable policemen who want to spread their blood on the asphalt.” In 2020, police killed 381 people in Salvador, and in every case with race-based data available, the victim was Black. Despite this statistic, Brito underscores, “no measure of public commitment was made...for the life of Black people.” According to the Brazilian Public Security Forum, 84.1 percent of the 43,171 people killed by police between 2013 and 2021 were Black, making Black Brazilians four and a half times more likely to be killed by police than their white counterparts. Among the latest atrocities, a massacre in the Complexo do Alemão neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro between July 21 and 22 left 19 dead. The city’s recent history lays bare the deep connection between this violence and housing rights: in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games, mass demolitions of homes in Rio’s poorest neighborhoods coincided with an increase in militarized policing and everyday state terror.

This issue of the NACLA Report explores the current housing crisis in Latin America and the Caribbean as a reflection of a global phenomenon of devastation in cities and the mass negation of the basic human right to life and dignified living. It also highlights the political urgency of collectively addressing police violence alongside issues of public health, education, immigration, housing, land, and urban infrastructure. The poor Black women who courageously reject the police’s version of events in neighborhoods like Gamboa de Baixo encourage us to see and hear what the marginalized, dispossessed, stateless, and houseless are telling us.

The pieces in this issue do just that. They document experiences and struggles in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Chile, Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina and show a collective insistence that human beings are worthy of life and protection. In this sense, the contributors in these pages show how and why housing has become one of the most critical social and political issues today. The violence of mass evictions and homelessness has led to the emergence of vibrant social movements aimed at transforming how we conceptualize ideas such as “the right to housing” and “the right to the city” as fundamental aspects of citizenship, belonging, and justice.

More importantly, these essays show how housing struggles have become fervent spaces for critiquing interrelated forms of inequality such as sexism, ablism, homophobia, and anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism. Housing justice, for these writers, cannot stop at the material construction of shelter. Rather, it must also include building homespaces, cities, and societies that envision and implement new forms of social and political engagement attuned to the vastness of human difference. Those of us who fight for the right to dignified housing must always contemplate police and prison abolition as part of that global project. As Christelle Jasmin’s review of Danielle S. Rudes’s Surviving Solitary shows, for instance, one of the most critical housing issues of our time is the continuation of state-sanctioned segregated housing in U.S. prisons. In the United States and beyond, millions of people experience homelessness after incarceration, are punished with house arrest, or, as in the case of São Paulo houseless activist Preta Ferreira, are incarcerated because of their direct involvement in housing justice movements. And houseless Black women, as Magali da Silva Almeida, Gracyelle Costa Ferreira, Christen A. Smith, and Michaela Machicote analyze, are often fleeing the terror of homeplaces.

As Argentine activist Leonor Rojas says in an interview with Valeria Procupez, “housing is only the beginning.” Despite the violence, the stories told in this issue—from Maya migrants resisting eviction in Cancún to Black girls seeing the beach for the first time in Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro to hip hop artists writing rebellious lyrics in Alamar, Havana—collectively convey the powerful possibility of building coalitions and new communities in cities and beyond national borders. It is my hope that reading these essays together will facilitate cross-geographic understanding and cultivate transnational methods of struggle and solidarity in the global housing justice movement.

This issue uplifts the brave mothers of Patrick, Alexandre, and Cleberson, who demand dignity for their sons and Gamboa de Baixo. In her essay “Homeplace: A Site of Resistance,” first published in the 1990 Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics, African-American feminist bell hooks offered an ode to Black women that aptly sums up the political spirit of this issue. “I want us to honor them, not because they suffer but because they continue to struggle in the midst of suffering, because they continue to resist,” she wrote. “I want to speak about the importance of homeplace in the midst of oppression and domination, of homeplace as a site of resistance and liberation struggle.”

See more from this issue and check out the table of contents.

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry is the Presidential Penn Compact Associate Professor of Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. With an emphasis on the United States, Jamaica, and Brazil, she continues to write on issues of Black women’s political thought and activism around land rights and housing justice in the African diaspora.

Cover art by Colectivo TRAMA (Atailon Matos, Flora Tavares, Luisa Caria, Lucas Ribeiro, Marina Muniz, Marina Novaes, Matheus Tanajura, Zara Rodrigues)