In the early years of Chile’s transition to democracy following the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, only one crime committed during the era was not covered by the 1978 Amnesty Law—Chilean economist and diplomat Orlando Letelier’s murder by car bomb in Washington in 1976. Braving stormy weather in a small plane on September 17, 1991, four detectives investigating the case approached Puerto Montt with an arrest warrant for the former National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) chief Manuel Contreras. Although Pinochet’s rule had ended, Contreras still swore allegiance to the former dictator and took orders from no one else. Fortunately for the detectives, Pinochet had ordered Contreras to cooperate with the them. Contreras’s storied arrest is symbolic of how much influence Pinochet wielded over the democratic transition and criminal investigations into atrocities committed by his own regime. The post-dictatorship government of Patricio Aylwin barely scratched the surface of investigating these crimes in terms of justice, accountability, and memory.

From September 11, 1973 until March 11, 1990, Chile was ruled by the U.S.-backed Pinochet dictatorship, during which almost 3,000 Chileans were killed or disappeared and over 40,000 Chileans were detained and tortured. Chile played a prominent role in Operation Condor, the U.S.-sponsored operation of surveillance and attempted annihilation of socialist and communist adherence in Latin America. In 1988, Pinochet lost a referendum which would have seen him govern Chile for another eight years. The following year, Patricio Aylwin won the first democratic elections held after the dictatorship. Far from being tried and imprisoned for his crimes, Pinochet became Commander in Chief of the Chilean military until 1998. With such a powerful position directly tied to the regime’s main repressive institution, Chile’s post-dictatorship transition to democracy was a tumultuous period, during which justice was thwarted by state institutions still swathed in Pinochet’s influence and legacy.

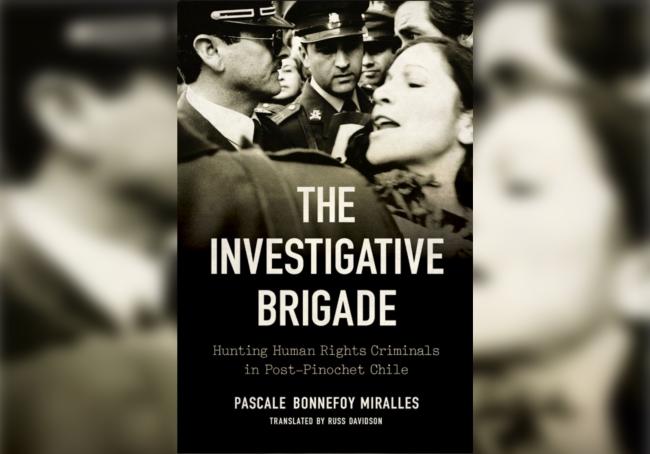

Pascale Bonnefoy Miralles’s book The Investigative Brigade: Hunting Human Rights Criminals in Post Pinochet Chile, unravels the extent to which democratically elected governments of the Concertación—a coalition of center-left governments that ruled from 1990 until Sebastian Pinera’s right-wing electoral victory in 2010—had to collaborate and, at times, compromise with departments in which Pinochet’s security agents still worked. Meanwhile, the Rettig Commission, which documented testimonies of Chileans who had been imprisoned and tortured during the dictatorship, emphasized the necessity of bringing the perpetrators to justice. Bonnefoy’s book describes the fraught search for dictatorship criminals during Chile’s turbulent democratic transition and reveals the extent to which the construction of democracy in Chile was still influenced by the specter of its dictator.

Bonnefoy’s fast paced narrative focuses on well-known National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) agents and a few of the dictatorship’s most famous crimes, including the murders of Letelier in Washington and United Nations Spanish-Chilean diplomat Carmelo Soria in Santiago. The text also recounts the secretive organization Colonial Dignidad, a German colony founded by former Nazi Paul Schafer, which also functioned as a detention and torture center for DINA. The cases discussed demonstrate how the dictatorship’s amnesty laws hindered the pursuit of justice, and reveal a widespread culture of persecution of dictatorship opponents by Pinochet loyalists. The book also details the well-known dictatorship operations related to the torture, killing, and disappearance of Chilean dissidents and the obstacles faced by detectives as they battled the remnants of Pinochet’s influence on the country’s democratic transition. Of particular importance is the book’s focus on how vital the testimonies of the Rettig Commission report were in building a clearer picture of DINA, its members, and its operations.

Obstacles to Pursuing Justice

With this book, Bonnefoy wanted to “portray a period in Chile’s recent past illuminated by its complexity and instability, when a model of transitional justice was continually tested and the shadow of military power still loomed.” Contreras’s arrest is one example of this challenge: when detectives presented Contreras with the arrest warrant, the former DINA chief said that he would comply only because he had received a fax from Pinochet instructing him to do so. Bonnefoy notes, “Contreras was demonstrating that General Pinochet was superior to the Supreme Court and had total control over the situation.”

Upon relinquishing power, Pinochet imposed certain conditions, demanding that the new government retain the neoliberal model, uphold the regime’s 1978 Amnesty Law, and prevent politically motivated reprisal attempts. Bonnefoy documents the constraints faced by the Aylwin government, including the fact that the Supreme Court was still presided over by dictator-era judges. As the military continued to oppose investigations into human rights violations, Aylwin was coerced into a compromise. In order to avoid confrontation with the army, the government decided in 1989 to prioritize revealing the truth about human rights abuses over seeking criminal prosecution. Prosecuting DINA and Pinochet, Aylwin said, would have sparked “a civil war.” “According to the logic of the military and those who supported the military’s reign,” writes Bonnefoy, “investigating crimes committed by agents of the state and imprisoning them was a politically motivated reprisal against patriots who risked their lives in 1973 to lift the country out of ruin and reestablish civic order because Chileans called for it.” A 1990 government report describes the military as “a key political actor” in the democratic transition, pitting Aylwin against a powerful institution that still declared its allegiance to Pinochet.

The Rettig Commission report laid the groundwork for later criminal prosecutions, as witnesses of dictatorship crimes came forth with testimonies. Bonnefoy analyzes the report and provides an overview of the discoveries of mass graves of the disappeared, painting a chilling picture of the dictatorship’s reach and its efforts to conceal its crimes. The discoveries of human remains in Lonquen, Pisagua, Futrono, Calama, La Veleidosa, Chihuio, and Copiapo prompted calls for Pinochet’s resignation from the army. The military retaliated by stating that individual accountability contradicted the existing government policy.

After Chile’s Investigations Police (PICH) investigated the atrocities carried out by DINA, many military personnel were prosecuted by the police through judicial orders, including former National Information Center (CNI) agents Patricio Castro and Alvaro Corbalan in 1990 and 1991, respectively. As Bonnefoy narrates, “The military had still not absorbed the fact that the police could act against them by means of a judicial order.” The Rettig report was mandatory reading for the detectives involved in tracking down and arresting DINA agents in the 1990s, yet these arrests occurred amidst a reckoning with the fact that PICH personnel, under whose auspices the detectives worked, were involved in at least 196 cases of disappeared Chileans.

Bonnefoy’s book also offers insight into the national political climate, which created delays as well as further injustices in the courts. The Aylwin Bill was one example of how the government attempted to thwart the courts by stipulating that the identities of people providing information on dictatorship crimes would be protected and the perpetrators guaranteed impunity. Ultimately, the bill did not pass because it was opposed by outraged human rights groups. But the post-dictatorship conciliatory politics that prioritized impunity for perpetrators ran against the Chilean collective memory, which was burdened with the trauma of relatives tortured, killed, and disappeared. In recognition of that collective trauma and in a further blow to DINA, the courts ruled in December 1992 that cases of the disappeared would be considered as open-ended abductions and thus not covered by the Amnesty Law of 1978.

On an international level, Operation Condor, the U.S.-backed regional plan that sought to annihilate all socialist and communist influence in Latin America, further complicated attempts to hold military agents accountable for their crimes. Many DINA agents fled Chile to evade justice, finding safe haven in other countries that had participated in Operation Condor. In the 1990s, Chilean detectives seeking those fugitives collaborated with intelligence officials from other Southern Cone countries to carry out Operation Casualty Control, traveling to Brazil for Osvaldo Romo, Paraguay for Miguel Estay Reyno, and Uruguay for Eugenio Berrios. Romo was wanted for his role in the disappearance of 60 Chilean dissidents; Berrios, who was a biochemist, was recruited by DINA to create biochemical weapons. The fact that these men were not members of the military, Bonnefoy writes, made them “part of the weakest link in the dictatorship’s intelligence apparatus: civilian agents.”

The pursuit of justice was further complicated by the passage of time. The majority of the detectives investigating dictatorship crimes were too young to clearly remember the horrors of the early dictatorship era. Indeed, Bonnefoy describes the detectives’ approach as working on cold cases, despite the fact that the trauma of these crimes prevailed for many Chilean citizens. “For the relatives of victims and their descendants,” writes Bonnefoy, “the wounds from the past have still not healed, but for these detectives, investigating these crimes has meant digging up the past with threadbare, unreliable documentation and without fresh testimony or the ability to access the original scenes of the crimes.”

“Justice to the Extent Possible”

Bonnefoy’s narrative is deeply informative and engaging. The book’s vivid descriptions are interspersed with excerpts from interviews that Bonnefoy conducted with the detectives of the Investigative Brigade for Crimes against Human Rights, now known as the PDI, a unit within the PICH. These interviews shed light on the psychological trauma experienced by the detectives involved in the early investigations, a formerly overlooked issue resulting from the secrecy under which they were obliged to work and the complicated nature of investigating some of their own PICH colleagues. Meanwhile, Aylwin’s pursuit of “justice to the extent possible” exposed the limits of what the justice system and the democratic government could achieve, with Pinochet still a major influence in Chilean society and politics.

The book devotes considerable attention to the story of Luz Arce, a Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) member who later joined DINA after breaking down during her detention and torture in 1974. Arce’s testimony to the Rettig Commission was cited by the PICH as vital in helping to identify 47 DINA agents, among them Ricardo Lawrence who once poured boiling oil into a prisoner’s mouth during a torture session. Arce participated in 63 judicial proceedings against DINA agents, and her testimony alone provided the Rettig Commission with an organizational chart of DINA, helping detectives to weave together strands of information and identify other dictatorship criminals.

Bonnefoy’s research reads like a detailed behind-the-scenes narrative. She focuses on individual cases that help illustrate the bigger picture, digging deep into their backstories to bring to life a less documented period in Chile’s recent history. Bonnefoy’s text illuminates the lived experiences behind the pursuit of justice, and the sense of duty that inspired the detectives involved in bringing about a democratic transition still monopolized by the military.

Ramona Wadi is a freelance journalist, political analyst, and book reviewer specializing in South America and Palestine.