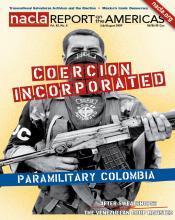

In May, the Colombian senate began deliberations on a draft law that would grant pardons to former paramilitaries, including those who had committed massacres. Moreover, it would allow them to run for public office, become public employees, or enter into government contracts. Those who have committed serious crimes could “receive full political rehabilitation and get more benefits than are normally given in laws governing amnesties and pardons,” warned Jaime Castro, a former Colombian government minister, speaking to Miami’s El Nuevo Herald. The reform was championed by Fabio Valencia Cossio, minister of the Interior and Justice, whose older brother happens to be on trial for belonging to the Bloque Élmer Cárdenas, a militia unit of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), once the country’s largest paramilitary organization. Such a brazen attempt at not only granting paramilitaries impunity but making them over as legitimate political actors bespeaks the extent to which these violent groups have infiltrated the Colombian body politic. As the sociologist Jasmin Hristsov explains in this issue’s opening piece, the government of President Álvaro Uribe began a “peace process” with the AUC in 2002 that, although farcical, has played an important role in creating the illusion of a paramilitary “demobilization” that in fact represents “the final, definitive incorporation of paramilitarism into the Colombian state and economy”: coercion incorporated.