The Mexico City metropolitan area is so enormous it almost had two time zones. In 2001, the head of the government for the Federal District, Andrés Manuel López Obrador—now Mexican president—refused to comply with President Vicente Fox’s proposal for daylight savings time. If this quarrel had not been settled, it would have been possible to gain or lose an hour merely by crossing the street in parts of the city that divide the Federal District from the State of Mexico. A Supreme Court decision prevented this confusion, but its prospect remains an apt metaphor for Mexico City’s vast heterogeneity. This is a place, writes Juan Villoro, where millions of people “live in millions of different ways.”

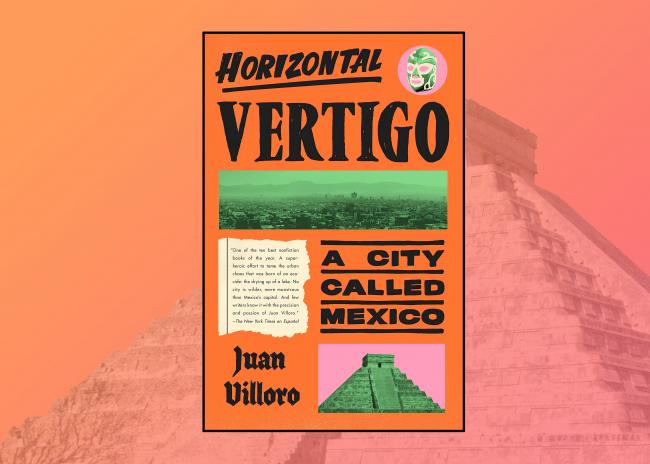

In Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico, Villoro, the acclaimed writer who helped draft the capital’s constitution, offers his interpretation of the Americas’ most extraordinary city, from Indigenous antiquity to the Aztec period, from the Spanish conquest to the present. The English translation by Alfred MacAdam was published this May by Pantheon, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Villoro, a newspaper columnist whose interests range from soccer to cinema, has won numerous Spanish-language prizes for his novels and journalism. His best-known work El Testigo is set in the aftermath of Mexico’s presidential election in 2000, when the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) lost power for the first time in 71 years.

In Horizontal Vertigo—which is comprised of 46 short chapters of essay, memoir, and travelogue—Villoro, a Mexico City native writes to capture the city’s spirit, humbly putting forward his “one interpretation among millions.” His title refers to the expansion of the city outward rather upward, to mitigate the threat of earthquakes.

Villoro guides the reader through vicarious travel, introducing us to characters such as the workmen who may or may not be unclogging his sewer, and the haughty store manager with his “offensive courtesy.” Omnipresent is Villoro’s protagonist—Mexico City itself.

As Villoro explains, what we understand of Mexico City’s past is part history, part myth. “According to legend,” he writes, “the Aztlán [Mexica] tribe left Nayarit, on the Pacific coast, and made its way to the central zone, crossing abrupt mountain chains. The Valley of Anáhuac opened before them like an unusual flatland surrounded by volcanoes, with a lake that provided water. The term high plain we use for our peculiar geography refers to horizontality at high altitude.”

The lake and the city’s nexus of canals that so astonished the Spanish are no longer there, but successive civilizations have proved unable to conquer the valley’s natural power, sometimes leading to tragic consequences. Although surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the main threat to the city is not the geography above, but the seismology below (especially since the Spanish built on the porous soil) and the humanity within.

A case in point is the high-rise area of Tlatelolco, which, Villoro writes, “acquired a tragic reputation in 1968, when the Plaza of the Three Cultures became the sacrificial altar where the student movement was repressed. Seventeen years later, it was one of the places that suffered maximum devastation from the earthquake.”

Horizontal Vertigo is at times a devastating critique of Mexico City’s political leaders and their top-down, or vertical, democracy. Of the 8.1-magnitude earthquake in 1985 that killed 10,000 people, he writes: “the earth carried out the scrutiny the government would never conduct.” A generation later, it took the H1N1 epidemic of 2009 for the government to realize 50,000 of the capital’s schools lacked running water. Villoro’s final chapter, a moving reflection on the 2017 earthquake, criticizes the real estate speculation that means “buildings over twenty stories are being constructed on terrain softened by mud and subject to seismic shifts.” Construction is allowed, says Villoro, because of the “economic benefit urban developers reap and the resulting support they contribute to those who govern the city and hope to govern the nation.”

In his essay ‘La Independencia, S.A. de C.V.’—one of his best—Villoro describes how the mythology of a Mexica past and the barbarism of colonial rule are used by the government to justify national failure.

“In our schools Independence is taught as a strange return to origins: we were pure Mexicans, we ceased to be that during the Conquest, and we became pure Mexicans again when the Dolores church bell rang out. This ultrapatriotic vision of our origin has had the ideological function of rationalizing our failure. NASA is not in Mexico because the conquistador Pedro de Alvarado slit the throats of the native astronomers. In official discourse, the Conquest serves as a pretext for justifying our bogged-down present.”

Villoro points out that mythologization pre-dates the Spanish conquest. According to the archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, after settling by Lake Texcoco, the Aztlán [Mexica] thereupon told the story that they were searching for a prophetic image of an eagle devouring a serpent, which they found by the shores of the lake. What’s more, Villoro writes, “To supply themselves with a foundation epic, they appropriated the mythic past of other people [who lived to the north], the Toltecs and the inhabitants of Teotihuacán. In the fifteenth century, the Mexica invent—a posteriori—the legend of their grandeur.” This process is ongoing. You could argue that, since independence, the mixed-race republic has appropriated the past of the Mexica.

Villoro’s best evocation of place is of Tepito, a neighborhood two kilometers north of the historic center, and famous for its contraband market. “If videos about Castoriadis and Heidegger are sold there it’s because someone will buy them. Should it happen that for some inexplicable reason something is not available, they’ll get if for you in a week.”

Villoro continues:

“Mexico City offers numerous surprises when it comes to the circulation of cultural goods. Out of nowhere, a vendor walks into your subway car and offers Aristotle’s Ethics: three people buy it in under two minutes. It’s true that doesn’t happen every day and that the next vendor has a loudspeaker strapped to his back broadcasting Shakira’s spasmodic lamentations, but there can be no doubt that one of the most peculiar traits of our urban life is the bootleg promotion of the most sophisticated culture. All this is to say that if one of the critics from Cahiers du Cinéma is missing a film by Raúl Ruiz, he’d find it in Tepito.”

Villoro’s prose often displays the influence of a long-time Mexico City resident, Gabriel García Márquez. Villoro describes his neighbor’s jumbled garden as a place “where the plants grew in the same disorder that swirled the hair of the owner.” Of his parents, he writes, “Both came from separatist traditions—he from Cataluña and she from Yucatán. So, it wasn’t at all odd that they separated when I was nine.”

Elsewhere, his darkly humorous eye is turned to observational comedy, such as his invective against the four-kilo books and the pens on string that buildings deploy in lobbies as a pretense of vetting visitors. Often, security officials won’t check the information provided against documentation, and Villoro suspects that “you can check yourself in as Joseph Stalin, Osama bin Laden, Marta Sahagún, or Rabina Gran Tagora.” The buildings distrust callers enough to ask them to perform a tedious task, but rarely do their security personnel do anything with that information that would ensure the building’s safety. As Villoro writes, “The book makes things difficult and that generates a control fantasy.”

Indeed, for Villoro distrust is “an essential feature of our national being: after sending an important email, we telephone to see if it arrived. And hypersensitiveness is another essential feature: if we’re invited to a party only by email, we’re offended.”

In this political, cultural, and social meditation, Villoro makes regular but short detours out of the megalopolis—to Kierkegaard’s philosophy, Joyce’s Dublin, and Borges’s Buenos Aires. Occasionally, the detours are the point of the chapter, such as in Shocks: New Meat, an acerbic essay on our dependence on technology. “When we’re asked for identification,” Villoro writes, “the decisive proof is not that the photo looks like us but that we look like the photo.”

As the recurring chapter names convey, Horizontal Vertigo’s themes are Shocks, Ceremonies, Crossings, Places, Living in the City, and City Characters. As Villoro says in his introduction: “The reader may follow from beginning to end, or choose, like a flâneur or subway rider, the routes that interest him most.” This democratic suggestion reiterates the author’s view that his book is “one interpretation among millions.” Horizontal Vertigo, like its city, can be read in multiple ways.

Well-informed outsiders with storytelling gifts can paint distinctive portraits of places, but nothing can compare with the insight of a well-traveled insider—especially when they write as well as Juan Villoro.

Horizontal Vertigo joins a long literary tradition of personal accounts of Mexico City. More rooted in the city itself than Francisco Goldman’s El circuito interior: Una crónica de la ciudad de México (2014), Horizontal Vertigo shares elements of social critique with J.M. Servín’s DF Confidencial (2010), and the wide range of subjects that characterized work of the popular essayist and activist Carlos Monsiváis (1938–2010). Villoro can say his is but one interpretation of the tumultuous megalopolis, but, now-published in the United States, Horizontal Vertigo could be the definitive English-language meditation on a city called Mexico.

Daniel Rey is a British-Colombian writer and historian.