Despite the consensus that criminal defamation laws violate international freedom of expression standards, archaic defamation provisions are being used to target investigative journalists across Latin America. This disturbing resurgence represents a danger to freedom of expression in the region and could deter the aggressive reporting necessary for robust debate in a free and open society.

A recent case in Peru, involving a prominent investigative reporter and an international publishing house, has sparked an outcry, including from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), the United Nations, the European Union, and the U.S., UK, and Canadian embassies in Lima.

On January 10, a Peruvian criminal court judge found Christopher Acosta, investigations editor at the private Lima broadcaster Latina Noticias, and Jerónimo Pimentel, editor of Penguin Random House Peru, guilty of defaming César Acuña, a former mayor, governor, congressman, and two-time presidential candidate. Acosta and Pimentel were both given two-year suspended prison sentences and will not serve prison time. The judge also ordered Acosta, Pimentel, and Penguin Random House Peru to pay Acuña a total of 400,000 Peruvian soles ($102,608) in damages, according to the sentence.

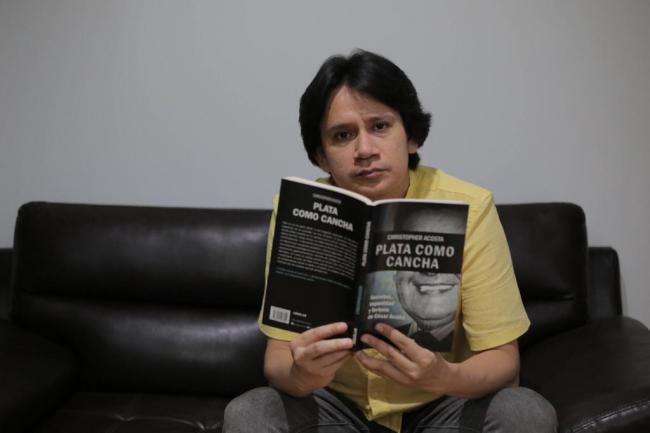

The charges stemmed from Acosta’s 2021 book, Money Like Popcorn: Secrets, Impunity, and the Fortune of César Acuña, which was published by Penguin Random House Peru. In the book, Acosta cited several public sources who alleged that Acuña was engaged in embezzlement, buying votes, and fraud. Of the 55 sentences that Acuña said he considered offensive, Judge Raúl Jesús Vega said 34 were defamatory and censured the journalist for not corroborating the allegations.

“Every single sentence [in the book] is supported by documents, interviews, and sources that are public and verified,” Acosta said.

International jurisprudence has found that public officials, because of their role, should be subjected to greater public scrutiny. The Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression, adopted by the IACHR in 2000, asserts that criminal defamation laws violate freedom of expression guarantees. And, according to international press freedom organizations, politicians and public officials are the actors who most often target and seek to silence their critics with these laws.

Acosta’s lawyer, Roberto Pereira, a well-known media freedom attorney, said the ruling “ignores that the plaintiff is a public figure who should have ample margins of scrutiny.” He said one of the most troubling aspects of the ruling was that the judge used an erroneous standard and showed no understanding of the “faithful or neutral reporting” doctrine, which is recognized by the IACHR in the case of Costa Rican journalist Herrera Ulloa in 2004. The doctrine applies “in those cases in which a communications medium is simply reporting statements made by third parties that violate the law […] honor, personal and family privacy and one’s good name.”

International human rights instruments and a growing body of international legal opinion clearly state that defamation laws can have a chilling effect on speech, obstructing the right to freedom of expression and the right to be informed. In a statement, the office of the special rapporteur for freedom of expression of the Organization of American States (OAS) said the ruling runs counter to regional standards on freedom of expression, causing “a significant intimidating and self-censorship effect.” The rapporteur said the decision affects not only those convicted but also the “entire press and Peruvian society.”

According to national press freedom groups in Peru, including Instituto Prensa y Sociedad (IPYS) and Asociación Nacional de Periodistas (ANP), criminal defamation prosecutions against critical reporters have grown increasingly common in a country where investigative journalists have uncovered high-profile corruption cases in recent years, which have landed four ex-presidents in jail. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a New York-based international press freedom organization, said in December that in 2021, “authorities in countries across the Americas, including Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, brought criminal defamation suits against investigative journalists, many of whom were reporting on allegations of corruption or misconduct by public officials.”

Acosta’s lawyer also provided important historical context to the fight against decriminalizing defamation in Peru.

In the 2000s, with Alberto Fujimori as president, scandalous tabloids (popularly known as prensa chicha, a name originating from drinks made from corn) became a central part of Peruvian culture, Pereira said. Used to destroy and smear the reputation of opponents, this style of sensationalist journalism has endured throughout the years. “It has made officials, politicians, businessmen, and public figures in general reluctant to make any changes in the penal code and eliminate prison terms for defamation,” he said.

Instead, the opposite happened. A new bill, introduced on January 17 by a group of congressmen of the political party Podemos Peru, seeks to increase prison terms for defamation from three to six years, Pereira said.

Acosta said he worries about the chilling effect the ruling could have not only among his peers but also within the publishing industry, as media houses could feel intimidated by the threat of facing criminal and civil penalties. “For me, personally, this is a huge distraction,” he said. “I am forced to hit pause on several projects to dedicate my time to review legal documents and defend myself instead of doing my job as a journalist.”

The journalist also described the judge’s arguments as “poor,” saying it revealed his “total lack of understanding” of journalistic work. He said his lawyer had filed an appeal, which will be reviewed by a three-judge panel court. He said he is optimistic that the conviction will be revoked upon appeal. “There should be more ample criteria among this panel of judges,” he said, “who are more experienced and should be knowledgeable about international freedom of expression standards.”

Acosta said that this is the first case of a journalist sentenced for defamation charges from writing a book since the 2005 conviction of British freelancer Sally Bowen. Bowen was convicted of criminal defamation and ordered to pay 10,000 Peruvian soles ($3,000 at the time) to businessman Fernando Zevallos in connection with her book The Imperfect Spy: The Many Lives of Vladimiro Montesinos. The judge also sentenced Bowen to one year of probation and restricted her movements both within and outside of the country. But an appeals court, citing technical irregularities, overturned the conviction, according to the Paris-based international watchdog Reporters without Borders (RSF).

Still, free speech activists and lawyers worry about the risks of such a decision in a deeply polarized political environment.

“Such an absurd ruling imposes serious limits to the basic work of investigative reporting and its ability to seek public and verified sources of information,” Pereira said. “This is a dagger for investigative journalism in Peru.”

Carlos Lauría is a journalist and an international press freedom expert. He is the former head of the freedom of expression portfolio of the Open Society Foundation’s program on independent journalism, and director of regional programs and the Americas program at the Committee to Protect Journalists.