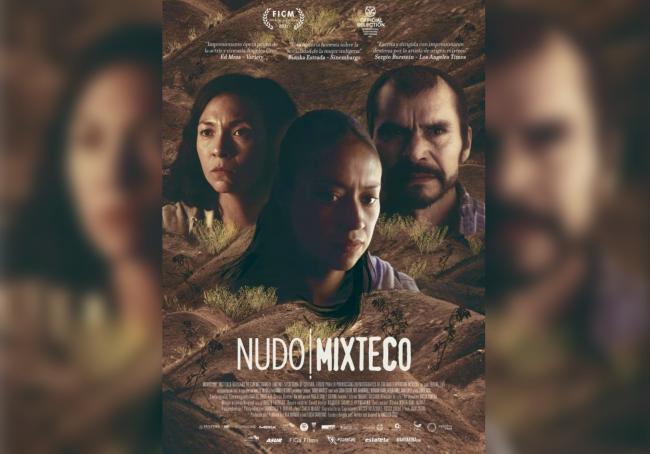

After several decades in film as a celebrated actress, Ángeles Cruz knew that she had something unique to offer as a storyteller and director. Her first three shorts—La tiricia o cómo curaré la tristeza (2012), La carta (2014) and Arcángel (2018)—all of which she both wrote and directed, were moving, award-winning pieces. With Nudo Mixteco, Cruz premieres her first feature-length original screenplay, earning her the 2022 Ariel Award for Best Feature Film Debut from the Mexican Academy of Cinematographic Arts and Sciences.

Nudo Mixteco, which translates to "Mixtecan Knot," takes us to the fictionalized town of San Mateo in the highlands of the Mexican state of Oaxaca, where three different narratives about female sexuality and machismo, generational violence and trauma, and the dynamics of poverty in a small community intertwine and overlap. Each distinct thread of the story appears separate at first, but Cruz masterfully weaves them into a rich multi-dimensional tapestry of life in this Mixtec town.

Untying the Knots

We are introduced first to Maria, a domestic servant in Mexico City, as she receives news of her mother’s passing and returns to San Mateo for the funeral. A teary Maria arrives to pay her last respects but is shunned and rejected by her father, who cannot forgive her for her sexuality—her love for other women. He blames Maria’s sexuality for her mother’s death. Maria seeks solace with a former lover, Piedad, a woman who is now a single mother of an infant.

Next, we meet Chabela, a mother of two, who has been struggling with the absence and neglect of her husband, Esteban. Esteban left to earn money as a traveling musician for a year, but has been gone for three. He expects a warm homecoming but instead spends his first day drinking so much that he falls asleep on a stoop next to the town plaza, and doesn’t seek out Chabela and his children until the following day. It is then that he discovers that she has moved on in order to fill the gap left by his absence and becomes enraged, demanding a community hearing to decide their fates.

Finally, we see Toña, an independent woman who runs her own stall selling goods in an unnamed city, and sends money back for her daughter in San Mateo. When her daughter calls, Toña knows immediately that something is profoundly wrong. She returns to her hometown, where we learn the horrible reason she was forced to leave in the first place. Cruz subtly builds the intensity as she depicts Toña’s overdue fight against the family hierarchy to protect her daughter from the same relative who abused Toña as a child, and who her own mother still staunchly defends, despite knowing what he did.

Cruz, who is of Mixtec origin and grew up in the rural highlands of Oaxaca, is intimately familiar with the landscapes of Nudo Mixteco, and this shows in her portrayal of the characters and their everyday lives. The beauty and sometimes hard reality of the setting is shown in the folds of the bare hills outside town where Maria and Piedad talk, the gnarled roots on the banks of the stream where Toña and her daughter sit, and the unpresuming but cared for interiors of each home, though none of these is glamorized or dwelled upon. The sights and sounds of the film have an earthy texture that brings to life the complexity of each character, even when no words are uttered.

“I think that language alone is not the key,” said Cruz in an interview. “For me, the dialogue is only one part of the narrative, but it is not the most important thing. The most important thing is what happens around it, what happens inside your habitat, what happens in the silences.”

Cruz pulls the viewer into the lived reality of each character without being overly demonstrative. The camera doesn’t linger, but the viewer can’t help but notice the texture of fabrics, the quality of light, the ambient sounds of the town. This makes the story of each protagonist feel familiar and relatable, even if the world they inhabit is foreign to the viewer. These characters are individuals with secrets and inner lives, but they are also members of a community, and their lives overlap with one another in a way that the structure of the film beautifully echoes.

Throughout the film, we become aware that instead of a linear progression of events, each of the three stories is unfolding simultaneously. Toña and Esteban return to San Mateo on the same bus, the call to Chabela’s trial is audible in the background while Maria talks to Piedad in the hills, and the funeral procession for Maria’s mother passes by Chabela’s trial. Though they exist in the same community, each person is too absorbed in their own story to clearly see the parallel realities around them.

Deconstructing Taboos

The themes of visibility and autonomy, which resurface throughout the film, appear in the opening plotline of Nudo Mixteco. Cruz explained that the need to tell Maria’s story arose from conversations she heard in her own town that denied the existence of lesbian love within Indigenous communities.

“I heard it said that in my community there were no lesbian women, that they did not exist there. Hearing that conversation obligated me to talk about their existence,” Cruz said.

Cruz is keenly aware of the sexism and homophobia that exist around the world, but explained that “in the case of Mexico, talking about lesbian women in Indigenous communities is particularly complicated and difficult due to the tremendous machismo that exists in the country.”

The scenes of Maria and her lover Piedad are easy and familiar. The intimacy shown on camera has none of the pretend sexiness of Hollywood, and more importantly, none of it is shown for any kind of synthetic shock value. Unlike many films in which forbidden love is a focal point, no great tragedy or dramatization occurs. Their relationship is not unrequited, predatory, idealized, or a matter of life and death; it simply is, in the multifaceted way that heterosexual relationships are allowed to exist on screen.

Though she finds solace with Piedad, Maria is haunted by a feeling that she doesn’t belong in San Mateo. “I think that this happens to all of us who migrate,” said Cruz, “we have a very strong bond with the community, but we don't know how to behave when we return to that place either. We don't know how to get out of there, how to return there, and in this construction of our new identities I believe that humanity is stuck.”

Maria’s internal turmoil about where she belongs is that of anyone who has been forced from their home. It is an internal forced migration, a theme that recurs in each of the three plotlines, and throughout modern-day Mexico.

The second story, though told from Esteban’s perspective, is not actually about him. The viewer is more inclined to empathize with Chabela, and Cruz knows this. She intentionally tells the story through Esteban to avoid romanticizing either perspective, and to give Chabela the opportunity “to fight for that small space, to decide her own territory, which is the body.”

Cruz doesn’t make this fight easy or unambiguous. “We see the reasons for each person’s dilemma”, Cruz said. She tries to look at each character and examine their point of view, weaving all of the questions she might have about that perspective into the story. She explains that it is “a way of approaching cinema through questions that come from my heart.” This approach allows the viewer to muster empathy even for characters like Esteban, who had a hand in his own undoing.

Toña, like the other women in Nudo Mixteco, is forced to sever familial ties to end the cycles of abuse that are now affecting her traumatized daughter. Cruz captures the uncertainty about the future in a touching scene between mother and daughter by a creek, a setting of hope and a chance at recovery.

Re-Writing the Narrative

Each of the three main characters in Nudo Mixteco were forced to leave the community for different reasons. “In my community there is a lot of migration,” Cruz said. “Families are divided: the father in one place, the mother in another, sometimes the children are left in the care of the grandmothers or the grandfathers.” We see this in every family shown in the film, and in the uncertain nature of their futures.

“I don't resolve, I don't give answers,” said Cruz about the way she chose to end the film. “I don't know how they're each going to come out into the world but they will come out differently. I believe that as people, when we decide to untie what ties us to the past, or face these pains and confront things, we don't really know where we are going. We just know that we are taking a step to get out of there.”

Nudo Mixteco is a deeply personal project for Cruz, not only because of who the protagonists are, but because the film is a deep dive into her artistic self-awareness in a Mexican film industry that tends to perpetuate tropes, recycle stories, and pigeonhole non-white artists.

When Cruz started out as an actress in the early 1990s, she was cast as the stereotypical Indigenous character in various film projects. “[I was] always being portrayed negatively through characters that were destined to serve, and I feel that this generates a reference within our collective unconscious,” Cruz said. “We think that we can only aspire to do that, that we cannot become presidents of the republic, heroines.”

For Cruz, her own rupture from that industry straitjacket came with a desire to, if not break, at least restructure the ossified tenets of the Mexican film industry by fleshing out and humanizing the everyday complexities and generational traumas affecting individuals from historically marginalized communities. Cruz’s journey from being cast as a racialized, two-dimensional character to her self-actualization as a filmmaker in her own right is a testament not only to her resilience, but her visionary, taboo-shattering talent. Nudo Mixteco represents Cruz finally at the lead of her own creative processes, one that has the potential to shift the narrative of Mexican cinema.

“It’s about how we as contemporary Indigenous women can decide on the use of our bodies,” Cruz emphasized. “In that sense, I felt that I needed to change, to move. It was my foray into scriptwriting and directing.”

In the opening credits of Nudo Mixteco, a poem appears: “I felt that I did not belong to this world, I fantasized that I was flying, that one day I was going to disappear and turn into rain, but time went by, I realized that I could not escape.” Nudo Mixteco is about that realization that one can’t simply escape the place they come from, and that no action exists in a vacuum.

Though uncertainty looms over Maria, Chabela, and Toña’s futures, the decisiveness of their actions says in no uncertain terms that they are going to “fight for that small space,” the body, which, as Cruz shows us, is everything.

Madeline McSherry is an environmentalist and visual artist currently based in Mexico City. A McGill graduate, she has spent the last decade working on conservation projects around the world, and has lived and worked in Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic.

Humberto J. Rocha is a reporter currently covering the European carbon markets and a freelancer focusing on politics and culture in Latin America. A Mexico City native and a Harvard and Oxford graduate, Humberto has written for local, national and international outlets.