This piece appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

In 2021, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, industry promoter Jon Barela testified at a joint hearing of the Texas House. CEO of the Borderplex Alliance—an El Paso, Texas-based economic development organization representing the leading voices of the maquiladora, construction, and fossil fuel industries on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border—Barela spoke at length about “an incredible, maybe once in a generation opportunity.” He was referring to the benefits of nearshoring—a term used by pundits, journalists, and government actors to refer to the relocation, or return, of manufacturing from China to the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

Barela and his associates hope that these relocation efforts will target the “Paso del Norte region,” a historical moniker local elites use to refer to the binational region encompassing the cities of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. He predicted a coming wave of nearshoring—“at least 100,000 jobs to the border region if we play our cards right”—due to the borderlands’ longstanding importance as a major manufacturing hub.

Ciudad Juárez, the birthplace of the maquiladora in the 1960s, is densely packed with (mostly) foreign-owned factories where goods are manually assembled for export, mainly to U.S. markets. In his testimony, Barela linked nearshoring to transnational corporations’ efforts to reduce transportation and labor costs and to combat supply chain disruption. This, he argued, was particularly important in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, which saw companies scrambling to fulfill orders as factories shut their doors during the pandemic’s onset.

In his remarks, Barela also highlighted geopolitical tensions between the United States and China as a driver of the coming “return” of manufacturing to the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. He argued that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s revival of the “common prosperity” concept in 2021 has amounted to “a return to Maoism.” “For that reason,” he said, “businesses are getting scared, and they are looking at very much returning to North America for manufacturing and other investments.”

Barela’s invocation of Maoism is representative of a wave of anti-China rhetoric leveraged by pundits and politicians in the United States, where transpacific economic competition has become increasingly wedded to a haphazard reignition of Cold War lingo. In this context, the movement of manufacturing from China to the U.S.-Mexico borderlands is depicted as a national security concern or political imperative, de-linked from the ongoing restructuring of global supply chains by transnational corporations seeking to lower production costs.

This rush to repaint the latest reshuffling of supply chains in security terms has emerged at a time of unprecedented border militarization in the name of controlling migration. The El Paso-Ciudad Juárez region serves as both a leading destination for new factory expansions as well as an open-air laboratory for increasingly restrictive forms of border enforcement, migrant detention, binational military build-up, and technological surveillance.

The borderlands’ historical transformation into a hub for export-manufacturing is key to understanding the entangled relationship between nearshoring rhetoric and processes of border militarization.Today, the maquiladora is often framed as a product of 1990s neoliberalism, its boom linked to the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. But tracing its origin to the late 1960s in Ciudad Juárez—alongside the global boom in Export Processing Zones (EPZs) at the height of the Cold War—reveals how the maquiladora developed within a context of geopolitical struggle, northward migration, global anti-communism, and the creation of safe havens for corporate investment within highly militarized industrial corridors.

Excavating this history allows us to understand how border militarization is key to the economic the competitiveness of the borderlands as a manufacturing center, while also enhancing control over a region that is geopolitically important to U.S. economic interests and the reproduction of capital on a global scale.

The Maquiladora and Cold War Militarism

Mexico first announced its plan to allow foreign manufacturers to open export assembly plants in border cities in May 1965. Visiting Ciudad Juárez to announce the new industrial policy, Mexican Secretary of Industry and Commerce Octaviano Campos Salas promised miracles, ranging from the eradication of unemployment in the region to the literal “salvation of Ciudad Juárez” via foreign investment.

The new industrial policy, eventually called El Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza (Border Industrialization Program), designated a 20-kilometer strip just south of the geopolitical border as a tax- and duty-free zone for the “importations of raw materials, parts, components, machines, tools, equipment, and everything needed for the transformation of processing, assembly, and finishing products to be entirely exported.”

The plan effectively transformed the entire U.S.-Mexico border region into an early Export Processing Zone (EPZ) prototype. Ciudad Juárez was designated as the program’s pilot city.

Mexico was not alone, however, in its turn toward foreign investment and export processing as an economic development strategy. The 1960s saw a wave of EPZs established in countries with friendly relations with the United States, particularly in East Asia, where stalwart Cold War allies like Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines, and South Vietnam established EPZs during the mid-1960s through the early 1970s.

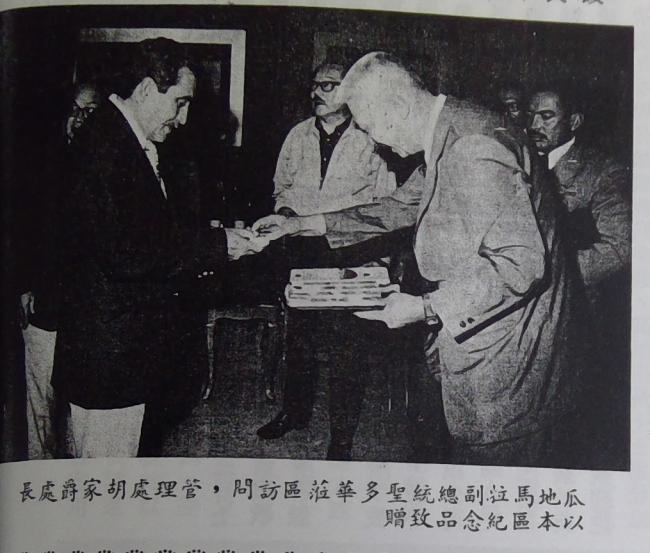

Taiwan was at the vanguard of this tendency, establishing its first EPZ in 1966. Proponents argued that the EPZ would attract foreign investment that could slowly contribute to a domestically controlled industrial base. Taiwan christened the zone as an “investor’s paradise” due to its disciplined workforce, strike-free labor environment, and favorable tax concessions to U.S. and Japanese firms.

Aside from pushing industrialization, Taiwan’s authoritarian government also used the EPZs as a strategic means to maintain its position as a Cold War anti-communist ally. For example, Taiwanese EPZs became important recipients of manufacturing contracts for uniforms and military goods that directly supported the U.S. war in Vietnam. More broadly, East Asian EPZs functioned as important material and ideological conduits for the promotion of export processing among U.S. Cold War allies. EPZs were not merely a lever of regional economic development. They also became a vehicle for global anti-communism, a facilitator of U.S. military efforts via manufacturing contracts, and a safe haven for U.S. capital in an era of global revolutionary upheaval.

Similar dynamics soon emerged in Mexico’s borderlands as the region transformed into a hub for export-assembly and a militarized industrial corridor.

A New Industry Takes Hold in Ciudad Juárez

In the maquiladora industry’s first 15 years of existence, industry promoters framed intensifying social movements in Ciudad Juárez and insurrectionary struggles in and beyond the borderlands as a serious security liability for regional industrialization plans. Four months after the inauguration of the industry in Ciudad Juárez in 1965, the militant left-wing Grupo Popular Guerrillero launched an assault on a military barracks in Madera, Chihuahua in an effort to ignite a popular socialist uprising throughout rural Chihuahua. Although the insurrection was quickly crushed, it inspired subsequent armed formations in northern Mexico, sparked anti-communist paranoia in the border press, and prompted a wave of counterinsurgency military campaigns.

The maquila industry became locked into struggle with social movements and frequently bemoaned the actions of Marxist groups and rising worker militancy in the local press.

Undoubtedly, social movement militancy in the borderlands in the 1970s, including student and factory worker organizing, damaged the border region’s early aspirations to become an “investor’s paradise” on par with Taiwan’s EPZs. Early maquiladora booster Richard Bolin reflected that, initially, few U.S. manufacturers saw promise in Mexican border cities, preferring the political security offered by authoritarian regimes in East Asia.

In the late 1970s, a combination of shifting global economic conditions, crackdowns by the Mexican army, and intensifying border militarization resolved these problems. First, successive currency devaluations meant wages in Mexican border cities became more competitive—as in cheaper—than in East Asia. At the same time, government-affiliated Mexican trade unions mobilized their cadre to crush wildcat strikes and intimidate independent organizers in factories. Increasingly favorable conditions in maquiladoras arguably prompted the first wave of nearshoring, as U.S. and Japanese manufacturers began to seriously consider Mexican border cities as attractive alternatives to their operations in countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

Second, the Mexican government’s Dirty War targeted the armed left, which led to the torture and disappearance of thousands of young activists. Although Guerrero was an epicenter of the reign of state terror, the counterinsurgent crackdown also liquidated armed leftist militancy in border cities.

Third, a wave of bipartisan policies in the United States leveraged an unprecedented level of military and economic resources to “secure” the border. Early forms of what we identify today as border militarization—the use of military tactics and equipment and the presence of military personnel—were characterized by increasing collaboration between the U.S. military and border patrol and the use of military technology for immigration enforcement and surveillance activities.

Together, currency devaluations, corporatist union intimidation of independent organizing, counterinsurgency, and early forms of border militarization were key to quelling labor militancy and social movement unrest in the borderlands, shutting down social dynamics that threatened the maquiladora industry’s ability to attract foreign investment to Ciudad Juárez.

Read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time.

Nina Ebner is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at CEDUA, Colegio de México. She has a PhD in Geography from the University of British Columbia. Her research focuses on processes of labor devaluation in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

Gabriel Antonio Solis is a PhD candidate in International and Global History at Columbia University. His research focuses on the comparative history of labor in export-assembly plants in Taiwan and the U.S.- Mexico border.