Leer este artículo en español.

The triumph of leftist Gustavo Petro and his vice-presidential running mate, Afro-Colombian environmental activist Francia Márquez, in Colombia’s presidential elections marks an unprecedented historical change. Their win with the Pacto Histórico movement represents a victory for long-sidelined social groups that have become the electoral majority in the country for the first time: a “periphery” composed of the Caribbean and Pacific coasts and the Amazon, as well as some major cities. Among their supporters are many Afro-Colombian and Indigenous groups. On the international level, Petro and Márquez’s victory has shaken what remained of the United States’ comfort zone in Latin America, which will allow the already significant majority of progressive governments in the region to strengthen their political alliances and push back against U.S. interventionist policies.

The complex situation in Colombia, however, could weaken the impact of this historic win. The new leaders inherit a country where the state, in practice, lacks a monopoly on the use of force and where fragmented criminal groups proliferate. The military is viewed with suspicion after army chief Eduardo Zapateiro took a political stance against Petro during the campaign. The country’s institutions remain closely tied to and influenced by the conservative and liberal currents of the traditional establishment, which will attempt to torpedo any significant change and block new initiatives. Petro and Márquez also face a divided Congress.

These concerns are sobering. But for the moment, and while the honeymoon lasts, the new president’s uncontestable victory and his opponents’ recognized defeat leave him much room to maneuver.

Redrawing the Electoral Map

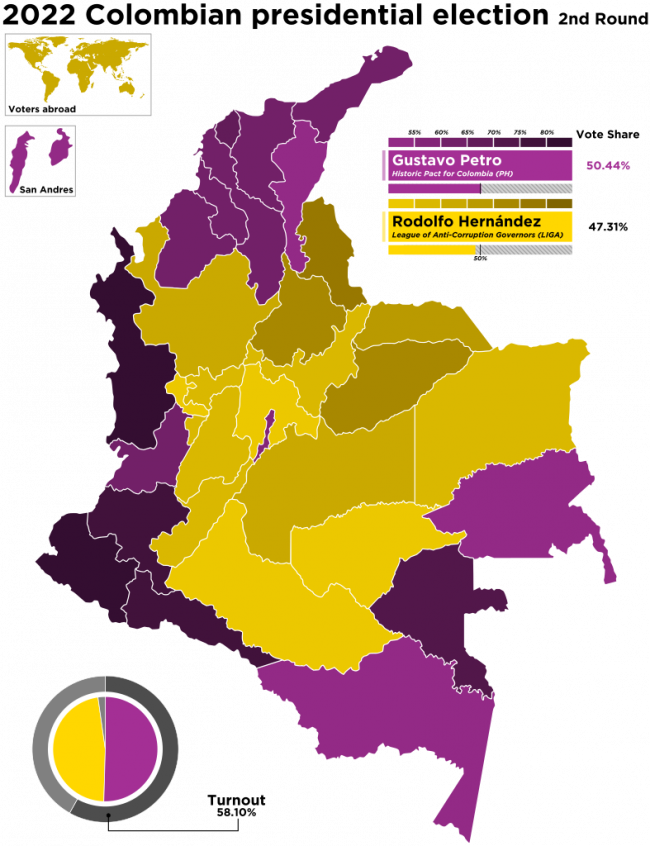

Petro was formerly part of the M-19 guerilla group, mayor of Bogotá (2012-2015), and a senator. A two-time failed presidential candidate, he has become a leading voice in the movement for peace and a spokesperson for popular demands. His running mate, Márquez, is an Afro-Colombian leader from a small mining town. Building on her activism in her home department of Cauca and her work in recent years as part of nationwide protests, Márquez joined the national political stage as a defender of environmental and women’s rights. Petro and Márquez are part of the Pacto Histórico, a collective of leftist and progressive individuals and movements. Their progressive and environmentalist proposals won the election with the most votes in Colombian history—more than 11 million—beating businessman and civil engineer Rodolfo Hernández by more than 700,000 votes.

This victory broke former conservative president Álvaro Uribe’s hold on the country, ending years of Uribista victories and significant abstention rates. As the dominant political movement of the last two decades, Uribismo has swept elections. Its founder and leader, ex-President Uribe (2002-2010), is known as the leading proponent of a militarized response to the armed Left. Aside from his eight years as president, he has greatly influenced the electoral results in the past decade, including the rejection of the peace accords at the polls in 2016 and his protégé Iván Duque’s victory in the 2018 presidential elections.

Uribismo has been not just an electoral machine but also a war machine that, with the complicity of the “international community” and global media, has produced a trail of violence, from the false positives scandal under Uribe’s reign to the ongoing assassination of social leaders and signers of the peace accord, massacres, forced disappearances, and unearthing of mass graves. All this with the goal of maintaining power and holding off the subversive groups, especially the FARC. During Uribe’s tenure, the state succeeded in significantly decreasing the number of FARC fighters, killing top FARC commanders, and freeing many hostages. These achievements received high praise from the centers of global power, particularly in Washington, which in recent decades made Colombia the bastion of its backyard, its beachhead in the region.

When Uribe was at his peak in the 2006 elections, he won handily but with voter turnout at just 45 percent. In contrast, in the second-round presidential election on July 19, 58 percent of the population voted—record-breaking participation in this century—after 54 percent turnout in the first round. Abstention decreased precisely in the territories where Petro and Márquez have the most influence: on the Pacific and Caribbean coasts and in big cities. This is an epic accomplishment. Amid significant violence and criminalization and despite constant negative news coverage, Petro managed to mobilize Colombia’s “periphery” and disrupt Uribismo’s dominance in the conservative parts of the country, especially Andean regions.

It is no coincidence that Petro is the first Colombian president to hail from the coast and that Márquez is the first Afro-Colombian vice president, as a map of electoral results makes clear. The central Andes supported Hernández, a populist center-right millionaire who the establishment rallied behind in the second round. Support for Petro, came, in addition to the capital, from the edges—the frontiers if you will—of the Pacific and Caribbean coasts and the Amazon.

This radical turn is especially epic because it did not occur in peaceful times: in large part, the vote for Petro and Márquez came from regions where violence has increased. It is a protest vote against the established powers by those historically excluded, especially Indigenous people and Afro-Colombians who are often considered “less Colombian” in the conservative Andean tradition. This emerging cultural power is an act of disobedience against the historically powerful, many of whom are heirs of Uribismo and who were unable to stop the popular movement that swept the polls.

The Geopolitical Impact of the Left’s Win in Colombia

Over the last 20 years, Washington made Colombia an outpost that included bases, armories, and the strong presence of branches like the CIA and DEA. With military aid, extraordinary funds, and alliances with proponents of war, the United States sought not only to eradicate the Colombian guerillas but also to bring to a halt the progressive processes in neighboring Venezuela and the rest of Latin America.

Plan Colombia, the bilateral agreement between the United States and Colombia launched in 2000 in the name of combatting armed leftist insurgencies and drug trafficking, amounted to the largest U.S. investment in the region of the last several decades. Between 2000 and 2005, the U.S. government pumped $4.5 billion into Plan Colombia. Other sources put the figures closer to $10 billion between 2001 and 2016. Today, U.S. political, military, and financial intervention in Colombia continues.

These years-long U.S. efforts are now suspended, as the latest election represents a change in direction. This change has long been brewing, as seen in the waves of social uprisings that swept the country in 2018, 2020, and 2021; the defeat of Uribismo at the polls in the 2019 regional elections and in the March legislative elections; and Uribe’s resignation from the Senate and his two-month-long house arrest in 2020. Even though the polls predicted Petro’s victory, the official result is still surprising.

Petro’s Challenge

The Colombia that Petro has inherited is a multidimensional and complex mess of issues, each more explosive than the last. Drug trafficking is one of those issues. Currently, Colombia is the world’s largest producer of cocaine, and its production is growing, with increasing efficiency.

In June 2021, the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy annual report on cocaine production documented a record increase of nearly 15 percent in Colombia in just one year. In April 2019, then-president Donald Trump blamed Colombia’s now outgoing president, Duque, for the increase in drug exports.

Meanwhile, the demobilization of guerillas and paramilitaries that followed the peace accords and other negotiation processes has ended up increasing violence and wrenching control of vast territories from the state. Two recent events illustrate this latent threat. In May, the Clan del Golfo paramilitary group paralyzed a large part of the country to protest the extradition of their leader, alias Otoniel, inflicting violence on at least 17 towns across 11 departments. And in February, the National Liberation Army (ELN) launched a so-called paro armado or guerilla-enforced economic shutdown that required a military response in at least 11 departments.

Amid all this, it remains to be seen how Petro will interact with the military, religious institutions, and the media—sectors that have actively confronted him. He will also have to navigate relations with the autonomous state institutions that ousted him from the mayor’s office in 2014.

Petro is no political novice. Now anointed with popular legitimacy, he has said, “if we are isolated, we will fall,” referring to the Left’s need not to radicalize, but to open itself to conversation with those of different views, including conservatives. He faces a complex, multidimensional, and explosive situation. But at the same time, he has the experience and the knowledge to manage the transition towards a post-war and post-Uribista Colombia that is now emerging in the wake of the peace accords and changing the country’s political map.

For now, Petro can count as a point for his side that he and Márquez accomplished a feat that only a few months ago seemed no more than a dream: a victory for Colombia’s popular and excluded people.

Ociel Alí López is a political analyst, professor at the Universidad Central de Venezuela, and contributor to various Venezuelan, Latin American, and European outlets. His book Dale más Gasolina won the municipal literature award in social research.