The following book review was published in the Spring 2012 issue of the NACLA Report on the Americas, "Central America: Legacies of War."

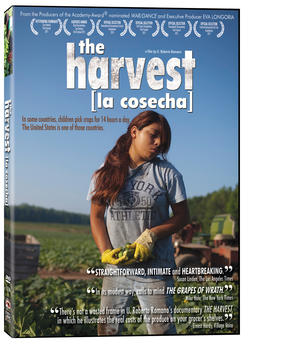

The Harvest (La Cosecha), directed by U. Roberto Romano, 2011, 80 mins., Cinema Libre Studio, theharvestfilm.com

U. Roberto Romano’s 2011 documentary The Harvest (La Cosecha) reminds us of the human cost of what we eat. “In some countries, children work 14 hours a day, seven days a week,” he explains in the film. “In some countries, children 12 and younger pick crops. The United States of America is one of those countries.”

Romano’s documentary compels viewers to come to terms with the uncomfortable reality that in a country like the United States, where there is so much wealth, modern cities, and plentiful resources, many people still endure inequality and poverty.

The Harvest begins with the testimonies of three children. “I pick strawberries, cherries, pickles, and oranges,” says a young girl. “I just wanted to vomit ’cause [of] the sun and smell of tomatoes,” says a teenage boy. “The cotton plants when I was 10 looked like skyscrapers,” says another teenage girl.

We soon find out that the voices of the underage workers belong to the child migrant farmers Zulema López, 12; Víctor Huapilla, 16; and Perla Sánchez, 14. The documentary profiles the lives of these children and their families on the fields, as they migrate from harvest to harvest across the United States.

Romano’s film underlines the fact that every year, over 400,000 children pick the food that we eat in 48 states. These children often come from multiple generations of migrant farming, and their families are unable to break away from the cycle of poverty.

“Why don’t we have any money?” asks Sánchez. “Because we can’t finish school.”

Many migrant children can’t finish high school because their financial dependence on the harvest season forces them to leave early, hindering their ability to study and get good grades. López’s mom explains how she was similarly trapped by this cycle and hopes that her children can aspire to a better life.

“When I was little, my dreams were to finish school, go to college,” she says. “Now that I couldn’t do that, I want my kids to be something in their lives. I tell them, you know, I don’t want to see you guys like me.”

For many migrant families, education is the only way out. But for someone like López, who started picking crops at seven years old, dedicating herself to school is unrealistic when she is also laboring long hours on the fields.

“I feel like I’m left behind,” López says, comparing herself to other students. “I don’t even think I am going to make it to high school or anything.”

According to Romano, migrant children drop out of school at four times the national rate. When the viewer sees that López typically wakes up at 4:30 a.m. on a workday, picks crops nearly 12 hours a day, and earns only $64 per week, it becomes clear that her difficult circumstances outweigh the prospects of getting a good education. Yet in spite of her hardships and ongoing insecurities, López is grateful that she is still with her family.

“Why is it suffering if I am not the only one who has to move?” she asks.

Many child farmers rely on their families as a source of stability.

“My inspiration is my family,” says Huapilla. He labors long hours on the fields so that his family can avoid any further hardships.

“I worked to help my parents when I saw they couldn’t manage,” he says. “Even though they never ask for it, I want to do it anyway.”

Huapilla gets paid $1 for every bucket of tomatoes that he collects. Each bucket weighs 25 pounds, and on a good day, he can carry over 1,500 pounds. Migrant children have no guaranteed minimum wage or overtime, and by the end of one shift, Huapilla’s hands are often blistered and rough. Soap alone won’t remove the thick layer of tomato juice and dirt that sticks to his skin, so he has to use bleach to scrub himself clean.

This sense of commitment compels the viewer to see Huapilla and the other children as the faces of the U.S. working class. Their plight personifies the hardships and sacrifices that most working-class families have to endure to remain together. During one rare moment in the film, we see Huapilla in school and get the sense that while his condition as a migrant worker is tragic, it can also be heroic in the context of his family. Huapilla’s teacher describes how “ordinary people like us” could become heroes in small ways. And according to this definition of heroism, every fruit or vegetable that Huapilla picks is a courageous step that helps his family move ahead.

Other migrant children like Sánchez, however, face discrimination in spite of their sacrifices.

“Just because you’re brown, they think you are from Mexico,” she says. “They tell you to go back to Mexico, go back to where you came from, without them knowing that I was born here. Where am I supposed to go?”

Sánchez is put down constantly by people who blame her condition as a migrant, and her family’s poverty, on stupidity. But she defends herself on camera by reminding the viewer that being a migrant is not about having made bad choices. These migrants simply don’t have time to be anything else.

“Time doesn’t stop because you are doing this [picking crops],” says Sánchez. “Time doesn’t stop because you are migrating. Time goes, and if it goes, it goes faster.”

Yet no matter how antithetical these children’s lives are to notions of the American dream, their endurance, which stems more from stubbornness than resilience, makes them hopeful.

“I have a dream to become a lawyer,” says Sánchez. “I have a dream to help other people stop being migrants. I have so many dreams to help other people just like me.”

Romano’s film ends on an upbeat note, paying tribute to role models—an astronaut, the director of a brain surgery program, and a distinguished academic, among others—who had been migrant children and were able to escape the cycle of poverty. But for many viewers, the lives of these role models are clearly an exception.

Migrants will continue to live like indentured servants as long as U.S. society treats them with indifference. By empathizing with these people, we will understand that they are not too different from our own families—ordinary men, women, and children who are on a quest for a better life.

Arturo Conde is the Director of NACLA and a freelance journalist. Read the rest of the Spring 2012 issue of the NACLA Report on the Americas, "Central America: Legacies of War."