The following is the introduction to the Summer 2012 issue of the NACLA Report on the Americas, "Latin America and the Global Economy." The full issue is available here.

During the mid-1980s, I would travel from my home in Nicaragua to San Salvador, El Salvador, where I frequented the campus of the Central American University. At lunchtime we would exit the main campus gates to one of the city’s principal thoroughfares, the Autopista Sur, dotted by rustic locally owned restaurants serving El Salvador’s signature plate, pupusas. Today, there is not one pupusería outside the university gates. The skyline is instead blighted by an endless array of signs beckoning diners to all the well-known transnational fast food chains, from Burger King to Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken to Panda Express and Pollo Campero. This “McDonaldization” or “Warlmartization”—the globalization of what were once local and national retail sectors—has taken Latin America by storm. In the 10 years from 1990 to 2000, transnational supermarket and retail outlets increased their percentage of the Latin American retail market from 10% to 60%. By the 21st century, Walmart became Mexico’s largest private employer, controlling over half of all supermarket sales.

The new face of global capitalism is everywhere in Latin America, from the ubiquitous fast-food chains, malls, and superstores that dominate local markets in emerging megacities to vast new fields of soy run by transnational agribusiness, which has invaded the Southern Cone countryside; from sprawling tourist complexes that have displaced thousands of communities to the export processing zones (EPZs) that employ hundreds of thousands as low-wage workers for the global assembly line. Whole neighborhoods have been built with remittance wages sent by the tens of millions of Latin American emigrants who provide cheap itinerant labor for other regions in the global economy. New trading patterns now link Latin America commercially to every continent. An academic or journalist returning to research Latin America’s economy after several decades away would barely recognize the subcontinent, so vast has been the transformation of its political economy and social structure, as the region has been swept into capitalist globalization.

Earlier research on the global economy focused on the phenomenon of “runaway factories.” The EPZs or maquiladoras, with their telltale exploitation of young women, became a premier symbol of capitalist globalization. Maquiladoras are now major components of the Mexican, Central American, and Caribbean economies, and EPZs have spread as well to the Andean region and even into the Southern Cone. But the Global Factory has since been joined by the Global Farm, as Latin America’s agriculture has become an extension of the new transnational agribusiness, and by the Global Supermarket, as retail sectors have become globalized. As Brazilian economist Paulo Kliass discusses in this issue, Brazil has overtaken the United Kingdom to become the world’s sixth-largest economy—a powerful testament to the economic rise of Latin America in the Global South and the changing nature of the international order.1

Yet as capitalist globalization has unleashed a new cycle of modernization and accumulation in the region, it has had contradictory effects. It has transformed the old oligarchic class structures, generating new transnationally oriented elites and high-consumption middle classes that enjoy the fruits of the global economic cornucopia even as it has displaced tens of millions, aggravated poverty and inequality in many countries, and wreaked havoc on the environment. Those newly marginalized and dispossessed have been anything but passive, as several articles in this issue make clear. Social movements of all kinds have joined in mass grassroots struggles that have helped to push a number of governments to the left in recent years and are now challenging the whole paradigm of global capitalism.

*

Latin America’s integration into the new global production and financial system followed the collapse, in the wake of the 1970s world economic crisis, of the post–World War II development model in Latin America. This pre-globalization model of accumulation had been based on domestic market expansion, populism, and import-substitution industrialization (ISI), the growth of traditional agro-exports and other primary commodities, the creation of state sectors, a role for the state in guiding accumulation, and redistribution through corporatist and populist coalitions. This model began to unravel in the late 1970s, paving the way for the neoliberal model based on integration to the global economy.2 Diverse social forces and political movements clashed during the next two decades over what would replace the old model.

During those two decades, the mass movements, revolutionary struggles, and nationalist and popular projects of the 1960s and 1970s were beaten back by local and international elites. The tide turned against these projects in the face of the debt crisis that hit the region hard in the 1980s, by state repression, and U.S. intervention, and later, by the collapse of a socialist alternative. Behind all of this, globalization shifted the worldwide correlation of class forces away from nationally organized popular classes and toward a new transnational capitalist class and local economic and political elites tied to transnational capital. In the 1980s and 1990s, as the logic of national accumulation became subordinated to that of global accumulation, new transnationally oriented elites among the dominant groups in Latin America gained control over states and capitalist institutions in their respective countries, and used that control to push forward capitalist globalization and a new model of accumulation.

This new breed of transnationally oriented elites and capitalists forged a neoliberal hegemony, privatizing, liberalizing, deregulating, “flexibilizing,” and cheapening labor, and implementing fiscal austerity, free trade, and investment regimes that facilitated transnational corporate access to the region’s abundant natural resources and fertile lands. As the region integrated deeper into world capitalism, trade in goods as a percentage of the regional GDP increased from 10% to 18% from 1989 to 1999. Latin America had entered the global age of hothouse accumulation, financial speculation, credit ratings, the Internet, malls, fast-food chains, and gated communities.

Neoliberalism forged a social base among emergent middle classes and professional strata for which globalization opened up new opportunities for upward mobility and participation in the global bazaar. But neoliberalism also brought about unprecedented social inequalities, mass unemployment, the immiseration and displacement of tens, if not hundreds, of millions from the popular classes, as Sarah Kozameh and Rebecca Ray—investigators with the Center for Economic and Policy Research—discuss in this issue. The changes triggered a wave of transnational migration and new rounds of mass mobilization from those who stayed behind.

*

Globalization has ushered in a new model of capitalist accumulation in Latin America that has vastly restructured the region’s productive base, and along with it, transformed the class structure, the social fabric, political systems, and cultural and ideological practices. By the early 21st century, the “commanding heights” of accumulation were no longer the old agro-exports or national industry and their oligarchies but a new set of activities that were introduced starting in the 1980s, and that formed part of globalized circuits of accumulation. Six dynamic new activities, in particular, have come to dominate the region’s political economy and its articulation to the world economy over the past 30 years.

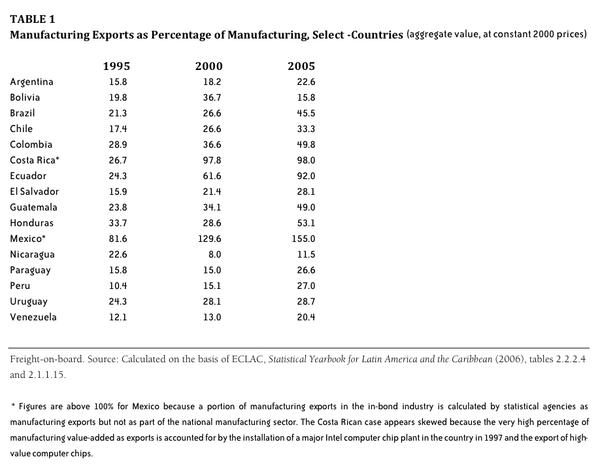

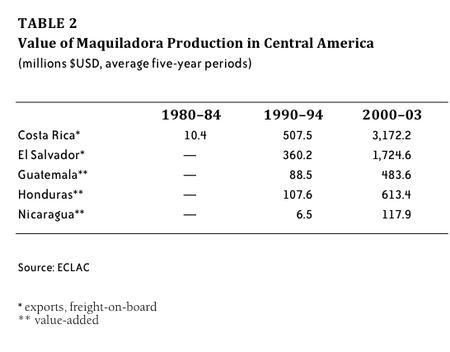

First, industry has been reoriented toward global markets with national industrial activity integrated into global production chains as component phases of the Global Factory. Most notable is the phenomenal spread of maquiladoras, which have been established along the U.S.-Mexico border since the 1970s and have subsequently spread throughout the greater Caribbean Basin and more recently as far south as Argentina and Brazil. Through this “industrial reconversion,” as it is known in international development discourse, small and medium-size industrial enterprises have also reoriented from the national to the global market by becoming local subcontractors and outsourcers for transnational corporations. Table 1 (above) shows the ongoing reorientation of industry into the Global Factory, and Table 2 (below) shows the explosive growth of maquiladoras in Central America from the 1980s into the 21st century.

Second, new transnational agribusiness exports have increasingly eclipsed the old agro-export and domestic agricultural models. Every national agricultural system in Latin America has been swept up in the new global agribusiness complex—the Global Farm. Alongside beef, coffee, and sugar, King Soy now dominates agriculture in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay. Soy is mass-produced and processed as industrial and edible oils, animal feed, and food for markets in Asia and elsewhere. Soy plantations set up by transnational agribusiness and run as capitalist “factories in the field” are displacing millions of small land holders, eating up the rainforests and savannas, and generating an ecological disaster. In Brazil, former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003–10) gave powerful support to agribusiness over small farms and the landless. In the countryside land ownership was more concentrated at the end of Lula’s term than it was 50 years ago. The countryside is “a landscape of endless seas of soy plantations, massive cattle ranches, and poisonous industrial farms that displace poor Brazilian families and cut down ever-larger swaths of rainforest,” observes writer Benjamin Dangl in his 2010 book, Dancing With Dynamite.3

In Mexico, millions of acres previously planted in corn, beans, and other crops for the domestic market have been replaced by fruits and vegetables for the Global Supermarket. Colombia and Ecuador are now the second- and third-largest exporters, respectively, of cut flowers to the world market. Chile’s Central Valley, once the country’s breadbasket, is now a specialized region for the intensive production and export of canned and fresh fruits and wines. The list goes on. This new face of transnational corporate agribusiness in Latin America involves capitalist rather than the earlier oligarchic or semi-feudal relations of production and draws in rural, often female, workers rather than the early peasant or peon labor.

Third, the growth of the global tourist industry has exploded over the last two decades. Virtually every Latin American country has been swept into the industry, which now employs millions of people, accounts for a growing portion of national revenue and gross national product, penetrates numerous traditional communities, and brings them into global capitalism. Local indigenous, Afro-descendant, and mestizo communities have fought displacement, environmental degradation, and the commodification of local cultures by tourist mega-projects such as the Ruta Maya in Mexico and Central America, the Ruta Inca in Peru, Punta Cana in the Dominican Republic, and San Pedro de Atacama in Chile. For many countries—including Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, and most of the Caribbean nations—tourism is the first- or second-most important source of foreign exchange. By 2004, tourism represented 12% of Latin America’s aggregate foreign exchange receipts, 33% for Cuba, 35% for the Central American republics, 35% for the Dominican Republic, 36% for Jamaica, and so on.4

Fourth, services, commerce, and finances have become increasingly transnationalized. The arrival of the Global Supermarket has involved the invasion of transnational retail conglomerates like Walmart, K-Mart, Costco, Carrefour, and Royal Ahold, as well as fast-food chains, as noted above, generally in partnership with Latin American investor groups. Fast-food chains, super-stores, and malls are the outlets for the distribution of goods from the Global Farm and the Global Factory. They have displaced thousands of small traders, disrupted local economies, and propagated a global consumer culture and ideology. Meanwhile, data-processing and call centers, outsourced from the Global North, have spread at an astonishing rate. Already by 2003, half a million Brazilians labored in call centers, largely women from 16 to 24 years of age, in what some characterized as “informational maquiladoras.”5

Latin America’s national financial systems have merged with what is now a single integrated global financial system. Transnational capital pours into the region as productive investment in the Global Factory, Farm, and Supermarket and also as portfolio and speculative financial ventures. These schemes take advantage of the bonanza created by the privatization of public assets, the deregulation of banking systems, and the issue of government bonds as a widespread mechanism in the region to attract investors from the money markets that dominate the global financial system. The global financial markets push countries to accommodate them and hold enormous power over states and social movements and their ability to transform society.

Fifth, labor has been among the major exports to the global economy. The wave of outmigration caused by capitalist penetration and disruption of local communities and of whole national and regional economies, and the social ravages of neoliberalism over the past few decades, is without precedent, comparable to migrations generated by war. Immigrant labor is exported across Latin America to intensive zones of accumulation and to the global economy, the United States, Europe, and beyond. In turn, this Latin American immigrant labor sends back remittances. Latin Americans working abroad sent to their home countries $61 billion in 2011 (down from a high of $70 billion before the 2008 crisis).6 Families receiving remittances have become integrated into a global retail sector that now controls over 70% of local retail markets. In other words, the social reproduction of millions of Latin Americans is dependent on these new global labor, financial, and commercial flows.

In many countries remittances are the number one source of foreign exchange ensuring macroeconomic stability, mitigating fiscal crises, and providing an escape valve for acute social and political tensions. In 2011, Mexico received nearly $23 billion in remittances, the country’s second-most important foreign exchange earner, after petroleum (if we don’t count drug money that enters the financial system, which is estimated at close to $35 billion). In most Central American and Caribbean countries, remittances outstrip the combined value of all other exports, and in several—El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, and Nicaragua—they hover at or above 20% of total GDP.7

Sixth, a new round of extractive activity has been launched, including a vast expansion of mining operations and energy extraction to feed a voracious global economy, especially in the Asia-Pacific region, as articles in this issue by political scientist He Li and economist Óscar Ugarteche discuss. Indeed, as Li points out, the Asia-Pacific region has displaced the United States as Latin America’s principal trading partner, and China is now the biggest foreign investor and lender in the region, much of its capital being invested in extractive activities and accompanying infrastructural projects. Ironically, a portion of this extractive expansion has taken place in the more left-oriented countries that have come to power in recent years, such as in Ecuador under President Rafael Correa or in Bolivia under President Evo Morales. These governments have used combinations of nationalizations, tax reforms, and social programs to redirect a portion of the income generated by extractivist activities toward poor majorities. What has been done in these cases is a reconversion from the old extractivism to a neo-extractivism, or 21st-century extractivism, in which the state has a larger participation in the rent generated by mining and oil, and there is a broader distribution of the income generated by these exports through social policy.8

The new face of global capitalism in Latin America is driven as much by local capitalist classes that have sought integration into the ranks of the transnational capitalist class as by transnational corporate and financial capital. Propelled by privatizations and liberalization during the 1980s and 1990s (and in some countries, into the 21st century as well), sectors of the capitalist class and the elite in Latin America amassed an unprecedented amount of wealth and power. They have merged with one another across borders into powerful grupos and conglomerates, known as multilatinas. In turn, these have cross-invested with extra-regional transnational corporations. According to one estimate, some 70 multilatinas are capable of competing worldwide in the global economy. Conglomerates like Mexico’s Telmex, Cemex, or Grupo Carso; Brazil’s Gerdau; the Cisnero dynasty in Venezuela; the Cuscatlán conglomerate in El Salvador; and the Argentine-based Grupo Arcor, among others, are full-fledged global corporations.9

*

The new model of accumulation described above has continued to deepen right into the second decade of the 21st century. But by the turn of the century, the neoliberal path of “development” was in crisis in the region. The new patterns of accumulation and the set of neoliberal policies that governments implemented to facilitate integration into global capitalism were unable to bring about any sustained development for a majority of the population, or even to prevent continued backward movement. The world recession of 2000–01 hit Latin America hard, undermining growth and reversing gains of previous years. Politically, the fragile democratic systems installed through the so-called transitions to democracy of the 1980s were increasingly unable to contain the social conflicts and political tensions generated by the polarizing and pauperizing effects of neoliberalism. The Washington Consensus eroded as the region experienced renewed economic stagnation. By the early 21st century, neoliberalism appeared to be reaching its ideological and political limits. The political turning point came with the collapse of the Argentine economy—previously the poster child of neoliberalism—and the subsequent mass uprising in 2001, which was followed throughout the region by a string of revolts among popular classes, an electoral comeback of the left, a new “radical populism,” the revival of a socialist agenda in Venezuela and elsewhere, and attempted coups and renewed U.S. interventionism.

The left-oriented or “pink tide” governments challenged and even reversed major components of the neoliberal program. Many of them halted privatizations, nationalized natural resources and other economic sectors, restored public health and education, expanded social spending, introduced social welfare programs, renegotiated foreign debts on discounted terms, broke with the IMF, and staked out foreign policies independent of Washington’s dictates. Those countries that stuck to the neoliberal path have been hardest hit by the crisis unleashed by the 2008 collapse of the global financial system. In their respective articles, Ugarteche and Kozameh and Ray highlight that those countries that have pursued post-neoliberal redistributive and regulatory policies, and limited re-nationalizations have fared much better, both with faster rates of economic growth and reductions in poverty and inequality. This process has been more advanced in South America than elsewhere in the region, where countries are also leading the push to develop alternative forms of cooperation and integration that break with political subordination to Washington’s dictates. In their article in this issue, sociologist R.A. Dello Buono and author Ximena de la Barra discuss these regional-integration efforts, most notably the recently founded Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). Clearly, the prospects for confronting the crisis of global capitalism must involve a deepening of these efforts.

Far from over, the international financial crisis is likely to heat up in the coming period. The IMF and other international economic agencies predicted sluggish performance in the global economy over the next year and likely recurrences of financial crises. Most informed observers agree that we are in the midst of a deep structural crisis, that neoliberalism is reaching its material and ideological limits, and that we are entering a time of great turbulence, conflict, and uncertainty in the global system. Structural crises of world capitalism are historically times of sustained social upheaval and transformation, as reflected in Latin America in the rise of pink tide governments and the resurgence of mass grassroots movements from below. As veteran Uruguayan journalist Raúl Zibechi discusses in this issue, these struggles are challenging not just the neoliberal model but the region’s very relationship to—if not participation in—world capitalism and the top-down models of elite domination, state authority, and decision making that remain in place, even in the pink tide countries. As Latin America becomes drawn ever deeper into the vortex of global turbulence, these struggles among distinct social and class forces over the nature and direction of change are sure to escalate.

William I. Robinson is Professor of Sociology, Global Studies, and Latin American Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara, and author of Latin America and Global Capitalism (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008). Read the rest of NACLA’s Summer 2012 issue: “Latin America and the Global Economy.”

1. Philip Inman, “Brazil Overtakes UK as World’s Sixth-Largest Economy,” The Economist, December 25, 2011.

2. For a summary, see A Theory of Global Capitalism (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), and for my major work on Latin America’s globalization, see Latin America and Global Capitalism (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

3. Benjamin Dangl, Dancing With Dynamite: Social Movements and States in Latin America (AK Press, 2010), 134.

4. For brevity’s sake, this data and all data not otherwise cited in an endnote are from Robinson, Latin America and Global Capitalism, various tables.

5. Ruy Braga, “Information Work and the Proletarian Condition Today,” Societies Without Borders 2, no. 1 (2007): 27–48.

6. Inter-American Development Bank, “Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean in 2011,” online report, Multilateral Investment Fund, available at idbdocs.iadb.org.

7. See table 3.15, in Robinson, Latin America and Global Capitalism, 162.

8. Carmelo Ruiz-Marrero, “The New Latin American ‘Progresismo’ and the Extractivism of the 21st Century,” Center for International Policy, Americas Program, February 17, 2011, available at cipamericas.org.

9. On these details, see Robinson, Latin America and Global Capitalism, 171–78.

Read the rest of NACLA’s Summer 2012 issue: “Latin America and the Global Economy.”