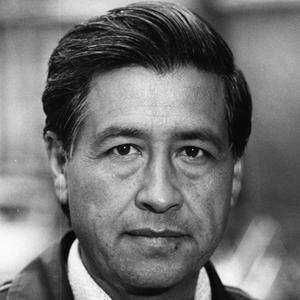

About three months after Cesar Chavez died in April 1993, The Nation magazine published an essay by Frank Bardacke on the famed farmworker union leader-organizer. Entitled “Cesar’s Ghost: Decline and Fall of the UFW,” the article asserted that the United Farm Workers was no longer primarily a farm worker organization, but instead a “fundraising operation, run out of a deserted tuberculosis sanitarium,” and “staffed by members of Cesar’s extended family.”

Bardacke, a former farm worker and UFW member who later became an adult education teacher in Watsonville, California, offered a hard-hitting analysis of the union’s precipitous demise. While he emphasized that it was ultimately due to “the overwhelming social, financial and political power” of agribusiness in California, he insisted that the UFW’s “internal errors” played a significant role. Indeed, Bardacke contended, by the 1970s when the storied union was at its highest point, some in California agribusiness had concluded that they would have to learn to co-exist with it. “Why wasn’t the union,” he then asked, “with perhaps 50,000 workers under contract and hundreds of militant activists among them…able to seize this historic opportunity?”

The answer he offered emphasized how the union’s historic effort to force the hand of California’s major growers via a national boycott of table grapes—what he called the “boycott tail”—had come to “wag the farmworker dog.” This tactic had the effect of diverting the best farmworker activists away from organizing in the fields and into the boycott offices in major cities, thus undermining the union’s power in the workplace. Bardacke situates this strategic reallocation of resources as one among many poor decisions and campaign-related mistakes the UFW committed, calling it “one of the least democratic unions in the country.” This oversight denied the rank and file members—other than those loyal to the status quo—the effective avenues to make themselves heard, and to effect change. Hence, the UFW was weakened, and when the growers and their allies counter-attacked, vulnerable.

The magazine received “a great deal of mail” in response to the piece, the editors reported in November 1993—some of it supportive of Bardacke’s analysis, but much of it quite angry. In one published letter, the late poet Adrienne Rich characterized Bardacke as a “disenchanted white man” and the article’s tone as “mean-spirited and cynical.”

“I don’t get it,” Bardacke replied. “What is cynical about believing that an open discussion of U.F.W. history might help to rebuild the farmworker movement?”

The article and the exchange of letters answered a lot of questions I personally had at the time, while forcing me to confront lingering illusions I had about Chavez and the UFW. Before moving to the Golden State three years earlier, I knew little about Cesar Chavez or the union, other than the largely hagiographic legends associated with both: a selfless man of humble origins, committed to nonviolence, who founded and led a movement that dramatically changed the living conditions of marginalized farmworkers in the Southwest—particularly in California. I envisioned a large, dynamic, and highly visible worker-led organization. But what struck me in my first few years in and around Los Angeles was the near absence of the UFW in the state’s political scene, and the critical rumblings about the union I heard from many of those I encountered who had been associated or allied with la Causa.

I learned not too long after the article’s publication that Frank Bardacke was working on a book about Chavez and the UFW. It was a book I eagerly awaited, and one for which I would I have to wait a very long time.

It turns out that the approximately 18-year wait was more than worth it. The result of Bardacke’s effort is a truly monumental book: a story of a movement brought to life compellingly, with fluid prose and a captivating narrative, peopled by complex human beings, and insightful, multifaceted analysis. The text alone is almost 750 pages. Given the length, along with the intricacies of the story Bardacke so deftly tells, it takes a while to wade through the book (one that was twice the length, Bardacke reports, before his friend and editor Joann Wypijewski cut it down to a more digestible size). Still, it is such a rich and engrossing story, it left me wishing it were longer. It is one of those very rare, great works of social history—I think here of Charles Payne’s I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle as a comparable tome—that a reader encounters in a lifetime.

Much more than the story of the emergence and evolution of Cesar Chavez as the leader of the United Farm Workers, Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers (New York: Verso, 2011) provides a strong account of the farmworkers that were the ultimate source of the union’s dynamic strength, and their struggles in alliance with and against Chavez. In the book’s opening, Bardacke introduces the reader to one of those workers, Pablo Camacho, an individual who was part of the UFW’s backbone when the union was at its height and with whom the author had worked in the field during the 1970s. When Bardacke encounters him years later in 1994, Camacho, at 61 years of age, is still working in the fields packing celery, but without the benefit of a union contract. He characterizes the UFW as “the best thing that ever happened to California farm workers.” It is an assessment with which Bardacke concurs.

That it was “the best thing” makes the union’s demise all the more tragic. And, truly, in many ways, the book reads like a Greek tragedy as it tells a story in which an exceptionally gifted, yet tragically flawed individual looms large, one whose hubris helps to destroy what his great dedication and talent—on which Bardacke sheds ample light—have played a leading role in building.

While many writers have recounted the story of Chavez and the UFW, what makes Bardacke’s book stand out is its breadth and depth, and the wealth of complexity of his analysis. Moreover, it provides a highly unique contextual framing for understanding how and why Chavez and the union made the choices they did. Bardacke’s writing thus includes discussions of the specifics of farm labor in relation to different crops, ideological influences on Chavez, and various political-economic developments particular to the time of the UFW’s rise. It also invaluably brings to light how the shift in the composition of the union’s membership over time—from mostly native-born (mostly Chicano/a) to largely transnational Mexican (and thus non-U.S. citizen)—related to debilitating conflicts within the union.

In addressing these matters, Bardacke stresses the need to avoid reducing the union’s rise and fall to one person, a small number of individuals, or the internal workings of the UFW. He insists that to comprehend what took place requires an understanding of the very nature of agribusiness—which, he explains, is not a single industry, but “a series of separate but related businesses that specialize in different products”—and of work in the fields, which involves piece-rate crews he likens to athletic teams given their physical skill and stamina and their internal solidarity. An adequate understanding also requires, he argues, a deep appreciation for “the political weight of the union’s friends and supporters measured against the weight of its enemies, and how that relationship changed over time.”

What facilitated the rise of the UFW was a deep history of struggle on the part of California farmworkers. While images of grim-faced migrants stoically enduring their plight dominate the national imaginary of life in the fields in the 1930s, for example, largely left out of the photographic record are “farmworkers throwing back tear gas canisters, or angrily confronting scabs, or giving a rousing speech at a mass meeting.” Such events “happened on a regular basis,” states Bardacke.

It was a history in which braceros—contract laborers brought to the United States from Mexico between 1942 and 1964 via a series of accords between the governments of the two countries—played a role. While braceros were slow to exercise their collective power—like other immigrant labor groups, Bardacke insists—this began to change in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Growers supported the Bracero Program from its inception as a way of increasing their control over the labor force and as a way of quelling rebellion among local workers. Increasing bracero participation in the revolt in the fields, however, led the growers to reconsider the program’s wisdom, contributing to its ultimate demise.

The legacy of struggle, combined with the highly exploitative conditions in the fields, made for fertile organizing soil—as did the Jim Crow-like conditions that many of Mexican origin experienced in California during this time. (Gilbert Padilla, who helped Chavez to found the UFW, recounts with bitterness his childhood growing up during the 1930s in Azusa, a city in Los Angeles County, where the public pool was only open to Mexicans and African-Americans on Fridays. On Friday nights, the city would drain and refill it so that whites could swim in water free from alleged contamination.)

Cesar Chavez was the gardener/organizer who helped that soil bloom. Born in 1927 outside of Yuma, Arizona, he saw his father lose almost all his assets, and, ultimately, the family ranch during the Depression. An Anglo landowner who lived next door paid the remaining portion of Librado Chavez’s overdue tax bill and seized his land. The Chavez family took to the road and became migrant farm workers in California, experiencing firsthand its structural injustices and daily indignities.

An alliance with a Catholic priest when Cesar was in his mid-20s exposed the future union leader to the ties between the Church’s religious doctrine and its teachings on social justice, ones assuming and accepting hierarchy within both the Church and society. It was through this alliance that Chavez soon began working with the Community Service Organization (CSO), an entity founded by the renowned organizer and writer Saul Alinsky, a man who had a deep impact on Chavez’s thinking. Initially working on voter registration, Chavez remained with the CSO as an organizer for ten years.

Bardacke’s fascinating chapter on Alinsky and how it informed Chavez’s mode of organizing alone is more than worth the price of the book. Despite the title of his 1946 best-selling Reveille for Radicals, Alinsky, Bardacke shows, was hardly a leftist; he was anti-communist, and Alinskyism “positioned itself as an alternative to New Left politics.” Key among Alinsky’s basic assumptions were the notion that self-interest—not ideology or ethics—is what motivates people; that the hero of social movements is the organizer, one he defined as someone who does not have pre-conceived ideas of what people should do, but instead follows the democratic lead of the community in determining what problems are in need of redress, serving as a gentle guide and facilitator; and that organizers should come from outside of the communities in which they work, as insiders tend to be blinded by their own petty ambitions and alliances.

While Alinkyism appears to many as a non-ideological mode of organizing, Bardacke insists that such a view “misses the point.” Alinskyism, he says, “meets the first requirement of a political ideology: it provides a guide to action.” More importantly, its veneer of non-ideology masks how “so many of its ideas are taken straight from the almost invisible ideology that we live and breathe: the ideology of American democracy.” As such, Alinskyism offers no structural critique of the U.S. political-economy and the associated institutions; indeed, it sees them as fine. For Alinsky, the problems associated with what he calls “democracy” in the United States result from a lack of participation: it is we, the people, and our decisions to act (or not) that are the source of the problem—and the solution—not the highly circumscribed arena in which what passes for “politics” takes place. Such were the ideological and practical shortcomings to which Chavez more or less confined his efforts.

Through his work with the CSO, Chavez found himself frequently on the supportive fringes of farmworker struggles, not least in California’s Imperial Valley. In 1960-61, while Chavez served as the executive director of the CSO in the valley, the region saw a wave of strikes—ones that eventually saw braceros unite with local farmworkers as they rebelled against the growers. In early 1962, Chavez tried to convince the CSO’s annual convention to dedicate resources to farmworker organizing. When the delegates refused, Chavez left the organization and daringly set out to build what would soon become the National Farm Workers Association (NWFA), focusing his efforts in the Central Valley. (The NFWA merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, made up largely of Filipino workers, in August 1966, and became the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, or UFWOC.)

Critical as he was, as a good Alinskyite, of what he saw as the overly bureaucratic nature of unions and their confrontational style, Chavez resisted the notion that the NFWA was a union for a long time. Instead, he asserted that the NFWA was an “association” as a way of remaining loyal to the union’s social movement pretensions, and Chavez’s own emphasis on the self-help and mutual aid traditions of the community-based organizations created by Mexican immigrants beginning in the late 19th century. But when the NFWA signed its first contract in April 1966—with a table grape grower—it effectively became a union. By that time, Chavez, despite his many misgivings, had already decided that the NFWA should affiliate with the AFL-CIO. It wouldn’t be until 1972, however, that the marriage would take place and the union would become the United Farm Workers.

While many growers painted Chavez as a wild radical, his politics tended to reflect the establishment liberalism of the time. He embraced “social unionism”—the notion that unions should be about more than the immediate bread-and-butter interests of their members and aim for broader reforms within the political parameters of the possible. This allegiance alone was sufficiently progressive to attract broad support from both liberals and radicals. Chicano students, for example, strongly supported the UFW and Chavez—this despite the fact that Chavez was a firm supporter of the Democratic Party, was not a Chicano nationalist, refused to criticize the U.S. war in Vietnam (until 1969 when the Pentagon increased it purchase of boycotted grapes), and championed strong policing of the U.S.-Mexico border—positions fundamentally at odds with most Chicano students.

The 1960s was an auspicious time for the UFW to emerge as the socio-geographical isolation and ethno-racial barriers that had long undermined farm worker organizing were not what they had been in earlier decades. Improvements in communication and transportation technologies—and related infrastructure—“had shrunk the country,” writes Bardacke, “and brought the California fields closer to Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, and New York.” And World War II and the civil rights movement had helped to give rise to interracial solidarity, allowing for the possibility that whites would support Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant workers.

These factors were highly significant in a building a broad coalition in support of the grape boycott launched by Chavez and the union. So, too, was the need among liberals for “a constructive, nonviolent, political alternative” at a time when relations between liberals and radicals had become fractured. Divisions related to the Democratic Party’s refusal to seat the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 convention in Atlantic City, LBJ’s escalation of U.S. terror in Vietnam and an increasingly militant anti-war movement at home, as well as the rise of the black power movement and African-American rioting in U.S. cities “had shattered the alliance between liberals and radicals in the early civil rights movement.” The grape boycott provided the glue for some much-needed patching up.

The boycott also did much to build the UFW. It helped to win support among many across the country. Largely through moral suasion and the resulting economic pressure on growers—and some chingaderas (dirty tricks), too (in 1968, for instance, this included a short-lived campaign of firebombing New York City supermarkets selling boycotted grapes)—the boycott won many union contracts as well. The year 1970 saw all of California’s major grape growers capitulate to the union.

This development was not lost on Chavez, referring as he did that year to boycott organizers (not to those toiling in the fields) as “the heroes of the farmworkers’ struggle for liberty.” Such a characterization was classic Alinskyism in its “celebration of the organizer as the agent of history” and its implicit embracing of the necessity for outsiders to make change. It was also both a product and producer of an organization in which ordinary agricultural workers would ironically play a relatively minor role, and “a harbinger of the ultimate struggle,” within the union. Bardacke calls these internal opposing tugs the union’s “two souls”: one involving the boycott, the other the rank-and-file workers in the fields. Organizationally, the two souls were not at all equal. At the beginning of 1974, Bardacke points out, 449 of the UFW’s 544 full-time volunteers worked on the boycott in urban areas far beyond California’s fields. “The union may have had two souls,” he writes, “but its head, heart, and most of its belly were living in the cities.”

If that struggle did significant damage to the union, so, too, did the divide between native-born and immigrant workers, a divide that the UFW not only confronted, but also helped to produce. It was one taken advantage of by growers who sought to counter the increasing power of the UFW by recruiting “illegal” immigrants and green card holders. But rather than trying to build links of solidarity with these workers, Chavez and the UFW struck a U.S. nationalist, restrictionist pose. During a 1967 strike in the Central Valley, for example, Chavez and the UFW demonstrated outside the office of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in Bakersfield, criticizing the agency for not arresting what they called “illegal aliens” and “green carders” (who were prohibited by an injunction from the U.S. Secretary of Labor from working in struck fields). This soon led to the arrests by the INS of hundreds of undocumented agricultural workers. In 1974-75, the union engaged in what it called the “Campaign Against Illegals.” The campaign’s most infamous component was what the union named, in reference to “wetbacks,” the “wet line”: a vigilante group of a few hundred individuals wearing “UFW Border Patrol” armbands who policed a ten-mile or so stretch of the Arizona-Mexico boundary over a three-month period—with the effective approval of local and federal officials—arresting and often brutalizing those they encountered.

As to why Chavez and the UFW engaged in such activities when so many of those employed in the fields were unauthorized migrants—more than half of California’s farm laborers at the time of the Campaign Against Illegals were undocumented—Bardacke posits three possible answers. First, in reference to the UFW’s tactics in the mid-1960s, he argues that Chavez did not foresee what was just beginning at the time: a large demographic shift from Mexican-Americans to Mexican nationals in California’s fields. Second, he surmises that Chavez was simply reproducing an old strategy—opposing the use of migrant workers to undercut native-born ones—which he had utilized in protesting the Bracero Program beginning in 1959. Third, and this is the answer to which Bardacke seems most partial, Chavez cared first and foremost about the boycott, not about organizing farmworkers—ultimately a lost cause in his mind, but one he needed to justify. The combination of “illegals” and the alleged INS failure to police them and the U.S.-Mexico boundary adequately provided a convenient scapegoat.

There was a larger ideological context, of course, that informed the way in which Chavez and his UFW compañera/os responded to agribusiness’s long-standing exploitation of non-citizen workers as a way of undercutting native-born one. It is a context that had long been part and parcel of Mexican-American politics: that of U.S.-American exclusionism. As historian Kelly Lytle Hernandez presents in her book Migra! A History of the Border Patrol, many leaders of the Mexican-American community in the early decades of the twentieth century endeavored to construct themselves as “white.” This trend dovetailed with the tendency of many in the Mexican-American middle class, as represented by LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens), to advocate limits on migration from Mexico and to champion increased policing of the U.S.-Mexico divide. Working class Mexican-Americans were not immune from this worldview. Foreshadowing the activities of the UFW more than two decades later, members of the National Farm Labor Union patrolled the Southwest’s boundary with Mexico during a 1951-52 strike by cantaloupe workers in the Imperial Valley, repelling an estimated three thousand unauthorized migrants.

The UFW’s anti-immigrant activities drove many out of the coalition that Chavez and the union had so carefully built around the grape boycott. So, too, did Chavez’s ill-founded embrace of the autocratic leader of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos—during a 1977 visit to Manila, he referred to the despot, who gave him an award, as “a wonderful man”—and his refusal to retract his praise of Marcos and the dictator’s imposition of martial law in the face of criticisms from UFW members, staff, and the wider activist community. If the unintended loss of coalition members weren’t enough, the increasingly paranoia-inspired Chavez began actively purging from the union his adversaries—a combination of dissidents, leftists, or simply those who even indirectly called into question the ways Chavez thought things should be done. Significantly enfeebled by the 1980s, the UFW was unable to withstand the decade in which the Republicans took power in Sacramento, Ronald Reagan moved into the White House, and anti-unionism emerged with a vengeance. While the UFW still had union contracts, “it didn’t have a united membership and a movement to protect them,” Bardacke argues. Because Chavez “had smothered the farm worker soul of the union . . . [its] body would wither and die. Only the head would live on.”

That Chavez and the small coterie around him were able to do what they did speaks to the organizational dysfunction that characterized the UFW from almost its inception. Power was highly concentrated around Chavez, a master of detail who demanded full oversight of the organization. Despite the fact that there were hundreds of full-time volunteers at the height of the boycott, Chavez was often the person who recruited them. In terms of paid staff, Chavez often conducted the preliminary interviews. Chavez also micro-managed the organization’s finances, overseeing the payment of rent, heat, and food bills of boycott volunteers.

The union’s very structure produced and exacerbated distrust between staff and workers, and between those laboring in the fields and the UFW’s headquarters in La Paz, California. Grape workers were more heavily represented among staffers than lechugeros (lettuce workers), for example, despite their being far better organized and more active at their worksites. On a similar vein, the staff was heavily Chicano, with little representation of transnational Mexicans who, by the end of the 1970s, made up the bulk of the union’s membership. (Bardacke sees this tension as central to the union’s problems—one he did not appreciate when he wrote The Nation article, he admitted in an interview. Not welcoming “the newcomers,” Bardacke writes, was Chavez’s “greatest historical failing”—that and “his commanding role in the destruction of his own union’s farm worker leadership.”) At the same time, there were no locals in the union, and thus no effective channels for decision-making outside of La Paz. Thus, when the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee became simply the UFW and joined the AFL-CIO in 1972—at the private ceremony for which not a single worker representative was present—it brought no structural changes within the union along with it. For Bardacke, this empty reorientation was a highly ironic situation: “the UFW, supposedly a radical alternative to the old-time AFL-CIO unions, actually had less structural democracy than most of its famously bureaucratic sister affiliates, whose workers could at least vote for their local officials.”

The UFW’s structure augmented the difficulty of challenging Chavez, as did the sense of infallibility that developed around him. As Chavez embarked on high-profile fasts and associated activities, his self-sacrifice made him saint-like in the eyes of many—and maybe in his own. It also perhaps allowed Chavez to do things that, on their face, appeared as antithetical to and undermining of everything for which he stood—from driving dedicated staffers out of the union after issuing wild allegations of betrayal, to supporting Ferdinand Marcos, to embracing a cult-like, intentional community called Synanon, which he destructively involved in the staff’s internal affairs.

Such actions facilitated a widely held belief that what ultimately befell Chavez, and, by extent, the UFW, was that the union’s founder and leader simply went crazy; it was pure delusion, so goes the story, that led him to destroy his creation. This is an account Bardacke rejects, for “[i]f the leader went nuts, nothing else matters—not the lack of locals, nor the antidemocratic ethos, nor the financial, physical, cultural, linguistic, and political separation between the membership and the staff, nor the plain old mistakes.” What makes more sense, Bardacke declares, is that the UFW itself was crazy: it destroyed Chavez, not the other way around.

Apart from a brief epilogue that tells what has happened to the principal actors in Bardacke’s saga, the story ends in 1988. As the growers had thoroughly reorganized California agribusiness so as to undermine the ability of a union, too weakened by internal conflict, to challenge it, the UFW as a union was by then, for all intents and purposes, effectively dead.

Following the death of Cesar Chavez, the UFW, Bardacke reports, “made a genuine effort to return to the fields and regain its identity as a union.” Yet today, the UFW has a little more than 1,000 strawberry workers under contract in California, and somewhere around 5,000 other members working under union contracts “not much different from the current low standards in the California fields.” This startling regression in a state with hundreds of thousands of farmworkers—many of whom live and labor in horrendous conditions, earning wages less than those of 40 years ago and receiving poor protection from authorities.

Such a situation is not unique to California, but speaks to the nature of agribusiness in the United States, and the poverty of legal protections afforded to workers. The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, for instance, excludes agricultural and domestic labor from minimum wage and overtime protections. It also permits the employment of children beginning at the age of 12. As Gabriel Thompson contends in a recent article on the exposure of child workers in tobacco fields to poisons (nicotine and toxins from pesticides), a “grower who hires a 12-year-old to work seventy-hour weeks in the summer is well within the letter of the law.”

Meanwhile, in three states (California, Colorado, and Texas) Cesar Chavez Day is now an official state holiday; nationally, activists are working to make it a federal holiday, for which then-Senator Barack Obama expressed support in 2008. Moreover, Hilda Solis, Obama’s first Secretary of Labor, renamed the Department of Labor’s auditorium after Cesar Chavez in 2010. And, more recently, the U.S. Navy named one of its ships after the union leader, a man who championed non-violence.

Such moves to canonize Chavez do little to help remedy the plight of today’s farmworkers. Instead, they might very well prove counterproductive: they effectively reduce the farmworker struggle to one man, while their hagiographic nature hides the contradictions and shortcomings of both Chavez and the union. At the same time, the white-washed representations they embody serve to mask not only the hard-hitting critique of agribusiness made by Chavez and those with whom he struggled in alliance, but also their drive and determination to bring about just wages and dignified conditions for farmworkers.

The memory alone of that struggle and commitment is perhaps the greatest legacy of Cesar Chavez and the union. Just as it required half a century ago when Chavez and the nascent UFW began organizing farm workers, to realize their goals today will necessitate a union strategy that positions itself as part of a dynamic social movement, and one that functions as a vibrantly democratic entity; it must not only breed strong leadership with strategic thinking, but also allow for dissent, and therefore for new leaders to emerge organically from within. Chavez paid a lot of lip service to the union-movement marriage, but it’s one that he ultimately rejected in practice. True movements, Frank Bardacke asserts, are fundamentally democratic.

Trampling Out the Vintage powerfully demonstrates the great things that everyday people, many of whom Bardacke introduces to the reader, can accomplish in the face of tremendous adversity. But in showing just how difficult it is to challenge deeply embedded political-economic power, the book also illustrates how a movement’s capacity to undermine its grassroots base by restricting the space allowed for democratic practice is a sure way to stifle even the possibility of overcoming that power. At a time when worker organizing in the United States—from Seattle to Chicago to Atlanta—seems to have newly-found militancy and vibrancy, lessons from the shortcomings of Chavez and the UFW are ones we ignore at our collective peril.

Joseph Nevins teaches geography at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Among his books are Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid (City Lights/Open Media, 2008) and Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on “Illegals” and the Remaking of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (Routledge, 2010). For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. Now you can follow it on Twitter @NACLABorderWars.