This past Wednesday, President Barack Obama made a historic announcement about the normalization of relations with Cuba. Although there had been rumors floating around the streets of Havana, most people on both sides of the Florida Straits were taken by surprise at the new policy toward Cuba, which would reestablish diplomatic relations, review Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism, and increase travel and commerce between the countries.

There was jubilation and celebration from many who had long awaited this decision. There was condemnation by hard-liners in the government who saw the decision as a concession to the Castro government. And there was much speculation. Would this mean McDonalds, Walmarts, and unbridled capitalism for Cuba? What would be the fate of American political prisoners like Assata Shakur who are protected by the Cuban government? When would you be able to plan your next vacation to the island?

One of the issues that has been at the heart of these debates has been the use of the Internet by ordinary Cuban citizens. Currently, only those with government jobs enjoy legal access to the Internet. In his announcement, Obama pledged to increase telecommunications connections between the countries, and under the new regulations, American telecom providers are permitted to provide Internet infrastructure and services to Cuba. Alan Gross, a subcontractor for the American agency USAID who was released Wednesday on humanitarian grounds, had been arrested for bringing non-licensed equipment to set up WiFi Internet access on the island. And much has been made of the Cuban blogger Yoani Sanchez who has been celebrated abroad for her clandestine use of social media to portray life in Cuba.

Open access to the Internet is generally equated with freedom. If more USAID contractors like Gross could be bringing the Internet to Cuba, the argument goes, then there would be greater individual freedoms. But do Cubans really want Internet freedoms if they are provided by the United States? Although Obama has pledged offers of Internet technology, Cubans are likely to be suspicious. Given the revelations by whistleblower Edward Snowden about the United States using the Internet to spy on its citizens, it is unlikely that Cubans will feel comfortable entrusting their everyday browsing with an Internet management infrastructure whose history demonstrates a complete disregard for privacy protections.

Others wonder if the Cuban government would allow its citizens to have such free access to information through social media and the web. What may be surprising to learn is that many already do. It’s not just through the informal market in underground Internet connectivity that Cubans are able to access a slow and unreliable Internet. But for the past year, through a phenomenon known as “El Paquete Semanal,” or “The Weekly Package,” Cubans have created an alternative to broadband Internet.

The Package is one tera (or a thousand gigabytes) worth of material that is downloaded weekly by people with access to high-speed Internet. It is not known who they are or where they get this access, but some speculate that it must be under government radar or the whole production would have been shut down. The Package is distributed throughout the island via the informal economy, from the urban enclaves of Havana to the mountains of Guantánamo. The package is an eclectic collection of Hollywood films, Cuban films, Youtube clips, Spanish language news websites, illegal classified listings, computer technology websites, Japanese anime, instructional videos, music videos, and much more. Cubans are able to watch American television series like Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones. The Package also includes advertisements for some of the new local Cuban businesses such as restaurants, English classes, and health spas. Most people don’t get the entire Package, but just request certain categories.

There is an entire new sphere of employment that has resulted from the Package, an informal sector network of neighborhood distributors, armed with large hard drives, who sell parts of the Package for as low as one convertible peso, equal to about one U.S. dollar. No one knows exactly how the Package got started and there are myths that it was one person who now has an entire network of tech workers in charge of preparing one of the sections each week. In an interview with the online magazine, Contemporánea Cuba, one of the workers explains how he puts the music and video section together and the difficulty of getting Cuban material: “I get it here and there, you know, trying to get the greatest possible variety...It's hard, but I do it. So you see that we have videos and music from almost all of Cuba’s leading artists, salsa, electronic music, hip hop...Even Omara Portuondo!”

There is certainly a level of control exercised by those who make the selections. But there is also a strong feedback loop, with a built-in system for users to ask why certain items are not included, and to make requests for others. A local distributor in the suburb of Vedado said that TV series and soap operas are most popular along with music and the illegal classifieds. There are films from small and distant parts of the globe. One cultural critic writes that recently, independent films from the remote Polynesian island of Niue have become popular. People also seem to like the category “Interesting Variety,” which is a collection of all kinds of things from jokes to fashion tips to healthy recipes.

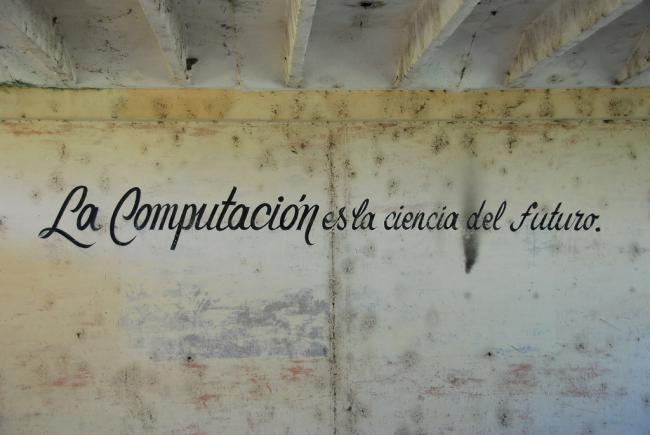

For all the talk about bringing Internet freedoms to Cuba, could it be that Cubans have themselves created an alternative to the corporate-driven World Wide Web by coming up with their own alternative networks for consuming and sharing information? In contrast to recent depictions of Cuba as a technological backwater, frozen in time, deprivation has yet again spurred Cubans to new creative heights. When considering the enormous opportunities that will be created by Obama’s announcement of historic policies, it will be important to keep in mind what Cubans want and need—and not what we think they do.

Sujatha Fernandes teaches Sociology at Queens College and the Graduate Center, CUNY. She is the author of several books including Cuba Represent! Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures (Duke University Press, 2006), and, most recently, Close to the Edge: In Search of the Global Hip Hop Generation (Verso, 2011).

Alexandra Halkin is a documentary filmmaker and the Director of Americas Media Initiative (americasmediainitiative.org), a non-profit organization that works with Cuban filmmakers living in Cuba. She is also a Guggenheim and Fulbright fellow and the producer of a number of award winning short documentaries made in Mexico.