This article is a joint publication of NACLA and edmorales.net.

The mass media of news and entertainment is ideally a reflecting pool where society can revel in its own image, but Latinos in the United States have to look long and hard to see themselves, and when they do, it’s a distorted picture. The lack of consistent and accurate portrayals of Latinos and their lives on network news, television shows and Hollywood films has been examined many times in the last 20 years, but the release of “The Latino Gap,” a new study by Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, should prove to be a landmark occasion.

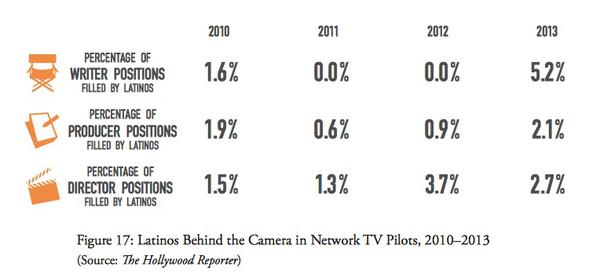

While most studies like this present statistical analysis of the paucity of Latinos as the subjects of news stories, in front of and behind the cameras, “The Latino Gap” also includes important critiques of the diversity-building efforts by networks, studios, and media conglomerates, stresses the importance of social-media driven advocacy efforts to block negative representations of Latinos, and makes specific recommendations to address several problems.

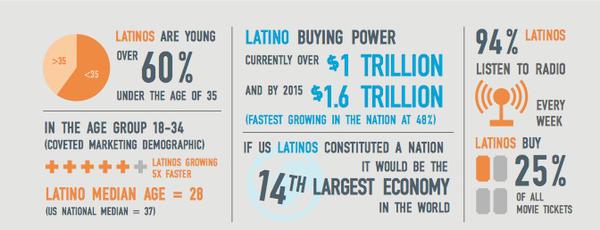

Armed with the usual array of Latino boom statistics, the report makes the case that, despite the fact the Latinos are a continually growing demographic presence, mainstream media does a surprisingly poor job in representing us, and is at the very least sluggish in addressing the issue. While there are political realities tied to the presence of Latinos in the media, in front or behind the cameras, doing the reporting or assigning the stories, it's almost shocking that an economic system based on accumulation of mass profit would be so inept in reaching a rapidly expanding consumer pool. This resistance, according to the report, seems to be significantly driven by both corporate cluelessness and anxiety over racial and cultural difference.

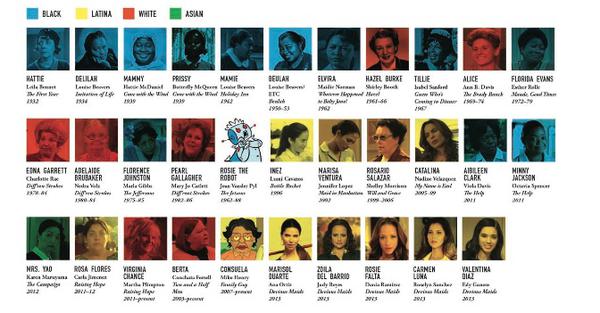

Among the findings are the continued disproportionate presence of Latino presence in entertainment on and off camera; changes in acting personnel moving away from leading men and towards women; an analysis of stereotypes and their harmful effects, the sorry state of news reporting about Latino issues; the interactive effects of Latino content and viewership; the power of consumer pressure on networks; and they way Latinos are surging in internet usage as content providers and consumers, in some ways driving the information age. The focus on the last two areas imbues the report with a sense of optimism that turns a cogent exercise of statistical analysis into a kind of uplifting manifesto for future advocacy.

This week I interviewed Frances Negrón Muntaner (director of the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, where I am a faculty member), who authored the report with the help of Chelsea Abbas, Luis Figueroa, and Samuel Robson. What follows is our exchange, which I hope can shed even greater light on the many issues she and her co-authors raise in this ambitiously thorough and thought-provoking report. (The complete version can be accessed here.)

Ed Morales: It was impressive that you included suggestions on how to combat the myriad problems you lay out. How much movement have you seen in recent years to seriously deal with these issues?

Frances Negrón Muntaner: Many people, inside and outside of the media industries, are trying to move the needle every day. They meet with decision-makers, organize campaigns, develop professionals, comment on existing media online and in print, pitch new projects, and conduct research. Overall, there is more awareness, level of organization, and insistence on the matter now than in prior decades. But there are some challenges. One is that media marginalization is not only a Latino issue yet coalition building is difficult for a number of reasons, including that the gains of one group are often seen as a threat to another. Two is that there are more media choices today and this means that people can be living in very different media realities yet continue to be affected by what they literally don’t see. So, the present moment has great potential but there is a need to create more effective mechanisms for people to connect the dots and work together.

EM: Your findings seem to indicate that news media representations of Latinos may actually drive, or greatly affect movie and TV representations of us. Would substantial change in the way the news media covers Latinos affect Hollywood portrayals?

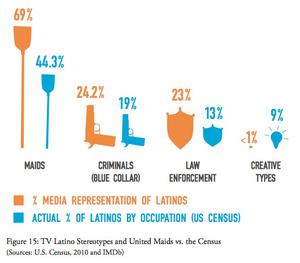

FNM: If I had to pick three advocacy priorities, news would be one of them. This is the case for various reasons. Although entertainment shapes much of how and what people feel about the world, news still serves as a benchmark for what most consider “real” and objective. It has a certain authority. That in news Latino inclusion is extremely low and stereotypes remarkably prevalent, and that both frames (news and entertainment) largely reaffirm each other, then has important consequences. For instance, when viewers see a white criminal in a movie or show (and they see plenty), it’s generally perceived as a character, not a reflection of whites as a group. But when audiences see Latinos as criminals, the characters are a confirmation of an intrinsic quality of the group as a whole whether they appear in a movie or in the news. In this regard, my sense is that until we have various different frameworks to think about who Latinos are, change across all mainstream media will continue to be slow.

EM: Do you find that stereotypes not only damage Latinos standing in society but also have the effect of reinforcing those roles in communities? Such as, even if a young Latino dodges a life of crime usually prompted by socioeconomic circumstances, they make disproportionate choices to pursue careers in law enforcement, rather than choosing a career in medicine, or being a creative type or academic?

FNM: Stereotypes affect everyone. A subordinated group becomes culturally visible and recognizable to itself and others through a specific repertoire of stereotypes. As cultural theorist Stuart Hall argued, identities are not made outside of representation but through it. So, stereotypes make the group distinct; they are both an idiom through which the group is perceived and a way through which the stereotyped seeks to understand his or her place in society. In other words, stereotypes contain and channel our imagination and it takes an effort to see otherwise. This is why new and unexpected narratives are so important. They start us in a new direction by suggesting that there are more worlds of possibility available.

EM: Do you think it’s significant, in terms of how Latinos are represented through gender, that the Latin Lover has vanished and more women are prominent in film and television?

FNM: I do. I am currently writing an essay about the rise of Latina actresses as Hollywood producers and I have two working hypotheses. One is that a number of Latina actresses, particularly in the last decade, began to take action regarding how limited their possibilities were under the current system by using their star currency to gain access to behind-the-camera power. The contradiction here is that these actresses mostly produced their capital by playing stereotypical beauties and still need that capital to have public influence. The classic here may be the much-repeated assertion that “it took a beautiful woman (Salma Hayek) to make Ugly Betty.” The second hypothesis is that once Latinos exceeded 10% of the population, Latino men no longer appeared as harmlessly alluring or exotic but real competition to dominant masculinity. The result is that Latino men play supporting roles, characters that don’t compete for resources with the protagonist; or perform roles as disposable threats that are eliminated in part to prove the superiority of the (generally) white protagonist. Because, ultimately, who wants to compete with the sexiest men alive? Better to just get rid of that idea.

EM: Does Latino participation in alternative media such as video-posting, blogs, Twitter, and Instagram represent something that would logically occur in most groups under-represented in the mainstream media? Do niche medias like that go a long way in representing a more accurate portrayal of Latinos and possibly preferable to mainstream media representation?

FNM: There is still work to be done in order to conclude whether going online is a clear trend for all underrepresented groups, but it is a good hypothesis. A well-researched example is that of Asian Americans. Similar to Latinos, Asian Americans are severely underrepresented in mainstream media outside of certain action genres. Yet, they are proportionally very active on the Internet as content creators and talent. So, we can definitely say that some groups that are ignored or marginalized by mainstream media and have become avid digital technology adopters, are using these tools to create different mediascapes. A great value of this media is that it allows us to represent ourselves how we think we are, imagine or aspire to be; rather than as we are supposed to be.

EM: Do Latinos who do not emphasize their identity have any impact for Latinos in the United States? I'm referring to the comedian Louis C.K., or various "Latino stars you didn’t know were Latinos" in TV like Frankie Muñiz? Is it significant that the Afro-Latino actors mentioned rarely if ever play Latino roles?

FNM: I think Latino performers who do not emphasize Latino identity or highlight only parts of their identity do have an impact as well. Viewers often know that these actors are Latinos. This could lead some to assume that this is one way to go, and it has a long tradition in entertainment. Many of the Latino stars that people celebrate today hid their Latino identities. Still, it can also stimulate others to question why is this the case, raising broader questions about power. In addition, and yet another way to think about this question, is that freedom is the power to be and not to be. Everyone should have the freedom to imagine themselves in different ways. In this sense, to me the problem is not so much that, say, Afro-Latino actors are not always playing Afro-Latino roles. But that there are so few opportunities to play Afro-Latino characters and tell Afro-Latino stories because these possibilities are not valued by media decision-makers.

EM: Along those lines, how do we measure the quality rather than the quantity of representation? For instance, two ‘70s shows you mention, Chico and the Man and Fantasy Island had wildly different meanings for Latinos. The former was a breakthrough for a Puerto Rican star comedian (Freddie Prinze) and the latter was a non-Latino-specific role played by Ricardo Montalbán, a leftover from the Good Neighbor Policy films, a faded “Latin Lover.”

FNM: It’s a challenge. One thing that I am interested in doing is to create a complex map where we link and analyze how the media landscape looks and changes in relation to broader economic, social, and cultural contexts. For instance, what is the impact and long term influence of a character or show? Two, how do different audiences position themselves in relation to specific characters and stories? For instance, some people argue that (I Love Lucy’s) Ricky Ricardo and (Modern Family’s) Gloria Delgado are basically the same character. But if they are performing in different contexts, and we know that repetition changes cultural meanings, how do we grasp the difference? Another challenge is that viewers literally don’t see the same things. Freddie Prinze is a good example. As we note it in the advocacy section, one of the campaigns in the 70s was to “end the Latino subservient stereotype in Chico and the Man.” So, while some saw the show as a breakthrough, others saw it as more of the same.

EM: Should U.S.-Latino activists call on privileged Latin American and Spanish stars to lend solidarity to efforts to increase Latino representation in mainstream film and television? How much responsibility should they have in this effort?

FNM: Successful movements and campaigns require the support of many at all levels of the power and prestige structure. In this way, I do think there is room for more dialogue and collaboration among U.S. Latinos and Latin Americans in the media industry. Among other things, working together may contribute to disrupting the perception that U.S. Latinos are inherently less talented or not working hard enough. I have heard young U.S.-Latino actors say that the proof that Latinos are to blame for their limited access is that Mexicans and other Latin Americans do so well in Hollywood. The latter are seen as inherently more sophisticated and universal rather than differently, and at times more advantageously, positioned in the global cultural economy.

EM: Does diversity really pay off if it involves the reinforcement of stereotypes, as referred to in the Devious Maids example said to increase Latino viewership of the Lifetime Channel?

FNM: This is another instance of why evaluating quality is complex. Devious Maids has a fairly high rate of Latino, mostly Latina, viewership. And while we could say that the actresses are playing a stereotype, the maids here are the protagonists and they are often the most compelling characters. One could then argue that the show is using a stereotype and challenging it at the same time, although the jury may still be out on its effects. The other major question is whether it is more politically productive to see stereotypes than to see nothing at all. Most media scholarship would suggest that the stereotype, despite its potential toxicity and limitations, allows for other possibilities to emerge through parody, disruption, and inversion. Also, by visualizing what may be hard to articulate, the recognition of stereotypes may allow people to challenge and organize against dominant structures and ways of seeing. On the ground, those Latino actors and creative talent involved in shows that one may view as stereotypical may similarly use the experience to open up new opportunities. In sum, it’s complicated.

EM: The report’s critique of diversity efforts in Hollywood as ineffective is really strong. It seems to be reflective of a major problem at all levels of professional work, but particularly in creative fields. The Girls controversy was a glaring example of how the mindset of prominent media creators is often out of touch. Should Latinos, who consume so much media, begin boycotting mainstream media through the social media activism you describe not just over extreme stereotypes like the Lou Dobbs show, but for systematic change?

FNM: Media users and consumers, including Latinos, have a lot more power than they think. If consumers leveraged more of that power on a daily basis by weighing more forcefully on what is available, we could collectively have more influence regarding what we see and how we see it. If users produce more of their own media, effectively blurring the distinction between consumer (assumed to be passive) and producer (assumed to be active), and actualize what is not present in the so-called mainstream, we can also contribute to a narrative shift and the creation of new paradigms of production and distribution. In this regard, it seems to me that challenging the media today requires multiple practices: daily refusals, creativity, campaigns against toxic movies and shows, and long term organizing to democratize media structures. The importance of this engagement is also not short-term. We are in a moment of great media change and there is no reason to believe that the promise of an open Internet will be resolved in the user’s favor. This outcome will heavily depend on how engaged and organized people are around questions of access, technological development, and ownership, among others. In my view, it’s definitely a good moment to call for “action!”

Ed Morales is a freelance journalist and author of Living in Spanglish (St. Martin’s Press). He teaches at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race. All graphics by Stephen Chou.