This article is a joint-publication of NACLA and edmorales.net.

Si te quieres divertir

Con encanto y con primor

Solo tienes que vivir

Un verano en nueva york

- El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico

Every year for 15 years now, New York has hosted the Latin Alternative Music Conference, a four-day affair that tries to make a case for emerging Latin music that diverges from traditional genres like salsa, cumbia, norteño, tango, bomba, plena, son cubano, milonga, bachata, merengue, etc. Characterized at first by rock bands that fused nationalist codes with an emerging global youth culture, Latin alternative has since embraced hip hop, funk, electronica, global bass, reggaetón, and reggae, among other genres, and has become a mixing space for border-thinking millennials. While there is an understandable degree of skepticism from monolingual Americans who don’t grasp the subtle Spanglish spin placed on established youth culture genres as well as Latinos who don’t want their funky realness corrupted by MTV-ish dillettantery, there is a power in Latin alternative’s attempt to create different identities, making the case that the best thing to do is get involved in the defining process.

The odd thing about the LAMC is that it imports an essentially West Coast-driven operation—namely founder Tomás Cookman’s Cookman International and Nacional Records, which distributes many of the biggest Latin alternative acts—into a New York milieu where what most people think of as “Latin” music, itself a fusion of Latin American genres with New York attitude, has held sway since the 1930s. Rather than create Latin alternative music, since the 1970s golden age of salsa New York Latinos have strived to make their marks on genres like jazz, rock, and hip hop by fitting in with the dominant model and expressing themselves mostly in English. Marc Anthony and Jennifer Lopez, once Latin music’s reigning power couple, are good examples of the New York Latino idea of mastering the prevailing genres of salsa, Latin pop, and r&b dance music.

But since the early years of the LAMC, New York’s Latino zeitgeist has changed substantially, and globalization, gentrification, and plain old proliferation of new immigrant groups—as well as the marginal millennial people of color scenes in various sectors of Brooklyn and other outer boroughs—have created an alternative to Latin alternative. This year’s edition of LAMC painted a picture of both the established norms of Latin alternative while still managing to represent its changing face. And at the same time, all around town, there was a lot of alternative-to-alternative stuff popping. In the chaotic context of the current crisis of kids at the border and the so-called Americans who hate them, it’s evident that the old cultural order is rapidly falling apart.

The night before the LAMC kicked off, Los Rakas appeared at one of those auxiliary spaces at Webster Hall, rocking their Panabayan (they are originally from Panamá but now live in Oakland by-the-bay) reggae-rock to a crowd that also believed they were “raka.” The loving epithet is a statement more or less implying unity among Afro-Latinos, who often are doubted as authentic by both African Americans and Latinos. Their almost-new album on Machete Records, El Negrito Dun Dun and Ricardo, is often compared to the Outkast’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below double CD set, but there’s nothing derivative about it. Expanding on their established hip hop-reggae groove, the duo explore subtle post-disco r&b territory where no Latin alternative band has gone before.

Natalia Linares, formerly of Cookman International but currently a fearless curator of underground New York Latino music that mere mortals can barely keep up with, is part of Los Rakas’s bicoastal management team. Out of a burning need to define new space, she has created a Twitter hashtag called #NowNotAlternative to engage people in a dialogue that wants to redefine alternative. “I want to be respectful of what’s been built but basically say we are new and now and don’t need empire$ to get there,” she texted me. “I’m about bridging people to new Diasporadical sounds of our generation.”

One of the standard bearers of the Diasporadical is Ana Tijoux, who was looking very relaxed in an orange dress and jean jacket performing Wednesday at the opening LAMC jam at Central Park with a full-on rock band of guitar, bass, and drums. She seemed to be a little more influenced by the blues this time out, searching out scats, cutting her rhymes in her coy and angular manner. Much to my delight she picks “A Veces” out from first album, just like she did a few years ago, a soul-searching tune that samples Ahmad Jamal’s “Ghetto Child” (just like Common and John Legend did in 2005). Tijoux, who is Chilean by way of Paris, had an easy groove with the audience, dedicating the more recent “Mi Verdad” to el pueblo Argentino, which was on its way to the World Cup final against Germany. The solidarity with Argentina utterance was a running theme among several performers, who chose a longed-for connection against First World hegemony, refusing to devolve into the angst-ridden nationalist rivalries that often divide Latin America. But suddenly, without warning, the heavens opened up and this year’s LAMC had its first crisis of the tropical. Later in the week she threw down with conventional rock lineup in a club in Greenpoint, and got more specific about her politics on this spot on Democracy Now, where her allusions to Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine, the writings of Eduardo Galeano and her take on the Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership on her latest album Vengo get teased out a little.

The LAMC gets glitzy when you hang out in the Affinity Hotel where the panels, exhibitors and press rooms are splayed out, vying with the lingering vibe created at the shows the night before. “Nuestras Quinceañeras: A Coming of Age For Latin Alternative and the Overall Music Industry” was a Q&A/panel about celebrating the conference’s history and future hosted by NPR locutores Felix Contreras and Jasmine Garsd. There was some talk about the genesis of the “concept,” and glib reminiscences about the emergence of Cookman International, and some further “I was there” commentary by Latin Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences president Gabriel Abaroa.

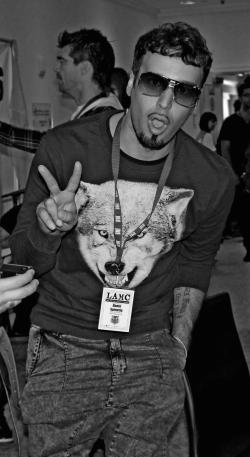

The conference corridors were teeming with seekers of alternative knowledge, but for me it had a kind of high school reunion ambience. Here was José Luis Pardo (a/k/a Afro Cheo), guitarist of Los Amigos Invisibles, there was Enrique Blanc and María Madrigal of La Banda Elástica magazine, and Yuzzy Acosta, original RNE (rock en español) curator, who gave me my first Aterciopelados record. But Dante Spinetta, one half of Argentina’s Ilya Kuryaki & the Valderramas, unfazed in his sunglasses, immediately drew my attention. I remembered meeting him and his musical partner Emmanuel Horvilleur in ’98 in Buenos Aires, so excited after flying to record Leche at Bootsy Collins’s studio in Dayton, Ohio.

Ilya Kuryaki have always been kind of a cult band outside of Buenos Aires—most Argentine rock fans prefer the prog, the synth sound, or even reggae or ska to their demented blend of Chocolate City post-disco soul. That night at Prospect Park, IKV barreled through their most recent effort, Chances, filled with bouncy, competent funk party hooks. Somehow it seemed strange that their biggest score was getting promoted by Oprah Winfrey, who recognized the ‘80s shtick on the single “Ula Ula” a Target commercial. I wanted to ask Dante about the recent Argentina/Wall Street debt vulture trial but had to settle for another rambling version of their dance-funk classic “Coolo,” which reverberated into the gentle slopes of Prospect Park like a Kansas twister.

While a Times piece by the always perceptive Jon Pareles kind of beat me to the punch, the way women have been taking the reins of Latin Alternative has become more obvious as the years pass. This year, two Cuban singers, Diana Fuentes and Danay Suárez, were particularly interesting because they were both seeking a radical new direction while clearly influenced by the Cuban tradition, expressing themselves in distinctly different ways. Fuentes sees herself as a kind of intelligent pop singer influenced by the “feeling” and not the “filin” of the legendary Elena Burke, and has an extraordinary power and range. She’d already been a backup singer for post-nueva cancionero Carlos Varela, a collaborator with the legendary Sintesis, and has recently married Eduardo Cabra, musical director of Puerto Rico’s Calle 13, who produced her soon to be released debut album.

“I’m an alternative pop artist—not really pop, not really alternative,” she said at the conference pressroom. “I’m kind of in-between the two.” Fuentes is splitting her time between Cuba and Puerto Rico, where she has rubbed elbows with the triple-threat artistic genius Rita Indiana, and is excited about the statement her generation of Cubans, with more freedom to travel, are making. “The government really is opening up a lot of doors and I think it’s being reflected in the music,” she said. “This is part of the effort of Cuban youth to transcend the border regardless of the embargo and politics. It’s going to be 55 years of that politics and we haven’t accomplished anything. So now that is becoming more normal to travel, we appreciate this.”

At her live show, Fuentes displayed a remarkably powerful voice and a fluid understanding of various genres, which will be on display when her Sony album Planeta Planetario drops on August 12. At SOB’s acoustic showcase she dedicated a song called “Otra Realidad” to the memory of a July 1994 incident when the Cuban government intercepted an improvised craft carrying refugees out of Havana and many of them died. It’s a symbol those harshly critical of the regime have long seized on, but for Suárez, it’s just about remembering, and offering more evidence of a different kind of politics about the embargo that values change rather than pointing fingers.

“When I signed with Sony Records they told me they hadn’t had a Cubana under contract since Celia Cruz,” smiled Fuentes. “It was amazing news, and I was honored. After so much time, this was finally happening.”

The panel called “Every Centavo Counts: Making Sense of Streaming and the New Digital Economy” was a challenging exercise in discovering how music is being monetized through digital technology. SoundExchange’s Barry Levine set the tone by summing up what has become increasingly clear: “The trend is toward the access model rather than the ownership model.” While it’s certainly that apps like Pandora, and the cognoscenti favorite, Spotify, make more sense to people who don’t want to invest energy in building a collection of music, I get the uneasy feeling something is lost, and we’re inviting all these filters, profiles, and recommendations into our relationship with listening to music. It’s also unclear who wins in this model, where it seems the massive sellers make out better because of the low rates paid by services like Spotify and Pandora to musicians.

Chris Harrison of Pandora tried to explain when a questioner from the audience complained. “How many times would you need to be played on Z100 to reach a million listeners? About 16. A million spins on Pandora is like being played on Z100 16 times. The digital world is changing really fast but now matter how you slice the pie we’re paying more than other services,” he implored. High-profile artists like Thom Yorke have been outspoken about how new artists get screwed by this system, and more than a few eyes in the audience rolled with Rich Bengloff began his response about the difference between songwriters and song producers with “You’re going to hate me for saying this, but…”

Danay Suárez was the revelation of the conference—reports were that her set at Mercury Lounge was stunning, and it seemed her appearance at the acoustic showcase at SOB’s was even more revealing. Just before she took the stage I asked her how she was feeling and she said, “You know, in this other world, where I usually am.” As she slid in next to him, the guitarist began the process, and she began her improvisational journey, bringing the melodic space of jazz into hip hop. Her lyrics seemed to expand on something she had tattooed on her wrist and forearm: “Amor eterno pero solo en una de mis vidas. Voy a morir amándote, un amor una vida.” She’s playful and scatting here, syllables flowing like the ocean, like listening to the tides one night at the cañonazo in the port of Havana. She intones like a profeta on a street corner opening her heart about la vida cotidiana. The crowd reacts to the ebb and flow of her intonations and range. “El amor no va a estar cuando el respeto no alcance,” she croons.

Earlier I’d asked Danay about her response song to Jay Z and Beyoncé’s visit to Cuba and she told it wasn’t really a response, it was the media’s idea, and that it was just a chance to opinionate on the tricky distance between La habana y lo externo. “Politics is complicated because people dare to speak without a political foundation. It’s one thing to say you’re a political leader. My politics is spiritual. Their visit was a direct way to get me to write a song.”

I’d noticed the alternate colors of her beaded wrist bracelet and asked her if she were Yemayá, the Yoruba goddess of the ocean and she laughed, almost scoffed at my suggestion. “These are just colors, a woman gave me this in Oakland. I’m not Yemayá but I have a big connection with water, I like water. But if were going to be an element I’d be the air, so that you could feel me but you can’t touch me.” Yet, there she was, embracing the audience. With an up-tempo riffing from the acoustic guitar, she lets out a squeal of oooooh ay ay ay ay ay, and the crowd engages in call and response.

“I like political themes, I love to read and understand histories,” she said with an air of confession. “But it’s so manipulated. I don’t know how to believe in struggles that I wasn’t a part of. That’s why my politics is spiritual, because it responds to things inside me.”

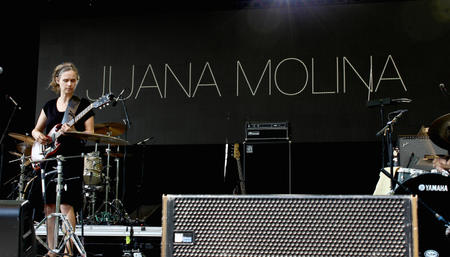

On Saturday afternoon, a modest throng came to Summerstage, and La Santa Cecilia and Juana Molina were dominant. Gotta say Marisol Hernández’s cautionary rant about the distance we create between ourselves by favoring texting and tweeting over face-to-face interacting was spot on. The new generation of post-Chicanos who embrace East LA kitsch, politically aware lyrics and son jarrocho was in the house. Something homey and irresistible about it. Just two days ago, Hernández had made an appearance with J Lo and Michelle Obama at the LULAC convention that happened to be going on in New York at the time. Here in Central Park, just a hundred yards or so away from the Strawberry Fields memorial for John Lennon, La Santa Cecilia did an encore of their version of the classic Beatles’ tune, rewritten with migrant workers in mind.

By the time Juana Molina came on, the sun was beginning to cut through like it does in the Caribbean. I’ve always admired musicians working with toys and just letting their inner utterances out. Here was Juana, jumping, smiling, tugging at the keyboard, guitar and tape loops, looking for a rhythm in the repetition. She smiled as if in a trance, yet focused on a rhythm. It was the dream space that held the drifting spirits of creativity, that spark that invites you to an out-of-body experience.

But here, with Juana, it was somehow all about the body. “Thank you for melting for us,” she said in English, confidently, and turned to her electric piano.

“ONE DAY/UN DÍA ONE DAY/UN DÍA ONE DAY/UN DÍA ONE DAY/UN DÍA!”

Her voice reverberated, scattering itself all around the park, seemingly a yearning without end. She was telling us that something new and unexpected was happening, that it was no coincidence that later that night, Romeo Santos, with his urban bachata universal matrix for pan-Latino falsetto balladry would fill Yankee Stadium for the second night in a row.

She was a wailing siren, a mixed messenger and her message was that the day, that one day, had arrived. Que el día ha llegado.

Ed Morales is a freelance journalist and author of Living in Spanglish (St. Martin’s Press). He teaches at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race.