While children have been fleeing poverty and violence in Central America for years, in 2014 the number of unaccompanied migrant children apprehended at the U.S./Mexico border reached an astonishing peak. By the end of fiscal year 2014, the U.S. had apprehended over 68,000 children at the border, resulting in a media and political maelstrom. Given that the U.S. Border Patrol recently reported a dramatic drop in the number of unaccompanied migrant children detained at the U.S./Mexico border, it might seem like the crisis at the border has ended. Certainly, a 51% drop since last year is significant, and some media sources have lauded the U.S. government’s collaborative efforts for resolving what President Obama referred to as an “urgent humanitarian situation.” Yet, after speaking with unaccompanied migrant youth in Mexican immigrant detention centers this summer, we’re far from convinced. In fact, the ‘urgent humanitarian situation’ is nowhere near resolved; it’s merely shifted south of the U.S./Mexico border where children continue to be detained and deported at an alarming rate. Rather than solve the ‘crisis at the border,’ the U.S. has elected to outsource immigration enforcement to Mexico instead.

We met Oswaldo, a 16-year-old Honduran boy, in a Mexican youth detention center less than a kilometer from the U.S./Mexico border. As a bi-national team of researchers, we were conducting interviews, surveys, and participatory workshops in Mexican immigrant detention centers in Tamaulipas to gain a better understanding of youth experiences with migration, detention, and deportation. In one of our workshop exercises, we asked youth to complete a life timeline, noting their most significant life events. The timeline below is Oswaldo’s:

1998 – I was born in Honduras

1 year old – They killed my father

4 years old – They killed my grandfather

5 years old – They killed my uncle

7 years old – I went to school

8 years old – They killed my other uncle

8 years, 9 months – They shot my uncle

13 years old – I graduated from 6th grade

14 years old – They killed my uncle

15 years old – They shot at me

16 years old – We moved in with my uncle

16 years old – I left for the United States

16 years old – I will be deported to Honduras (by Mexico)

16 years old – I will travel to the United States again

Oswaldo’s young life has been shaped by death, violence, and now migration; yet his timeline is unremarkable when compared to those of his peers. Many of their timelines also highlight migration, death, and violence as the dominant themes of their young lives. For instance, Evelin left Honduras because she’s 7 months pregnant, and the father of her unborn daughter has threatened to kill her, and her baby. She’s 15 years old. Daniela is a bubbly 13-year-old who fled El Salvador because the MS-13 gang, one of the most notoriously violent gangs in the region, is recruiting her quite aggressively. Plus, her mother, father, and 6-year-old sister live in Baltimore. When we asked her about her family she said, “I only really know them from photographs.” She’d like to get to know them in person. César, 9, left El Salvador after his parents were murdered and his grandmother was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He was travelling to the U.S. border with his 11-year-old cousin when he was caught. César believed he was in detention because, “there is no one who loves me” (Photos 1 and 2).

If these stories sound familiar, it’s because they are. Like the migrant children from the so-called surge at the border last summer, Central American children continue to flee extraordinary violence and poverty as they migrate north to reunite with their mothers, fathers, and extended family members in the United States.

While the crisis in Central America is in no way over, the situation has changed for these children. Over the past year, it has become increasingly difficult to make it to U.S. soil. No matter if these children have compelling cases for asylum or family reunification, they are being denied the chance to even get to the border to present their cases to U.S. officials. This is because in June of last year, President Obama met with Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto to develop a collaborative immigration security plan designed to strengthen Mexico’s immigration enforcement. In July 2014, Mexico implemented Plan Frontera Sur, a comprehensive strategy to increase border security, especially in Mexico’s southern states. To support Mexico’s heightened immigration enforcement, the U.S. has donated millions of dollars in mobile security and surveillance equipment, as well as communications equipment, training, and support.

Trains have sped up, too. In an effort to deter migrants, the rail companies have pledged to triple the speed of the trains. We don’t need to spell out what this means for children willing to take huge risks to reach the United States. As a further deterrent, rows of concrete pillars now stand along popular boarding areas to prevent migrants from running alongside the trains as they try to hitch rides. More menacingly, armed guards stand atop the railcars to scan for possible boarders. The Federal Police, joined by Mexican immigration agents, also patrol the trains, detaining or, in some cases, extorting anyone lacking legal papers.

To evade capture, some migrants are choosing more remote, and possibly riskier, routes. Much like what happened with Operation Gatekeeper in the U.S., when increased border fortification pushed people further into the deserts and mountains where they face higher risks of death and exposure, Plan Frontera Sur is pushing Central Americans further into Mexico’s harsher terrains. Some of the children we spoke to said they walked for hours to evade increased security checkpoints. They said they hiked across mountains and traversed deserts, often walking without water or without food. When we asked Oswaldo if he received any assistance on his journey, he responded very emphatically, that, no, he received no help from anyone.

But despite enhanced border fortification and increased immigration enforcement through Plan Frontera Sur, some kids are getting through to Mexico’s northern border. For the most part, these are children whose families can borrow enough money to pay a guide, or coyote, to take their children across the border. The higher the price, the faster and more comfortable the journey. In fact, some pay up to 10,000 U.S. dollars per child, a price that often includes multiple border crossing attempts. Travel by bus, van, and car are most popular, although some children, like Scarlet and Ysis, still get packed into cargo trucks.

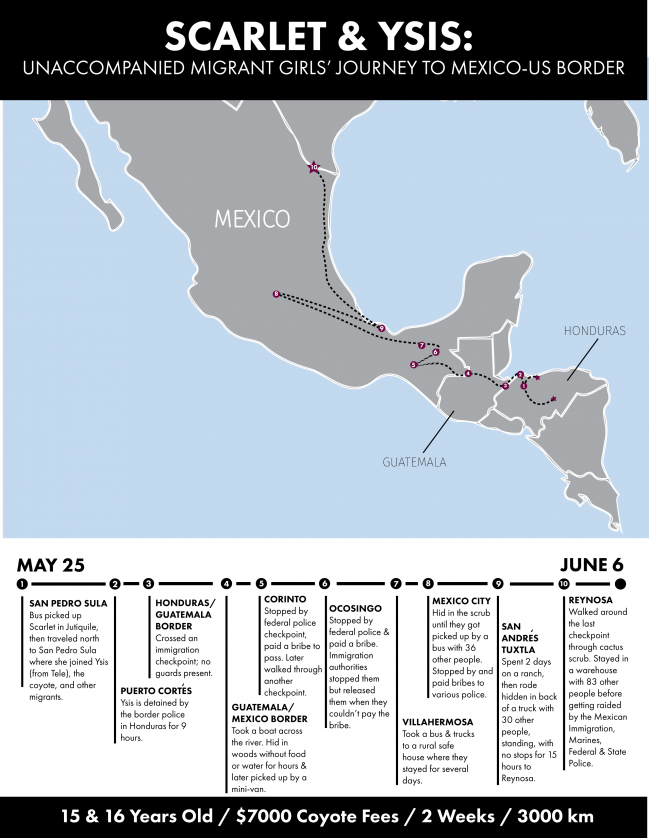

Scarlet and Ysis, 15- and 16-year-old Honduran girls, described their journey to the U.S./Mexico border in detail (Map 1). While crossing the Guatemalan border into Mexico wasn’t too difficult, they said that the number of immigration checkpoints increased as they travelled further north into the state of Chiapas. Having money definitely aided their journey. Although they bribed the Federal Police at the first two checkpoints, their coyote told them to sneak around the third on foot. When they ran into immigration agents, they hit a lucky break; although the agents demanded bribes, Scarlet and Ysis told them they were low on cash. For some reason, the agents let them through with the words, “Vayan con Dios” – Go with God. But, unfortunately they didn’t get very far, as they ran into another Federal Police checkpoint shortly thereafter. More bribing ensued. The next police checkpoint was in Mexico City. More money exchanged hands. For the next leg of their trip, they were packed into the back of a truck with a large group of migrants for a full day (without food or water). When they arrived close to Reynosa, they hiked through a cactus-filled scrub to evade what was meant to be their final checkpoint before crossing the U.S./Mexico border. In the end, only a stone’s throw from the U.S. border, Scarlet and Ysis were caught by state, federal and immigration authorities in a large migrant warehouse raid. The total length of Scarlet and Ysis’ trip was almost 3,000 kilometers.

Like Scarlet and Ysis, most of the youth we spoke to reported paying bribe after bribe to the Federal Police—and in some instances immigration agents—to pass through security checkpoints along their journeys north. Yet their bribes stopped working once they arrived within kilometers of the U.S./Mexico border. With the exception of a few cases, most had been caught on night buses. Some expressed deep regret, saying they simply didn’t have enough money left to bribe the immigration agents. Oswaldo’s comment was, perhaps, the most insightful. He said the immigration agents laughed at his proffered bribe, replying “The gringos pay us to catch you.”

After being caught, Central American youth are held in government run detention centers for migrant youth while Mexican immigration authorities begin deportation proceedings. Mexico now detains more Central American migrants than the United States. Recent figures reveal that while the U.S. detained 70,226 “other than Mexican” migrants (mostly from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador), Mexico apprehended 92,889 Central Americans between October 2014 and April 2015. This is a dramatic reversal from previous years, thanks to U.S. pressure on Mexico.

Conditions in some centers are better than others. Originally established by Mexican social service agencies to attend to needs of youth living in the border area, the detention centers for unaccompanied migrant children are designed to run like shelters. Some have youth programming and services, such as arts and crafts, or psychological counseling. Others offer very little. In one of the shelters we visited, children were never allowed outside and were confined to the same two rooms for months. The reasoning offered by shelter staff for this extreme form of detention was security. Indeed, we observed evidence of organized criminal activity just outside the premises of more than one facility.

For those in shelters lacking youth programming, time in detention can be mind numbing. And detention without any social or psychological services can be extremely detrimental for children who have suffered trauma before or during migration. Some of the children we interviewed had been in detention for weeks and were struggling—mentally, emotionally, and physically—with little to occupy their time other than television. They also had to grapple with the reality that, ultimately, they would be returning to the situations they tried so hard to leave behind. In the end, all of the children profiled in this piece were deported from Mexico.

At one of the detention centers, we conducted a workshop exercise with youth between the ages of 13 and 17 where we asked them to list the risks they might face after being deported back home. We worked with 6 girls and 5 boys from Honduras and El Salvador. Three small groups came up with the following list of compiled risks:

1. Death

2. Murder

3. Rape

4. Injury

5. Abuse

6. Beating

7. Kidnapping

8. Travel Accident

9. Forced to Sell Drugs

10. Forced to Join a Gang

A group of three boys also wrote that they might be killed by their enemies upon return, or they might return home to discover that one of their loved ones had been killed. The group of four girls – the only all-female group – included rape on their list. These are grim risks to return home to, and, unfortunately, their fears are not unfounded. In fact, at the end of June, a 14-year-old Honduran boy was murdered 3 days after his deportation from Mexico. The El Eden repatriation center in Tegucigalpa dropped him off at his mother’s house earlier in the day; at 11:45pm that night, two hooded men broke down the door to shoot Gredys Alexander multiple times.

We also asked youth what they planned to do post-deportation. While many said that they would be happy to see some of their friends and families again, 78% told us that they intended to pack their bags for the U.S./Mexico border almost immediately (Photo 3). In fact, some of the youth we met were already on their second or third border crossing attempts. In interviews and in our workshop, many youth insisted that they would keep trying to get to U.S. soil in order to claim asylum or obtain legal status, no matter the risks along the way. For these children, the risks at home are so much greater. Oswaldo explained the drive to keep going north: “Look, you go so many days suffering from hunger, freezing, suffering from thirst. But you’re so excited; you’re going north. It doesn’t matter that you’re suffering from the cold, hunger, nothing matters. You’re excited; you’re going to the United States!” These are children, many of whom haven’t seen their mothers and fathers in years; many of whom have suffered terrible tragedies; and many of whom are, perhaps, fatefully optimistic that their lives will improve exponentially once they make it to U.S. soil. Others, tired and demoralized, resigned themselves to the risks of remaining at home to face the violence they fled. Seventeen-year-old Salvadoran Yoshua explained that, after being in detention, “I don’t feel like trying again. And if they (the gangs) kill me there, at least I die in my country.”

In June 2014, when President Obama spoke about this “urgent humanitarian situation,” he said that the U.S. is committed to “fulfilling our legal and moral obligation to make sure we appropriately care for unaccompanied children who are apprehended.” But over the last year, the U.S. has managed to outsource immigration enforcement to Mexico in order to keep migrant children away from U.S. soil. The vast majority of detained Central American children we spoke to in Tamaulipas described well-founded fears of persecution that could make them eligible for refugee status under the UN Refugee Convention. But because of heightened U.S.-backed immigration enforcement in Mexico, many of these children cannot make it to the U.S. to claim asylum or file for legal status. Keeping migrant children from reaching American soil releases the U.S. from any responsibility regarding their safety and welfare, even though the precarity of their situation remains. They are beyond U.S jurisdiction, so they are no longer the U.S.’s concern.

Migrant children could file for political asylum in Mexico, but doing so is complicated in practice. To begin with, asylum cases take time to process, and youth must wait in detention until their cases are resolved, which is a significant deterrent. Approvals are also low. According to data released by Mexico’s Commission for the Assistance of Refugees (COMAR), only 21% of applicants received asylum in 2014. Youth told us about children who had remained in detention for months awaiting asylum hearings, only to be denied and then deported. Scarlet left Honduras because her ex-boyfriend, a gang member, tried to kidnap her. She explained, “I’m afraid to go back home, but I didn’t want to say anything [to Mexican immigration agents]… I don’t like it here. I’d rather be with my family.” Instead of risking a prolonged detention, with a slim chance of actually attaining asylum, many youth choose immediate deportation so they can quickly travel to the U.S. border again.

By outsourcing immigration enforcement to Mexico, the U.S. may have ‘solved’ the urgent public administration crisis on the border, but the urgent ‘humanitarian situation’ continues. The U.S. cannot ignore its complicity in the Central American migrant crisis. Through decades of economic and political intervention in the region, the U.S. has contributed to vast inequalities that shape all aspects of Central American children’s lives, at the same time that drug consumption in the United States fuels and funds much of the region’s organized crime and violence. Child detention is not an effective solution for young people fleeing desperate situations; rather, it only serves to further traumatize youth. Moreover, deporting children to unsafe situations cannot be considered a success. Doing so merely pushes them into cycles of repeated migration, or even worse, into the hands of their tormentors. Ultimately, by outsourcing enforcement to Mexico, the U.S. is turning a blind eye to thousands of asylum-seeking children who continue to flee violence in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. This does little to address the root causes of migration, and raises serious concerns over child refugee rights and welfare.

Kate Swanson is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at San Diego State University.

Rebecca Torres is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas-Austin.

Amy Thompson is a Doctoral Student in the School of Social Work at the University of Texas-Austin.

Sarah Blue is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at Texas State University.

Óscar Misael Hernández Hernández is a Research Professor in Anthropology at COLEF-Matamoros.

Support for this research was provided by the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin from funds granted to the Institute by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; the C.B. Smith, Sr. Centennial Chair Emeritus in United States-Mexico Relations #1, Dr. Bryan Roberts; the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of Texas at Austin; a Research Enhancement Grant from Texas State University; and a University Grants Program Award from San Diego State University.