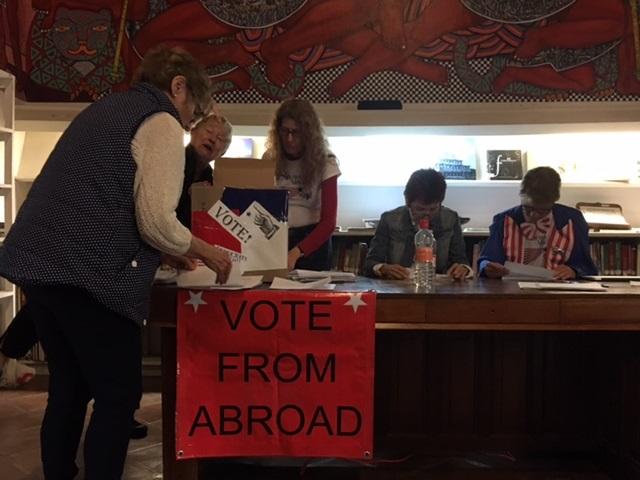

As voters across the country, from Alabama to Wyoming, lined up on Super Tuesday to cast ballots in the U.S. Presidential primary, so too did an enthusiastic crowd of Americans living far south of any U.S. polling station, in the arid mountains of San Miguel de Allende [SMA], Mexico.

March 1, 2016 marked the third time, since 2008, that registered Democrats living outside of the U.S. have been able to participate in a “Global Primary.” They do so not only by submitting votes via post, fax, and email, but also in person at over 100 official voting centers in more than 40 countries around the world. Democrats Abroad, an official arm of the Democratic Party, sponsors the Global Primary. As Marc Berube, National Vice Chair of Democrats Abroad Mexico explained, the San Miguel de Allende chapter is the largest and most active in Latin America. In 2008, during a tight primary race between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, voter turnout among Democrats in San Miguel was the third largest in the world, just after London and Paris.

Final data on 2016 global voter turnout are not yet available, but Berube, and “Get-Out-The-Vote” Chair and National Executive Committee member Ellie Yepez, expect an equally impressive showing for SMA this time around— and the steady stream of U.S. citizens arriving at the Bibiloteca Pública throughout the day Tuesday suggests they are right.

Democrats Abroad enjoy “state-like” status within the U.S. Democratic Party, guaranteeing them representation on the Democratic National Committee and at the party’s national convention. Come July of this year, from the convention hall in Philadelphia, representatives drawn from U.S. Democrats living around the world will stand up, just after the state of Delaware, to allot their 17 votes toward the party’s nominee—undeterred, and in some instances inspired, by that fact that many live permanently outside of the U.S. and have done so for decades. (To date, the Republican Party has not granted the same formal voice to Republican voters abroad.)

A growing population of U.S. citizens living abroad and their cross-border mobilization on Election Day attest to reconfigurations in conventional models of political and cultural belonging. They also beg important practical and philosophical questions about citizenship and democracy in a global era.

Recent estimates put the population of U.S. citizens residing abroad at more than 8.7 million. Mexico is home to the largest proportion of that population, and San Miguel de Allende ranks among the top settlement sites for U.S. citizens living in Mexico. Those who have moved south of the border have done so for a range of reasons. Some are professionals employed by the many transnational corporations that have set up shop in Mexico, particularly since NAFTA. Others work for international governmental and non-governmental organizations. An increasingly large number, particularly in locales like San Miguel de Allende, are retirees. These U.S. baby boomers say that a variety of factors motivated their migration (climate, culture, wander-lust, among others). Consistently topping the list of reasons, however, is the ability to enjoy a standard of living in Mexico that is far above what their income would afford in the U.S. San Miguel is home, or second home, to well-heeled U.S. citizens, to be sure; but many of the resident gringos are living (albeit quite comfortably) on U.S. Social Security. For this latter group, the economic factors that pushed them to cross the Rio Grande range from the increasing costs of health care and prescription drugs in the U.S. to vulnerable pensions and sub-prime mortgages. These factors have had significant influence on their decision to vote, and for whom.

Financial concerns have also increasingly become a factor in why these citizens tend to vote abroad vote. When asked about their motivations for voting, oft mentioned is recent U.S. legislation, such as the 2010 Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act [FACTA], that many perceive as imposing undue regulatory burdens on citizens living outside of the U.S. The Act is intended to eliminate tax fraud, but large U.S. expat interest groups with investments abroad contend that increased regulations on the part of FACTA have led to restricted banking services for U.S. customers overseas. However, in SMA, where expats continue to buy up large colonial homes in the historic city center, U.S. citizens seem to be largely unencumbered by such tax issues.

Demographic, economic, and technological trends are poised to further expand the population of Americans living abroad in the coming years, just as the opposite trend appears to be occurring with regard to Mexican migration to the U.S. The silver tsunami of retiring baby boomers has just begun its rise; macro- and micro-level indicators in the U.S. suggest on-going financial fragility for U.S. seniors, among others. In addition, a booming online media industry, dominated by magazines like International Living, slickly markets the benefits of moving abroad, and facilitates the process of doing so. Interested readers receive daily emails promising “low cost living” and “lollygagging lifestyles.” Some longer-term North American settlers in SMA resent the recent arrivals drawn primarily by the chance to live what AARP magazine somewhat offensively described in 2004 as the “La Vida Cheapo.”

The bulk of U.S. emigrants will continue to settle in the Americas—as is already evident in the growing popularity not only of towns like San Miguel de Allende and Lake Chapala in Mexico, but similar sites in Panama, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Belize. As this population of Americans abroad grows, so too will the size of the U.S. global electorate and the related lobbying efforts of a growing number of interest groups and organizations, including Democrats Abroad, Republicans Overseas, American Citizens Abroad, the Association of Americans Resident Overseas, and the 25-member bipartisan Americans Abroad Caucus in the U.S. Congress.

The implications, then, of the expanding practice of extra-territorial citizenship are worth pondering. So is the obvious, but too rarely acknowledged fact that native-born U.S. citizens are migrants too—often in to countries whose own nationals have often been treated inhospitably in the U.S. – characterized, for example, as criminals and rapists by a current front-runner in the U.S. presidential race.

Notable this year were the number of U.S. citizens who showed up to vote in SMA on Super Tuesday as a way of expressing concerns about the political discourse and general current state of affairs in their homeland.

“People are excited about the Democratic candidates,” Ellie Yepez explained, “but they are also concerned about Trump. This [talk of building a wall] is a sensitive issue, particularly in Mexico, and as Americans, it’s embarrassing.” When I asked Kathleen Walsh, a native of Minnesota, what was motivating voter enthusiasm in SMA, she echoed Yepez: “His name is Trump!”

Immigrants within the U.S., particularly those from Mexico, who remain politically engaged with their country of origin raise their eyebrows about the U.S. citizens living in their own home countries, who question whether they should continue to have the same voice in the affairs of the U.S. while living abroad. Meanwhile, these migrants’ peers who stayed behind often question if those who leave should continue to have the same voice in the affairs of the nation-state as those who do not. Democratic theorists debate these questions in terms of ‘stakeholder’ status, but significant policy implications arise as well.

Americans abroad have lobbied, for example, to have Medicare cover expenses in their countries of settlement. And in the case of Mexico, this proposal involves the added complexity of arguably extending these benefits not only to U.S. citizens who retire abroad, but also to Mexicans who lived and worked in the U.S. as permanent residents, but then returned to Mexico. Current calls to extend the U.S social safety net across the southern border come from native-born citizens, as well as Mexican-born permanent residents of the U.S. who paid Medicare taxes for the required 40 quarters, but are currently unable to reap the benefits of their labor.

For the U.S. expats living in Mexico, a group increasingly comprised of retirees looking to capitalize on cheaper living costs, a strange dichotomy emerges: while U.S. citizens living in places like San Miguel de Allende exercise their U.S. political rights, U.S. elected officials and presidential candidates threaten to strip immigrants inside the borders of the U.S. of the limited protections they so tenuously hold. Many of the voters showing up on Tuesday in San Miguel de Allende hoped that their votes could help assure that the next president won't further erode them.

Sheila Croucher is a University Distinguished Professor of Global and Intercultural Studies at Miami University in Ohio. She is the author of The Other Side of the Fence: American Migrants in Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2009) and Globalization and Belonging: The Politics of Identity in a Changing World (Rowman and Littlefield, 2004).