Jean Claude Fignolé was born in 1941 in Abricots, Haiti. During the 1960s, he co-founded the Spiralism movement with Franketienne and René Philoctéte. At the height of the authoritarian regime of Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier, the Spiralists made an intellectual point of refusing to associate exile with freedom and treating political issues and violence symbolically in their works. Although Spiralisme, which rejects realism and embraces disorder, is well known in the Francophone world, little of it has ever been published in English. About the movement, Franketienne says, “Spiralism defines life at the level of relations (colors, odors, sounds, signs, words) and historical connections… Spiralism uses the Complete Genre, in which novelistic description, poetic breath, theatrical effect, narratives, stories, autobiographical sketches, and fiction all coexist harmoniously.”

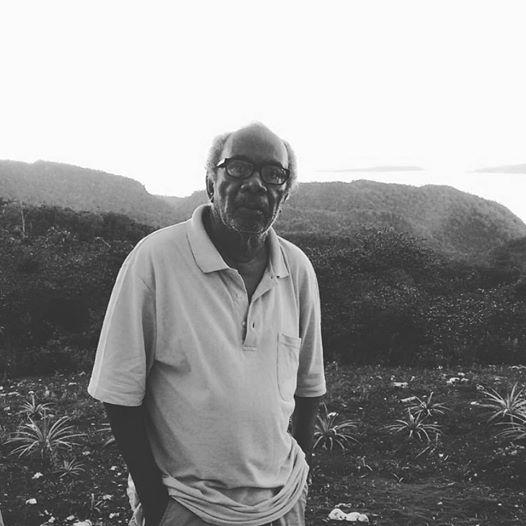

Les Possédés de la pleine lune (Demons of the Full Moon) (Paris, Seuil, 1987), a novel about a woman who was descended from a fish is considered to be one of the finest of Fignolé's 13 books. In 2007, he was elected mayor of his hometown of Abricots. He made progressive advances in reforestation and social justice issues, though these efforts were partially hampered by the refugee crisis that followed the Port-au-Prince earthquake of 2010. After his term ended, Fignolé moved into a small stone house on top of a cliff above Pestel. I spent two days with him there in April 2016. On the second day, after waking up at 4:30 AM, spending several hours answering different political phone calls, and then meticulously going over my questions and taking notes, he granted me an interview. What follows is an edited transcript of that interview. (For video of the full interview, please click here).

Brian Mier (BM): What was it like when you were a young man in Abricots?

Jean Fignolé: (JF): It was a very normal village life, similar to that of any other village, though we did have to be aware of natural phenomena, given that hurricanes struck every two to three years. This generated a sense of solidarity and community. I would even say a sense of common destiny, in fact—reinforced by the familial bonds that most of us shared. The impact on my character was to develop, from a very young age, a sense of closeness in terms of my relations with others, a sense of solidarity. It taught me that we live “together,” and we have to strive to make this “living together” a success through solidarity and sharing.

This reminds me of the holidays, in particular during the breadfruit harvest, when the fish were plentiful and the whole village would celebrate. During this time, food was prepared in every household—a veritable feast—and anyone could walk into any house and be served food because we shared everything.

BM: How did you become involved with the formation of the Spiralist Group?

JF: Very simply in fact… At the time the dominant literary current was composed of the indigenism, which had run its course. In the Caribbean and in Africa, the negritude current was marching on triumphantly—although it was denounced as racist by its detractors. At the same time there was a literary movement in France known as the nouveau roman (new novel), which claimed to shatter the presence of a direct subject, or central character, in the novel, thereby disconnecting the account of the story with its principle subject. This led to an explosion within the traditional form of narration to the point that the death of the subject within it was proclaimed.

At this time [the late 1950s early 1960s], we were also witnessing the emergence of the “Third World” between the two hegemonic blocs of world domination, i.e. capitalism and communism, wherein space for the emergence of a “Third World Man” was created and allowed to emerge. We in Haiti, therefore, decided that we could not accept not being actors, not being central characters. In addition, we decided this affirmation as not only relevant to just any story, but was principally pertinent to a story that could be created and written together. It is at this moment that we decided together that the death of the story's central character implied, from a historical perspective, the death of the Third World Man as a central actor.

So it is between the two postures, i.e. the explosion of the narrative and the death of the subject, that we decided to maintain the explosion of the narrative in accordance with its correspondence to Afro-Indian [i.e. indigenous American] storytelling traditions, while rejecting the death of man in order to affirm our presence as historical actors. From this perspective, Spiralism leaned on Third World ideology based on the solidarity of the Third World to the “exploited man,” and as such, it was grounded philosophically in a Marxist current derived from the fact that all young Haitian intellectuals of the day were from the Left.

BM: How does Spiralism relate to Haitian and Caribbean cultural traditions?

JF: As already stated, in Haiti indigenism had already run its course. We were also cautious with regards to the negritude movement despite the universality of [movement leaders, poets and politicians] Aime Cesaire and Leopold Senghor, precisely because its detractors expressed concern over the temptation of anti-white racism expressed as the right to culture based on the Negro premise. So we searched and we searched. And we discovered, in order to link Spiralism to other Caribbean currents, it was necessary to link it to the traditions of Afro-Indian storytelling due to their exploded narratives or what we called “total narratives,” meaning the capacity to simultaneously be a novel, poetry, music etc…encompassing everyone in the narrative follow through.

But if we are to link Spiralism to its antecedents, then we must also look to the movement developed in Veracruz [Mexico] known as la ronda which premised that art itself was of circular form and movement. In addition, there was the Guatemalan author, Emethias Rosotto, who wrote in his novel Mr. General that art could only be spiral. This formula worked for us, because our writing style is spiralistic and not linear. As we write, we turn and we turn and we can embrace all as we turn.

BM: Does Vaudou have an influence on Haitian Culture?

JF: For the most part we are a people of African origin, brought to these shores under the conditions that we all know. The various tribes arrived here with their own distinct cultural packages including religion, customs, art, etc… but they were able to find a unifying factor despite the fact that they were from different and sometimes antagonistic ethnic backgrounds. Vaudou was that unifying factor and served as the ferment of resistance of slaves vis-a-vis the hell of colonial existence.

We know that the Bois Caiman ceremony served as the foundational act of liberation from slavery. We therefore find that the influence of Vaudou crosses the entire spectrum of Haitian life. Several attempts to eradicate Vaudou, even by [independence leader] Toussaint Louverture himself, led to a form of resistance known as marronage wherein Vaudou, rather than disappear, was able to infiltrate Christianity, assimilating certain rhythms and rites to form an identity that was nothing less than a mask. Vaudou gods and laws hid behind Catholic saints, for example—Saint John became none other than Ogou Ferail, the metal god.

This continued after independence as Vaudou became intimately intertwined with every articulation of Haitian life… There is no political life in Haiti without Vaudou. Same goes for cultural life where the Vaudou imprint is increasingly clear. In works of art, on canvases, you can feel the presence of Vaudou. This is true even within the church, where Vaudou rites are increasingly adopted in religious song. The end result is that Vaudou is in the process of colonizing Christianity rather than the other way around.

BM: Has the dynamic of Vaudou changed with the spread of evangelical religions in Haiti?

JF: As I have said, Vaudou finds itself manifested in every articulation of Haitian public life and particularly in political life. There is no doubt in my mind that Vaudou is influencing both Catholicism and Protestantism, because they have not been able to make it disappear, given that it is strongly ingrained in the Haitian conscience. Increasingly, what we need is a greater willingness by cultivated and wise Vaudou practitioners to affirm themselves publicly and denounce the practice of the religion as something secretive. The more they affirm themselves, the more they will be listened to, particularly in the political arena. There is a deep wisdom in Vaudou which we do not listen to and which we do not utilize effectively. For example, there is a Vadou saying which states: “The wrong committed by one man is suffered by all men.” If we were to listen to this message, we would understand the need to avoid wrongdoing in order to avoid inflicting pain on humanity. So, in that sense, there is a Vaudou morality, which eventually should find its rightful place next to Catholic and/or Christian morality with enough power to shake up political morality in this country [Haiti].

BM: What are your views about the arrival of evangelical religions in the country and their impact on all forms of culture, not just religious culture? Is this a form of neo-imperialism or neo-colonialism?

JF: In Haiti, evangelical churches base the premise of their action on one principle, on one element: Hunger. In other words, the vulnerability of Haitians’ living conditions. They are therefore able to “recruit the faithful” not on the basis of the strength of their convictions, but on the basis of their capacity to feed the recruited. There is no doubt that this form of evangelization, i.e. the evangelization of conscience through the evangelization of the stomach, is perverse. Its impact is that the Haitian man no longer seeks to form an opinion. Rather… he blindly follows the diktats of the congregation as a function of what the church proposes in terms of improvement to his living conditions.

While we must recognize that evangelicals do a certain amount of work in education, it is unfortunately mostly a brainwashing. They teach children to permeate themselves with the slogan that is on American cash: “In God we Trust.” The notion is thus perverted to become… “In the dollar we trust” and “in the white American we trust.”… [T]hese churches, rather than observing their evangelization and education mission, are implementing U.S. foreign policy in Haiti. This is why they manipulate political crisis. They manipulate economic crisis. They manipulate everything in Haiti.

Brian Mier is an editor at Brasil Wire and a freelance writer and producer based in São Paulo, Brazil.