For communities living in rural areas under the dominion of Colombia’s oldest guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the June 23 announcement of a cease-fire agreement has been met with concern and hope. The final accord, which President Juan Manuel Santos has announced will be signed on July 20, Colombia’s Independence Day, aims to bring the longest running guerrilla war in the hemisphere to a close, ending a violent conflict that has left hundreds of thousands dead, 42,000 kidnapped, and as many as seven million Colombians displaced.

Yet many fear that this end to the war will not mean an end to violence, and that these remote regions will be finally fully incorporated into Colombian political and economic life.

On June 23, six days before the agreements were announced, I traveled to Puerto Leguizamo, the municipal capital of the southernmost municipality in Putumayo, a small state along the Ecuadoran border that has been an epicenter of political violence and the illicit drug trade throughout the Colombian conflict.

The 32nd Front of the FARC settled in Putumayo in the early to mid-1980s, while they were still a marginal group with a minimal national presence. Putumayo was logistically important for the FARC because of its shared border with Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil. The FARC encountered minimal state resistance and found a ready base of social support in the growing population of colonos (peasant settlers), many of whom had lived under guerrilla leadership in other rural areas.

FARC commanders came to control much of the social and economic life of the region, maintaining a strong militia presence in hamlets and town centers and regularly patrolling rural areas. They used their military power to mediate disputes and enforce local contracts, as well as to organize community improvement projects.

In the 1980s, U.S. counternarcotics interdiction efforts targeting the small planes bringing coca paste from Bolivia and Peru into Colombia pushed coca growing into historical strongholds of the FARC. In the 1990s, Putumayo reportedly produced 50% of the world’s coca paste, the key ingredient of cocaine, for the international market, attracting migrants from neighboring regions fleeing political violence and searching for economic opportunity.

As the extravagant resources of the coca trade became more widely known, the FARC expanded its “taxation” system to include coca, first collecting taxes from the middlemen and traffickers, and then from the peasant farmers themselves. This tax was known as the gramaje—a price per gram of coca paste, and nowhere did the gramaje come to dominate local economic relations as it did in Putumayo. The FARC’s Southern Bloc became one of the most powerful guerrilla units in the country, operating with multiple fronts and able to mobilize thousands of combatants, as well as urban militias based in small towns.

FARC efforts to regulate local life were clearly evident during my first trip to the region in 1999. The local activists who helped organize the trip had to request permission from the regional commander for our travel by boat down the Putumayo River, from Puerto Asís to Puerto Leguizamo, and we only proceeded after given clearance. We did not stop in particular hamlets where local commanders were known to be mercurial.

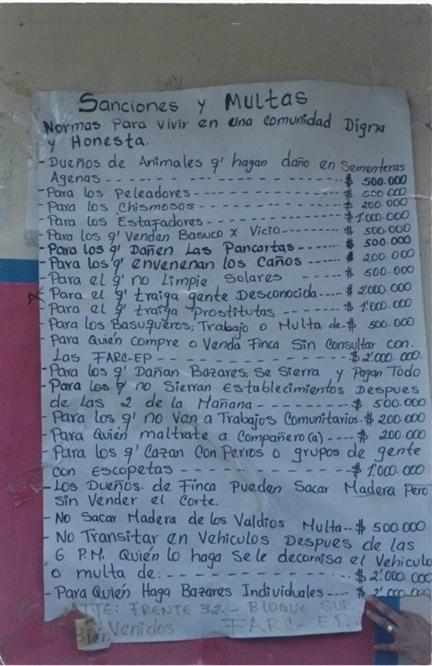

During that visit, I passed a large, slightly tattered poster attached to the wall of a concrete community building: “Sanctions and Fines: Norms for living in a dignified and honest community.” Signed by the 32nd Front of the Southern Block, the poster listed nineteen regulations and the corresponding fines and punishments for violations, ranging from 200,000 to 2 million pesos (approximately US$100 to US$1,000). The crimes ranged from gossiping (US$100 fine) to the more serious violations of bringing unknown people into the region (US$1,000), selling a farm without consulting with the FARC, or traveling in a vehicle after 6 p.m., which also could result in confiscation of the car.

Life in Putumayo has definitely been transformed since that first trip. Between 2000 and 2005, the region was an intense conflict zone, disputed between FARC guerrillas and paramilitary forces working with local military commanders.

Putumayo was also the centerpiece of Plan Colombia, a USD$1.2 billion dollar aid package passed in 2000 that has added up to over USD$9 billion in U.S. assistance since. The bulk of the initial package – $600 million – was destined for the “Push into Southern Colombia,” used to train and equip three new counternarcotics battalions of the Colombian Army and fund fumigation programs (aerial spraying of chemical herbicides intended to kill coca plants).

Beginning in 2004, Plan Patriota, an intense counterinsurgency campaign, weakened the FARC, its troop numbers diminished, leaders killed, and units forced into strategic retreat. Government investigators estimate that more than 3,000 people remain “disappeared” as a result of this fighting, most presumed to be buried in the regions many mass graves.

Since then, the FARC has no longer enforced a curfew or maintained roadblocks on the main roads. The state is investing in infrastructure, including a new airport and, for the first time, paved roads along many of the central arteries connecting the Ecuadoran border to the departmental capital.

Life in Leguizamo

Nestled between the Putumayo and Caquetá River, Puerto Leguizamo is Putumayo’s largest yet most sparsely inhabited municipality in the southern state of Putumayo, with a total population of approximately 30,000 people. About a quarter are indigenous, among them Huitoto, Coreguejes and Sionas living on 25 resguardos (indigenous reservations). The municipal seat, a small town also called Puerto Leguizamo, sits on the Putumayo River which also serves as the country’s national southern border with first Ecuador and then Peru.

I was traveling with representatives of the Alianza de Mujeres del Putumayo Tejedores de Vida (Alliance of Putumayo Women, Weavers of Life), who had organized a workshop with local women leaders on public policy and the peace process. Fatima Muriel, then a Department of Education Supervisor, was inspired to found the network in 2005 following workshops in rural conflict areas in which teachers and parents pleaded for support. She galvanized teachers and other women community leaders to develop survival strategies for women and communities during the height of the conflict. Forced to hold their organizing meetings outside the region in neighboring Nariño or Bogota, they provided a safe space for women to document the situation in their communities and grieve the violence against their families. They offered safe houses for women under threat, and intervened with local commanders to plead for the release of detained family members and neighbors.

As the levels of violence have declined, the Alianza has turned to a new challenge: organizing women’s participation in local politics. They began with workshops educating women about their rights, and about opportunities to shape local governments’ policies, particularly those impacting women and girls.

Like other national and international observers, women from the Alianza hope that the announcement of a detailed plan for the demobilization of the FARC will result in a final peace accord. On the day of the announcements, large crowds gathered to watch on outdoor TV screens on the Séptima avenue in downtown Bogotá, celebrating despite light rain, with tears and hugs for the possibility of a future without war. In the departmental capital of Mocoa, families gathered outside the Alianza office to light candles in support of peace.

The conversations with women in Puerto Leguizamo, however, pointed to some of the complexities of the process for those long accustomed to FARC dominion. The negotiators are clearly attempting to implement mechanisms to avoid the pitfalls of the previous failed negotiations between the government and the FARC in the early 1980s and the late 1990s, including a mishandled demilitarized zone and sharp increase in political violence targeting a legal political party affiliated with the FARC, the Unión Patriotica (Patriotic Union.) But how these efforts to demilitarize and demobilize play out for the group remains to be seen.

Challenges of Demobilization

The demobilization plan outlined in the June agreement requires the FARC to lay down their arms within six months. FARC troops will gather in eight encampments. After their weapons are handed over to the United Nations for destruction – some will be used to make peace sculptures for UN offices in New York, Cuba and Colombia— they will spend six months in 23 zonas veredas – each the size of a vereda, a hamlet or smaller. This process will be monitored by the United Nations and Latin American and Caribbean Community of Nations (CELAC).

This model clearly reflects lessons learned from the most recent failed process with the FARC. In 1998, then-President Andrés Pastrana agreed to a “zona de despeje” (demilitarized zone) in the Caguán, an area roughly the size of Switzerland. The government withdrew all military personnel, although civilian state officials continued to occupy the area and FARC troops were allowed to remain armed and in control of the region. Concerns about abuses in the region by the FARC, as well as ongoing combat actions, led to the rupture of the talks in February 2002.

Many in the Putumayo region – and across the country – are concerned that some remote rural fronts will not demobilize, particularly those who have established financially lucrative criminal syndicates involved in extortion, drug trafficking, and other illegal activities. Rumors that some commanders are telling their troops to stockpile weapons erupted in media accounts of the Frente 1 in Guaviare refusing to demobilize.

As the FARC does demobilize, the opinions of rural residents are divided about having their long-time guerilla neighbors now return home as civilians attempting to find jobs, land, and perhaps also political power. Among the women at the public policy and peace workshop, the issue of reconciliation was hotly debated.

One woman cried, remembering how a decade before the FARC shot her husband in front of her children, and her subsequent life as an impoverished single mother forced to flee her home. As the displaced mother of five children remarked: “I don’t want to have a guerrilla as a neighbor, after all the things that they have done... They say we should open our hearts to receive them, but I say send them to people who haven’t suffered like us. We are people that they hurt. My heart is full of rancor.” She was comforted by others in the workshop, who argued that Catholicism and the norms of local indigenous practices required forgiveness.

Who will reap the rewards of peace?

Some already living on the edge of the rural economy reject re-integration programs targeting ex-combatants, arguing that it is fundamentally unfair. “The government is going to give a good life to the guerrillas. They are going to go live in a palace, and the poor peasants will keep being poor,” one woman said at the workshop, echoing comments made by others. “They weren’t the ones who had to give up their children; and now they are going to come out the winners, (salir premiados.)”

The Obama administration has pledged $450 million in support of “Peace Colombia.” The Interamerican Development Bank, and the European Union have all pledged to support the Colombia peace process by financing rural development projects in areas hit hard by the conflict. But given dynamics of the current U.S. electoral cycle, falling oil prices, and the current crisis in Europe, such funding is unlikely to meet the demand of the millions of small farmers already struggling as they attempt to integrate thousands of newly demobilized ex-combatants into the rural economy.

One key issue is access to land, a deeply divisive issue in Colombia that in many ways set off the conflict to begin with. The FARC has proposed expanding the “peasant reserve lands,” a program designed to safeguard small-scale farmers by preventing land accumulation by single buyers in designated territories. Rural residents wonder where this land will be found. During the workshop, one Huitoto woman expressed the concern of many indigenous leaders: that indigenous reguardos, which now cover approximately 25% of Colombia’s rural land, will be particularly targeted as land to be demobilized.

The collective land rights of Afro-Colombian communities were granted by the 1991 Constitution may also be at risk. Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities have struggled to maintain autonomy from the guerrilla groups that move through their territory, often at great personal cost. At the end of June, indigenous and Afro-Colombian leaders traveled for the first time to Havana to present their concerns as community representatives before the negotiators. “They are going to go into our territory, and they [demobilized combatants] are going stay there, because this is the only land there is,” the same Huitoto woman said. “There is no territory available in the cities. Look how it will end, with them doing well and we will be the ones affected.”

Indigenous communities are worried about another peace dividend: increased international investment, including extractive industries, in rural communities previously inaccessible because of the conflict. In interviews in late June, local officials in the Puerto Leguizimo mayor’s office described the FARC demobilization as an opportunity for development. These officials pin their hopes on ecotourism projects focused on La Paya National Park, home to the famed Amazonian pink dolphins. Because of the conflict, the park has been little visited and without any infrastructure; the mayoral development plan feature ecotourism plans that locals imagine will bring much-needed jobs and investment into the region.

Oil companies are also hoping to gain peace-time dividends, as oil exploration has increased in the region as the violence has slowed. Yet local communities continue to fight for an alternative vision of what peace might look like. At the end of May, a Huitoto-Muiri community announced that they refused to approve any oil exploration on their land, as required by the prior consultation process (any development projects occurring on indigenous land must be approved by law through a collective evaluation).

Prospects for Justice

The peace deal promises a form of transitional justice that trades full confessions for limited sentences carried out in special “restricted” zones. Yet recruitment of minors, considered a crime against humanity and thus not part of transitional justice agreements, is one the thorniest issues for the residents of Putumayo and other states where the FARC has been dominant. Adolescents frequently joined combat units in their early teens, in in response to pressure or incentives from local commanders. Women told of allowing their children to join “voluntariamente por miedo,” (voluntarily because of fear) watching as they were offered enticements or promised a better life.

Demobilization also means the possibility of reunion with children who, coerced or persuaded, joined the FARC. I heard one such story from a man in a billiard hall in Tagua. His daughter had joined the FARC when she was just 14 years old, and he now has no idea where she is. His fervent hope is that following the peace accord he will be able to find her. “I will recognize her instantly,” the man told me, “because she has a scar on her face from a burn as a child.” After his daughter joined the rebel group, he fled his farm when he saw the local commander begin to ask his young son to meetings. His is a common story; many moved to avoid such recruitment, a form of displacement that is vastly uncounted in the official statistics since few were willing to list this as the cause, particularly those who stayed in Putumayo.

Politics in the New Colombia

While in power, the FARC commanders required rural residents to attend meetings, organized collective work projects, and policed remote communities. Many women I spoke with doubted that that the state would step in to fulfill the role the FARC played in local governance.

Sitting around a low table, one woman explained that her hamlet, the FARC maintained total control. “No one steals anything, you can leave your phone anywhere, no one will take it” – because they are afraid of the FARC system of justice, a three-strikes system in which warnings are followed by punishment, or death. “If these people will leave, the violence will be worse, because if anyone sees anyone with money they will steal it.” She is pessimistic about the process, doubtful that the government will replace the FARC’s harsh system with any functioning state presence. “Peace only exists for the cities, it will never exist for us in the campo.”

But prospects for peace means opportunities for new political organizing. The FARC leadership has insisted that they intend to form a political party and campaign for public office, although the mechanisms for special electoral designations have yet to be worked out.

Political organizing is difficult in rural areas, as communities live far from each other and from the rivers that serve as the major form of transportation. “All of that pedagogy for peace, teaching people that it is better to live without arms, how to resolve conflict without fighting, all that remains to be done. And the communities is where all that has to happen,” one community organizer told me. Today, there are more than 90 juntas de accion communal, or community action groups, that organize political participation at its most local level, whose elected officers work to channel state services. “About 30 aren’t legally organized, so we are trying to do that,” the organizer said. He described the difficulties of organizing in the region, because urban people are burned out and don’t see the point.

The Marcha Patriotica (Patriotic March), a political movement formed in 2012, has stated since their inception that they would welcome demobilized guerrillas into their fold. I spoke with one of their organizers in Puerto Leguizamo, who expressed his “total commitment to the life of struggle for those who have no voice, for my people.”

Marcha Patriotica activists have reported ongoing violence against them. The resurgence of paramilitary forces bring back memories of what happened to the Patriotic Union, a leftist party formed in the wake of failed peace talks with the FARC in the mid-1980s. After significant local electoral success, their membership was decimated by political violence, what the survivors call a political genocide.

The 23 zonas veredales will have four rings of security, the first provided by the United Nations, followed by three levels provided by Colombian state security forces. Yet the real security challenge will come after the desmobilizados leave the region and reincorporate into society.

The Long Road to Peace

Many details and drafts remain before the final peace agreement is signed. Despite international support for the process, Santos faces low levels of domestic backing, with less than 20% viewing him favorably according to national polls. The final agreement, once signed, will face a national referendum. While some polls show high levels of support for the process, as much as 70%, others point to the recent vote for Brexit as an example of how a general election can stymie a carefully brokered deal. Multiple campaigns for “vote yes” are already being launched to gather support for the deal.

However, criticisms spearheaded by former president Alvaro Uribe continue to work to undermine the deal. Uribe’s public Twitter feed continually critiques President Santos’ efforts. Uribe has organized marches against the process, as well as lobbying behind the scenes.

Yet giving up on peace is not an option for the people of Putumayo. As Fatima told me while we reflected on the workshop, “we have to celebrate this moment, it is a moment we have been dreaming of for many years. Peace has many enemies, but we are committed to peace, for our children, for our territory.” She went on, “when you are climbing a mountain, you don’t look up, or you will give up, discouraged. You just put your head down and keep walking.”

Winifred Tate is an associate professor of anthropology at Colby College. She is the author of Drugs, Thugs and Diplomats: US Policymaking in Colombia and the award-winning Counting the Dead: The Culture and Politics of Human Rights Activism in Colombia.