There is no doubt that the August 31, 2016 Brazilian Senate vote that impeached President Dilma Rousseff is a watershed moment for Latin America’s largest, most populous, and most economically dynamic country. It marks the end of thirteen and a half years of Workers’ Party (PT) rule. It also means a shift toward conservative social and economic policies that were prominent at the end of the twentieth century before Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the fiery trade-union leader, came to power in 2003. The Brazilian Left now faces major challenges about how to regain popular support, carry out an in-depth evaluation of its past mistakes, and successfully participate in electoral politics with a program that will address the country’s social and economic problems. At the same time, Lula, as he is popularly known, faces possible criminal charges that could cancel his plans for leading a Workers’ Party-led coalition to an electoral victory in the 2018 presidential race.

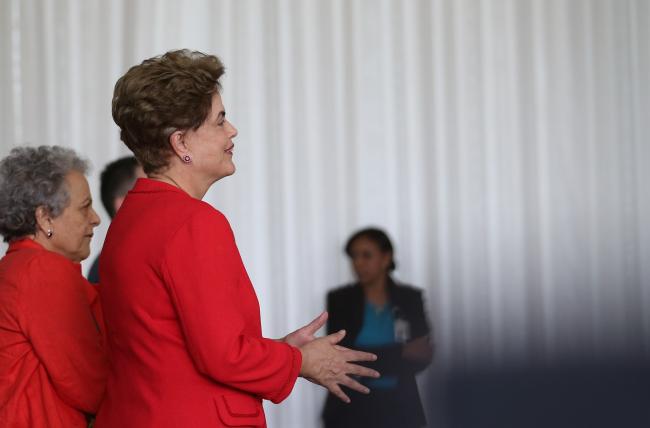

Based on accusations that Rousseff violated budgetary regulations, 61 Senators voted for her ouster, garnering a necessary two-thirds majority, while 20 other members of the upper house came to her defense. In a surprise second vote, the body rejected a proposal to take away her political rights for eight years, which would have precluded her from holding any government job or running for public office for a decade. In a defiant speech to her supporters the day of the impeachment, Rousseff denounced her removal from office as a parliamentary coup d’état and vowed to continue the fight for social justice in Brazil. She later announced she was moving to Rio de Janeiro, so that she could remain in the thick of political contestations against the new government of Michel Temer, her 2010 and 2014 vice-presidential running mate. The machinations behind the impeachment process are quite complex, so a bit of historical context is in order to understand both how the opposition managed to remove her from office and what might lie ahead for the country.

During the two-term presidency of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002) of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), the former sociologist stabilized inflation, encouraged foreign investment, and privatized many key state-owned industries. Still, by the end of his second term, unemployment had reached 12.5 percent and inflation had crept up to 12.8 percent, while economic growth averaged 2.3 percent annually. There was also popular dissatisfaction with many of his social measures, which lay the groundwork for a leftwing victory in 2002. In Lula’s fourth bid for the presidency, he cast off much of the socialist program of the Workers’ Party to assure the public in general, and especially entrepreneurs, that his administration was not interested in overthrowing capitalism, but only in trying to tame it.

The Brazilian Left, which ranges from neo-Marxists to European-style social democrats, has managed to capture approximately 35 to 45 percent of the vote outright during recent national elections, in coalition with centrist-leftist parties. The rest of the electorate is divided among an array of other centrist and right-leaning social democratic and conservative political parties. Election to the presidency requires an absolute majority of valid votes, and in the last four races, Lula (and then Rousseff) have had to face off against a united coalition of the center-right. In order to guarantee a majority of the popular vote and also secure a working majority in Congress, the PT has also had to build a governing coalition from among members of the country’s 32 different political parties, exchanging support for cabinet positions and political appointments in the government bureaucracy and state-run corporations.

With a tenuous coalition in hand, during his first years in office, Lula implemented a series of poverty-reduction programs, expanded the number of public universities, and fashioned an independent foreign policy by distancing Brazil somewhat from the United States, among other measures. However, without a stable partisan majority, his political lieutenants only managed to get legislation approved in Congress through a vote-buying scheme, dubbed mensalão, because congressmen and senators received monthly payments in exchange for giving the Workers’ Party-led coalition their political support. After the scandal broke, several of Lula’s closest allies were found guilty and served prison sentences, although the president was not directly implicated.

The affair tarnished the image of the Workers’ Party. Nonetheless, Lula, who is incredibly charismatic and popular among the lower and working-classes, won reelection in 2006. During his second term in office he continued his signature social programs, built strong alliances with major national economic interests, and captured the bids for the 2014 World Cup soccer games and the 2016 Summer Olympics. Export earnings drove the economy and fueled significant domestic economic growth, averaging four percent a year. Lula left office with an 83 percent approval rating, perhaps the highest in Brazilian history. His handpicked successor was Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s former Minister of Mines and Energy and then his Chief of Staff.

Rousseff, who had joined a revolutionary organization in 1965 while still in high school in response to the 1964 military coup d’état, participated in the armed struggle from 1969 until early 1970, when she was arrested and tortured for over a week. Two iconic images of the young militant from that period symbolize her commitment to social change. One is the mug shot of a fuzzy-haired young woman with thick glasses who had just been arrested. In the other, she is sitting erect on a courtroom chair staring into the camera during a session of the Supreme Military Court that had charged her with violating the National Security Act, while her uniformed judges hide their faces to avoid identification. Her detractors use these photos to denounce her radical left-wing background. During the impeachment process, Rousseff and her supporters alluded to these same images as symbols of her courage, fearlessness, and her intransigent commitment to transforming Brazil.

As part of Rousseff’s 2010 electoral strategy, she forged a major alliance with the Party of the Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB), with Michel Temer as her running mate. The PMDB was originally established during the military regime and played a significant role in the legal opposition and in the process of democratization in the 1970s and 1980s. However, since then, it has transformed into a party more interested in remaining in power, and benefitting from access to the state, than in defending a coherent political program. With a left-center coalition that included other political parties, Rousseff continued many of Lula’s social programs, focused much of her efforts on large-scale public construction projects, and oversaw an economy that was slowly collapsing in a delayed response to the 2008 worldwide recession.

In June 2013, popular mobilizations, initially opposing public transportation fare hikes, exploded onto the political scene. The protests represented a complex combination of those demanding that the government expand and improve social service, health, and educational opportunities, and others challenging the on-going rule of Rousseff’s government and the Workers’ Party. Many questioned the administration’s spending priorities of constructing new soccer stadiums for the World Cup when those resources could have been better used to meet the poor and working-classes’ immediate needs. During the initial outbreak of nationwide demonstrations, the mainstream media, which is predominately rightwing, condemned these actions, but as the protests took on an anti-Dilma tone, the media began to support them. Without a clear response to the demonstrators’ demands, Rousseff’s popularity dropped dramatically.

Nonetheless, during the 2014 presidential campaign she managed to eek out a 3.2 percent victory in the second round against the center-right electoral coalition led by Aécio Neves of the PSDB. (Rousseff won with a margin slightly lower than Obama’s victory in 2012 against Mitt Romney). The losers questioned the electoral results, blamed Rousseff’s success on uneducated voters lured into supporting her reelection because of the social programs her government sponsored, and refused to cooperate with the president in passing any Congressional legislation to address the deepening economic slowdown. In a move some observers considered an attempt to reach across the aisles and win backing among her center-right opponents, but which alarmed many of her supporters, Rousseff appointed Joaquim Levy as the Minister of Finance. Levy implemented belt-tightening measures that included drastic budget cuts to government spending. Rousseff also picked Katia Abreu to oversee the Ministry of Agriculture, evoking sharp criticism by those that consider that Abreu, the former president of a national association of landholders, unduly favors agribusiness over small-sized farmers.

At the same time that both left-leaning and conservative-minded protesters mobilized in 2013 and Rousseff prepared for her 2014 re-election bid, Sérgio Moro, a federal judge, and a team of lawyers from the city of Curitiba, Paraná, were carrying out a money-laundering investigation that would influence national politics. In an operation known as Car Wash (Lava Jato), Moro used a form of plea-bargaining to extract testimony of those detained and charged with crimes in exchange for their impunity. Moro’s investigations began to unravel a complex web of billion-dollar kickback schemes that involved high-level executives in Petrobras, the state-owned oil corporation, as well as private company executives who had obtained government contracts. The steady leaking of information about the investigations implicated political appointees of the Lula-Rousseff administration, as well as many politicians of her Congressional coalition, including Eduardo Cunha, a member of the PMDB and the President of the Chamber of Deputies, and Renan Calheiros, President of the Senate and also a leader of the PMDB. Subsequent “confessions” also pointed the finger at center-right politicians who had opposed Rousseff in the 2014 elections.

The on-going drip of leaked news from the Car Wash investigations fueled anti-Rousseff forces that organized large-scale mobilizations throughout 2015 calling for the impeachment of the president. A team of lawyers, financed by the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, drew up a set of accusations that were presented to the Eduardo Cunha in December 2015. However, they stalled in the Chamber of Deputies as Cunha fought off changes of money laundering, taking possibly up to $40 million in bribes, depositing millions in Swiss bank accounts, and being involved in the sacking of Petrobras through fake contracts. When three PT members of the lower chamber’s Ethics Committee refused to support Cunha and stave off charges against him, the President of the Chamber of Deputies, in an act of revenge, pressed forward with the impeachment process against Rousseff. He met with Vice President Michel Temer to coordinate efforts and lined up the necessary two-thirds vote in the lower house with promises of ministries and other benefits after Temer assumed the interim presidency. A taped conversation between politicians involved in corruption dealings later confirmed that Cunha moved against Rousseff to stop his own ouster from the Presidency of the Chamber of Deputies and the loss of his seat in Congress.

On Sunday, April 17, in a Congressional session that shocked much of the nation because of the aggressive and flamboyant ways in which members of Congress declared their vote in favor of ousting the president, a two-thirds majority of the Chamber of Deputies voted to recommend impeachment hearings be held in the Senate. A committee of that body endorsed a report that suspended Rousseff for up to 180 day and passed on executive power to Michel Temer as Interim President. Temer immediately announced a radical turnabout in economic and political policies and appointed a cabinet made up entirely of white males.

These measures provoked mobilizations nationally and internationally, with “Out with Temer” (Fora Temer) as the unifying slogan of the opposition to impeachment. Activists argued that the charges against Rousseff were flimsy at best, and that the new government had adopted new policy directions that reversed the program of the Rousseff electoral coalition. Among international voices that questioned the impeachment process was the Executive Committee of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA), which passed a resolution, later ratified by the membership, criticizing the fact that “the arbitrary and casuistic manner in which the impeachment process is being carried out against President Dilma Rousseff constitutes an attack against Brazilian democracy.”

Though behind the scenes wheeling-and-dealing, Temer managed to pull together a Senate coalition that ultimately removed Rousseff from office. Some have pointed to a statement made by Senator Acir Gurgacz from the state of Rondônia, when he stepped out of the chamber, to explain why he voted for impeachment, as an indication of the political rather than juridical nature of the proceedings: “We were convinced that there was no crime of responsibility in the trial, but there was a lack of governability, and the return of the President at this time could cause greater trouble for the Brazilian economy.” Most Senators favoring her impeachment, however, insisted that although their statements of the floor of the chambers reflected criticisms of Rousseff’s overall governance, their vote relied on evidence of budgetary improprieties.

The presidential impeachment could be the first of a five-point program designed to upturn all of the changes that the Left has achieved over the last two decades. Lula is the next target. Charges of money laundering and corruption have been leveled against him related to an apartment his wife had considered buying. If indicted and found guilty, he would be barred from participating in the 2018 presidential elections, which would allay concerns by the center-right about his potential victory due to his on-going popularity.

A third item that seems to be on the Temer government’s agenda is rolling back all of the social programs developed during the Lula-Rousseff governments, as well as historic labor protection and social security benefits, using the argument that belt-tightening and austerity measures are the only way to fix the economy. An additional goal seems to be the opening of the economy to even greater foreign investment, the privatization of state-owned companies, and the expansion of oil exploration by multinational corporations. Finally, given that fact that approximately 20 percent of Congressional members are evangelical Christians, it is likely that many social advances for LGBT people, women, and people of color, will be curtained under the new administration.

In the week following impeachment, forces against the new Temer government have begun to coalesce in large public demonstration. Municipal elections that will be held in October will test the strength of the different political parties and electoral coalitions, with the Left expected to lose ground. Former President Rousseff has called for immediate direct elections, which seem unlikely, and Lula has proposed the establishment of a broad left-wing electoral front that might launch a presidential candidate in the 2018 race who is not from the PT. Grassroots activists, students, and many youth seem energized to continue opposing the measures of the new government. However, what will happen in the immediate future is really anyone’s guess.

James N. Green is the Carlos Manuel de Céspedes Professor of Latin American History at Brown University and Director of the Brown-Brazil Initiative.

(A prior version of this article said economic growth under Fernando Henrique Cardoso averaged 4.6% annually. We regret the error.)