“[It] boils down to questions of trust--a quality that cannot be legislated, proposed or promised in the abstract so much as demonstrated, earned and granted in negotiated, contingent, concrete relationships in the here and how."

- Bill Nichols in ‘What to do about documentary distortion? Toward a code of ethics'

From 2009 to 2015 I worked as a producer and translator for Salero, a documentary film set in southwestern Bolivia on the world’s largest salt flat, the Salar de Uyuni. The film follows Moises Chambi, a 25-year-old native of the small town of Colchani who begins the film working as his father and grandfather have, gathering and selling salt for human consumption and industrial processes.

When we began filming, the Salar was featured regularly in the news as the world’s largest deposit of lithium — a key raw material in electric car batteries and laptop computers. We first traveled to Bolivia with the intention of filming a shorter piece for television, riding a wave of news mentions that grew daily. South Korean, French, and Canadian film crews raced back and forth across the Salar, competing with each other for hotel rooms and interviews with locals. Our trip to the Salar in August 2009, my first as documentary filmmaker, was exhilarating. It felt like our crew was on the frontlines of the world’s most important and timely story. We had little time to sit back and reflect on how a particular interview had gone, or to take in the vast, eerie expanse of the Salar – it was a whirlwind.

Our second trip to the Salar revealed a much more fraught dynamic. During a long conversation with Moises’ cousin, Neber, the subject turned to the network of open-pit silver, lead and zinc mines on the edge of the Salar that were owned by foreign companies. Neber eventually asked what I was being paid for my work on the film. His brow wrinkled as I tried to explain how our production was “independent,” funded by grants and a non-profit organization, and that I was barely being paid enough to call it a real job or even pay my rent. “How much is that camera of yours worth?” He asked. At the time, the RED camera package we were using retailed for around $15,000 dollars — roughly what Neber earns in a year and a half. “All you people are the same,” he noted, “you’re just like the mining companies. You’ll go back to your country and make money on this film then forget about us.”

At first the comparison struck me as unfair. Couldn’t Neber see the difference between us — a tiny, underfunded film crew — and Sumitomo, the multinational operating the mine on the opposite end of the Salar? As our project developed into a full-length film and we returned to the Salar for a third, fourth, then fifth time, however, I began to see documentary film and television about the Global South in a different light: operating under certain parameters that reinforce the very pattern it claims to help dismantle.

The story I heard often went like this: having done very little research of its own, a film crew flies down to the Salar for two to three days, films a series of interviews and locations the local producer had arranged, then sends the material back to offices in New York, Tokyo, London, or some other city-state for immediate editing and publication. In my experience, such pieces almost always resulted in the same logline: “Poorest country in South America seeks to harness vast, untapped resource.”

Concretely, the rush to produce allows for little, if any, actual interaction between film crews and the subjects they film, and means that the physical and social situation is primarily experienced (and talked about back at the hotel) as an inconvenience. Television and film typically operates on a tight production schedule and limited budget, and the immediate task is often all-absorbing: focus the lens, make sure the interview is going to happen at 2 PM, do we have enough 9-volt batteries, etc. Nevertheless, beyond any technical constraints I came to see the peculiar blindness of the production process not as the cause but the effect of certain assumptions that film crews hold about the individuals and communities they film. This blindness manifests in gestures as small as jokes or body language, and things as large (and invisible) as the presumption that an interviewee has nothing better to do with his or her time than answer the same question again and again for the camera. This is the real one-way street of documentary film: few of the residents I spoke with had seen any of the reports and articles that had come out about the Salar in Western media; most seemed indifferent to the attention.

Bolivia’s long history of resource exploitation casts this attitude in a particularly bitter and ironic light. As the astounding story of the Spanish plundering of Potosí’s Cerro Rico assumed a more important role in the film, I saw Neber’s initial skepticism within the context of Bolivia’s past experience of abuse. Bolivians have seen so many foreigners come and go, each promising their own version of wealth, fame, heaven, or progress and routinely failing to make good on that promise, that it was only reasonable to assume that the most recent batch — film crews — would repeat the pattern.

Western media’s condescension in turn gives the impression that it views its subjects much as foreign mining companies had done previously: a kind of raw material existing for Western consumption. In its modern form, the company is not on the lookout for silver or gold — the crude physical materials of primary extraction — but rather stories, thoughts, feelings. Once it has ‘mined’ its subjects for this material, the company returns home to create a value-added product: well-crafted political films or programs that win prizes in prestigious film festivals and establish reputations. By our last trip, Neber’s resentment didn’t strike me as misanthropic or distrustful so much as logical.

Bolivians I spoke with about this were keenly aware of this dynamic, but what are their options? If a laborer is paid $100 to be a filmmaker’s driver for the day and he gives an interview in the meantime, that’s still a good wage. During film shoots I began to imagine a Bolivian film crew arriving in my hometown of Seekonk, Massachusetts to film a documentary on the controversial new shopping mall. Where would they stay, what would they ask? Who would translate? Would they try to film in my family’s kitchen with a five-person film crew? What if my family were busy, or were afraid of political persecution from the town but felt too shy to refuse? Reflecting on the absurdity of the situation not only underscored documentary filmmaking as a culturally- specific activity— more importantly, it exposed the real power differential at stake in projects like the one I was pursuing.

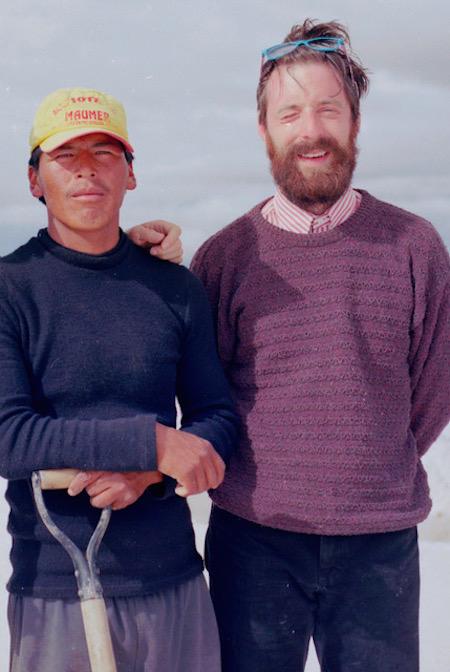

The saving grace in all of this — the first and last reason we were able to film in Colchani — was our relationship with Moises and his family, whose patience, sense of humor, and willingness to spend time with first-time filmmakers from New York made the whole project possible. While we were peers with a similar wry sense of humor, there were real moments of conflict. Sometimes we demanded more than we should have, sometimes he didn’t show up and we would lose hours of daylight. When I consider my part in what allowed our relationship to evolve beyond one of mutual convenience, and I learned these all the hard way, I realize it was crucial not to make cavalier promises, to stay in touch between film shoots with calls or notes, and to trust Moises implicitly as an expert in his own reality. For all of our bright ideas about visual metaphor, Moises’ ideas for filming were often much more concrete and fruitful. After years of trying to film Bolivian president Evo Morales on the Salar, Moises called us one morning at 5 AM with a tip from his brother that Morales, who is notorious for scheduling last-minute appearances, would be giving a speech at 11 that morning, a moment that came to play a crucial dramatic role in the film.

A documentary is always the expression of a relationship. The tone of the television programs I mentioned above, for example, is explained as much by the distance they held from their subjects as by any political or intellectual bent. The greater share of the burden in building and maintaining these relationships falls to filmmakers, not least because it is often filmmakers who initiate contact. In the long run, it is also due to the documentarian’s active role in the “constant negotiation between an event and its representation,” as Linda Farthing and Benjamin Kohl have written. It is easy to forget that documentary films are rarely the innocent, spontaneous creatures that audiences take them to be. To give the simplest example, we fit six years of filming and audio interviews — hundreds of hours of footage — into 80 minutes. Documentaries are highly constructed, contingent arguments, and in the vast gulf that divides lived reality from the story presented, what filmmakers ‘know’ or reveal about their subjects reveals a great deal about themselves as artists and, more broadly, as humans. When I watch Salero now, I can see our film crew staring back, the sum total of our decisions, foibles, and minor victories reflected through a glass.

What is the ethical responsibility of documentary filmmakers towards their subjects? What is the correct response when a village leader asks the film crew to pay for new street lights, as was asked of us? What if your central character calls one day to tell you that his son burned his hand badly on the stove and the family has no money to pay the medical bills? I am certain that all documentarians wrestle with these questions, and there is no final court of appeal. My short time in filmmaking has taught me that ethics is a matter of degrees, about concrete action in the here and now. In our case, we did not end up giving money for the street lights, and instead bought soccer jerseys and notebooks for the elementary school; we helped to pay for the medical bills out of our own pockets.

After finishing the film, we organized a screening tour throughout Bolivia. Beyond reconnecting with old friends, we hoped for our film to provide a different perspective on the lithium project. We showed the film in several larger cities, but also ventured into the countryside with a projector to show it in small community centers, local universities, and, at Moises’ insistence, a dance hall in Colchani.

The hall was hot, small, and crowded with 150 schoolchildren that afternoon. As the children ran around, several older townspeople moved around in the back, squinting at the screen we had jerry-rigged and chuckling mysteriously throughout the film. While I was happy to be back in Colchani, I mostly felt awkward, like a gangly teenager showing off his dance moves at a junior high school talent show. What would they think? What would they think about what we thought? What did I think about what I thought? The silence at the end was unnerving because I didn’t know how to interpret it— I wasn’t sure whether the film had triggered negative feelings towards the lithium operation or us, or whether the audience was simply taking its time, absorbing a foreign take on their lived reality. At some point during the film I remember looking up to see Moises, standing there with his two sons, watching our version of his story on the big screen with tears in his eyes. I cried, too.

The Salar changed visibly over the six years that we filmed. By the time I returned, in the spring of 2017, a highway connecting La Paz to the Argentinian border bounded its edge, a new airport brought in thousands of tourists during the high season, and an expanding complex of government facilities filled a landscape that was previously home only to small, dusty towns, stoic troops of llamas, and the wind of the altiplano.

Moises has long since given up gathering salt. Today he drives tourists around, works in hotel construction and sometimes works as a fixer for television and film crews that come to film in the area. One of the first questions Moises asked me when we sat down to eat was about the airplane I had taken — “What is it like to fly and look down to see the ocean?” As we spoke I realized that my mode of arrival— the very possibility of seeing Moises again— was what separated us in the first place. I came from a world where a flight to Bolivia was a regular part of the conversation, Moises came from a world where that was effectively impossible.

I will never resolve the great differences between the wealth and power of my country relative to Moises’, but I also don’t believe that wealth — individual or societal — is all you can say about a person. In my heart of hearts, I still believe that in filmmaking or journalism at large, an honest effort to care for one’s relationships can, as Kohl and Farthing argue, “lessen the tension between the first world self and the third world other — not to deny difference, but to understand the distance as a lesson in the possibility of coalition politics”. While the difference and distance between documentarian and subject — expressed most bluntly in who stands behind the camera — is real, so is my friendship with Moises, as is the fact that neither of us are the same for the days we have spent together under the sun.

Noah Harley is a translator and filmmaker based out of New York; Salero is his first film. He is currently working on a documentary about Mariela Castro, a leading LGBT advocate in Cuba and the daughter of president Raul Castro.