This article is part of a special roundtable forum on the Lula conviction. Click here to read the rest!

“O, he sits high in all the people's hearts:

And that which would appear offence in us,

His countenance, like richest alchemy,

Will change to virtue and to worthiness (...)

Therefore think him as a serpent's egg

Which, hatch'd, would, as his kind, grow mischievous,

And kill him in the shell.”

--The Life and Death of Julius Caesar, William Shakespeare

Like the Shakespearean assassins of Julius Caesar, the prosecutors and judges who condemned Lula consider themselves guardians of republican virtues supposedly under threat by an unscrupulous power project based on the manipulation of the masses. The prosecutor at Lula’s trial on January 24 attacked what he called a “shock troop” mobilized in favor of the defendant, especially from the academic world. In his view, by associating the persecution of the former president with the destruction of the country’s social advances over the last decade, his supporters promote a type of “Sebastianism,”* with dire consequences for the country.

Much like the military coup mongers of 1964 in their self-proclaimed duties to cleanse national institutions, members of the police-judiciary apparatus—operating in conjunction with the mainstream media—triggered a shift in meaning of the very concept of corruption, the supposed target of their actions.

The charges against Lula clearly illustrate such semantic transformations. Traditionally, a politician who uses their power for personal enrichment is classified as corrupt. Now, as Operation Car Wash itself has shown, second-tier Petrobras managers have accumulated hundreds of millions of dollars in assets. So it would make no sense to believe that the alleged supreme leader of the state oil giant’s resource misuse scheme would be rewarded with the renovation of a middle-class apartment and a second-rate ranch, neither of which were registered in his name. In fact, if Lula’s engagement in public life was motivated by illegal self-enrichment, he could have accumulated wealth far beyond his current status since his time as the head of the Metalworkers’ Union of São Bernardo do Campo and Diadema in the mid-1970s.

In fact, what Car Wash demonstrated to the point of exhaustion was the existence of an immense system of illegal financing in which part of the extraordinary profit obtained by a cartel of large contractors was distributed to politicians from every party with significant influence in the executive and legislative branches. This explains the donations in the millions of reais made in the parallel accounting of companies to politicians of the opposition party, the PSDB, who, meanwhile, have been spared arrests and the loss of parliamentary mandates. The investigation of the denunciations, in these cases, follows the usual pattern of impunity for Brazilian elites.

But the “corruption” that condemned the ex-laborer is other. As the politicians of the former National Democratic Union, the party based on the urban middle class whose raison d’être was the relentless fight against President Getúlio Vargas and his legacy, would say: “the greatest corruption is to buy the people’s support” with social benefits. In this elitist conception of politics, if the political process generates support for leaders who improve the lives of subordinate sectors, its legitimacy becomes suspicious, and “purging” measures become necessary. In the name of democracy, they resort to a coup.

The sentencing of the former president to 12 years in prison is the latest landmark in the evolution of the major political operation underway in Brazil since 2013. The objectives of the new power bloc in the country have always been clear: overthrow President Dilma Rousseff, since it was impossible to defeat her at the polls; reverse the process of reducing material and symbolic inequality initiated in 2003; repeal the social rights established by Vargas-era labor legislation and those established by the 1988 Constitution; annihilate aspirations for national development and any leading role by Brazil on the international scene; destroy Lula politically and prevent him from being elected to the presidency; criminalize, and if possible, banish the Workers’ Party.

Although initially the coup leaders under President Michel Temer advanced without major roadblocks, the resistance of the left and social movements, particularly over the last year, has been successful in mitigating or at least delaying the full implementation of the reactionary program described above.

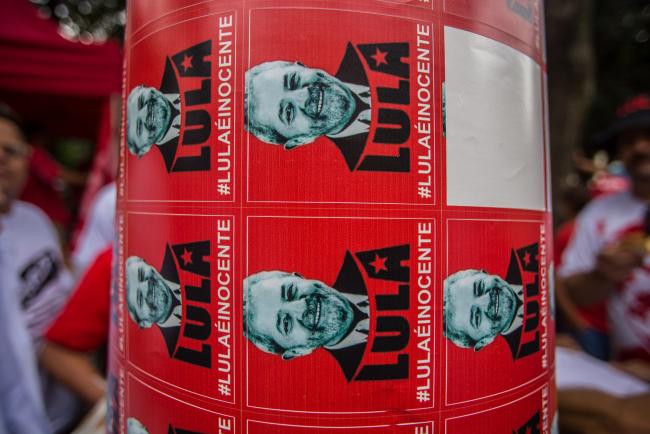

With regard to Lula, the outcome is dubious. The process of demonizing his image was conducted gradually so that the moment of his condemnation would coincide with his total isolation and demoralization. In the euphoric moments of the movement to impeach Dilma, the Brazilian right dreamed of a day when the ex-president’s condemnation would be celebrated by crowds on the streets. But on January 24, the pots normally banged were silenced, and the mobilization in solidarity with the defendant largely outnumbered the number of opponents who took to the streets to celebrate.

On one hand, the conviction was obtained based on evidence that, as Mark Weisbrot wrote in the New York Times, is “far below the standards that would be taken seriously in, for example, the United States’ judicial system.” This, initially, makes it unlikely that he could return to win and exercise the presidency, and generates the real risk of his imprisonment.

On the other, the popular reception of this condemnation is far from what was imagined by his enemies a year or two ago. Obviously, Lula will never again reach the 90% approval rating recorded at the end of his second presidential term. But at the moment, he would lead in the polls by a wide margin, generating fears about the consequences of a possible cancellation of his candidacy.

Several factors may explain this resurgence in favor by about half the population of this continental country for its former president. The judiciary’s partisanship became self-evident. The aggressiveness of the new right gestated in the impeachment process unnerves moderate voters. Several of the pre-candidates on the center right are demoralized by corruption allegations, as well as their involvement in the unpopular, coup-led Temer administration. There is a stark contrast between these fragile hopefuls and a leader who, within a few months of touring the country, has regained a significant portion of his support base, and has again mobilized it in defense of the rights gained during his administration.

Brazil's progressive forces face the enormous challenge of building a new political alternative for the country, which requires the ability to balance the PT’s mistakes and successes. But the game is far from over—and Lula will continue to play a key role in it.

Alexandre Fortes is a professor at the Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro.

Translated by Emma Young.

*A reference to the popular millenarian belief that the Portuguese king Dom Sebastião, killed in the battle of Alcácer-Quibir in 1578, would return to establish a kingdom of justice and abundance.