This article was originally published in Dissent.

Cubans are angry. Communist Party militants rail at the secretiveness surrounding the selection of Raúl Castro’s successor. A middling Party official in Pinar del Rio complains angrily, over a boozy lunch with friends to which I am invited, that the Party hierarchy hasn’t taken leading members’ views into account in the succession process. “It always used to take soundings. I hear they have consulted at higher levels, but nothing here. We feel abandoned.” She says, pointing to me, “She knows as much I do about the traspaso [presidential transfer]. And there’s another problem. People haven’t warmed to Miguel Díaz-Canel (Castro’s presumed successor). He is cold, distant, he never smiles. He has done little to distinguish himself.” I am astonished she is so forthcoming, so reckless.

I am with a Cuban friend who is doing field work in Pinar del Rio, Cuba’s westernmost province. Many people, Party militants included, tell her the local government isn’t functioning, and they feel abandoned by Havana. My friend asks what they are doing about it. They shrug.

A close friend in Havana, a well-respected writer, is uncharacteristically blunt. “Cuban socialism, our international reputation for upholding human dignity, has ended in this strange quasi-capitalism.” Younger Cubans and those outside official circles tend to be indifferent. Mario, a young but relatively high-level state functionary and somewhat reluctant Party militant, who lives in the poor outer-Havana borough of La Lisa, says his friends are apolitical. “They don’t think the transfer will make any difference. Raúl will remain head of the Party. Their lives will be just as difficult they are today. Nothing will change.”

Ofelia, from Alamar, a Soviet-era housing project east of Havana, sells second-hand clothing donated by the Evangelical Pentecostal Church she belongs to, an offshoot of a California congregation. “It doesn’t matter who is president. The big people will get richer, the people at the bottom, people like me, will remain poor.” She tilts her head and smiles faintly, “We no longer have Fidel on our side.”

When I ask my chum Yudith, a lifelong Party loyalist, how she sees the current situation, she replies, “Let’s not discuss politics. It’s too grim. Let’s talk about pleasant things.”

During three weeks in January 2018, I talk with a dozen long-time friends in and around Havana. I record interviews with Cuban men and women I have been interviewing for fifteen years. I encounter anger, frustration, a newfound outspokenness, and resignation. Almost everyone I meet is gloomy. The mood is contagious.

I participate in a workshop at a leading research institute. Most people in the room criticize the government’s pro-market economic policies. Many of them are studying the effects of inequality. To counter their criticism, a few participants declare that Raúl Castro is doing what needs to be done, and they are confident the government will remain in safe hands. One speaker from the floor weaves extravagant praise for the Communist Party of China into a long tribute to Cuba’s leadership. The audience waits patiently for him to finish, many looking skeptical. Closing the session, the chair furiously bangs her notebook. “Decision-makers pay us no attention. Marxism has been thrown out the window in this country.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Cuba entered a long economic crisis from which it has not effectively recovered. To keep the economy afloat, to keep the lights on, to import basic foods and medicines, Fidel and his advisors encouraged tourism. The state legalized circulation of the U.S. dollar, and permitted Cubans to open tiny businesses, renting rooms, running at-home restaurants largely catering to the tourist trade. But begrudgingly. Fidel repeatedly threatened to outlaw the businesses once the economy recovered. He waged the last great ideological struggle of his lifetime, the Battle of Ideas, against the rise of the new entrepreneurs—who Cubans call the new rich. Most Cubans resented rising inequality in the beginning. Many told me it betrayed the ideals of the Revolution.

When Raúl Castro succeeded his brother, official policy substantially shifted. Raúl Castro’s government shelved the Battle of Ideas, set in motion large-scale layoffs in the state sector, and encouraged the expansion, within limits, of private businesses. A small number of Cubans were able to take advantage of the more favorable atmosphere to push the boundaries of what was possible, legally and illegally. With money from relatives in Miami, or embezzled from the state, the new rich opened large, garish restaurants, bought properties to operate upscale Airbnbs, ran small and not-so-small import operations. Many flaunted their newfound affluence.

Raúl Castro portrays the new entrepreneurs as offering hope for Cuba’s economic future, so long as they abide by the rules of the game. The newspaper Granma, which represents the official version of the Party line, explains it is necessary to tolerate expanding disparities in income and wealth, up to a limit, as private entrepreneurs bring in the foreign exchange that pays for Cubans’ universal health care and free education. Gradually people’s anger at what they perceived as a betrayal of the Revolution turned to accepting the inevitability of economic inequalities. Instead of, or alongside, complaining, they try to insert themselves into the emerging market economy as casual labor, or, if they have the means, initiating a tiny business as street peddler or “bicitaxi” driver, repairing cell phones, selling coffee outside workplaces.

Although Cubans across the board tell me they are disaffected, it is very unlikely they will act collectively, much less take to the streets. Cubans’ traditional form of resistance is to leave. Now leaving is more difficult than it was before President Obama ended the immigration program designed to lure Cubans to the United States, and before President Trump dramatically downsized the U.S. Embassy in Havana. Nevertheless, Cubans continue to plot ways to emigrate. For decades, leaving has been the escape valve that prevented Cuba’s pressure cooker from exploding.

In early 2018, the atmosphere in Cuba is markedly different from when President Barack Obama visited Havana in March 2016. Then most people I spoke with said that conditions were bad, but they were hopeful. Tired of austerity, tired of scrounging to put food on the table, tired of promises that conditions would improve, they saw Obama as a savior. His photograph hung in windows, on living room walls, even in state-run bodegas. Yudith joked that if Obama ran for president of Cuba he would win by a landslide. Cubans hoped U.S. investment would flow in, tourism boom, private businesses flourish, and the quality of life improve.

If Obama’s plan was to kill off the Revolution with business, Trump has revived the primitive approach to regime change long advocated in Washington and in Miami. He is trying to drive out the government, and strangle the economy, by destroying the Cuban army’s business operations. The Cuban army controls much of the country’s hard-currency economy, including a large part of the tourist sector, the new Port and Free Trade Zone at Mariel, and the major import-export companies and financial institutions. Trump’s anti-Cuba policy is proving surprisingly effective. After Trump announced the measures, the number of U.S. tourists visiting Cuba fell by about a quarter, according to hotel managers. Several U.S. airlines cut back flights to the island. A number of U.S. businesses in the process of negotiating deals with the Cuban government pulled back. In January I saw the consequences of tightening the blockade. Hotels and restaurants in Havana and at the beaches were half-full at best. Tourist buses stood idle in huge parking lots. Several taxi drivers told me they were laid off from jobs in the tourist sector. Russian and Chinese tours are on the rise, but not enough to make up for the drop in tourists from the United States.

Cubans’ misfortunes have been multiplied by Trump, but their sources are more complex. Venezuela, mired in a political and economic crisis, reduced subsidized petroleum exports to Cuba by 40 percent in the past four years. The Port of Mariel, designed to be the hub of Cuba’s new economy, was financed by firms allied to Brazilian politicians who were ousted in a right-wing coup. As Cuba’s government was rebuilding hospitals, schools, and homes ravaged in 2016 by Hurricane Matthew, the island was hit by the even more destructive Hurricane Irma, which claimed lives in and around Havana, wiped out the sugar and cacao harvests, and hit the production of food crops and eggs. In the face of shortages, the government reduced the quantity of food distributed on the ration. Meanwhile, prices on the open market climb.

Cuban society seems to be falling apart. Many, probably most, families supplement their paltry incomes by “diverting state resources”—that is, stealing from the state. “Corruption permeates the entire social order,” Mario, the Party militant tells me. “It has become embedded in our veins. I will give you some examples: a Party member in charge of a hospital cafeteria, a friend of mine, takes food home every day so her family can eat decently. Doctors steal medicine to sell on the black market. A kitchen assistant at the Hotel Nacional, he lives in my building, carries off prosciutto and Manchego cheese, which he sells to rich customers and private restaurants. Everyone steals, most people have to. Of course the higher you are, the more you can embezzle.”

Cubans call the new class of property owners la clase emergente [the emerging class]. They own boutique hotels, restaurants, gyms, repair shops, construction companies, and they cream off state resources on a grand scale. In July 2017, the government put a brake on the growth of the private sector, placing new limits on existing businesses, and halting, for the time being, applications for commercial licenses. No one knows whether this represents a momentary hiatus in the development of the private sector, or a change in policy.

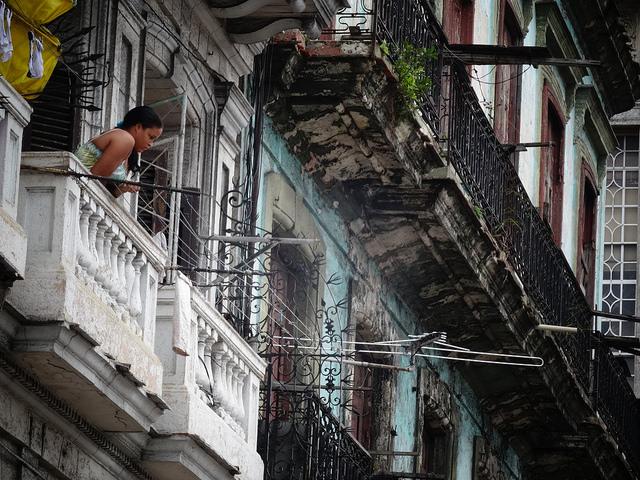

There is another emerging class in Cuba, the jobless and the underemployed. Reliable economic statistics are hard to come by, but reports suggest that in 2017, 20 percent of the population lived in poverty. I watch the poorest Cubans from the balcony of the casa particular (bed and breakfast) where I am staying in Vedado, an upscale Havana neighborhood. They are picking through garbage bins at the corner. I see them begging in Centro Havana. These are not chirpy young men and women trying to charm tourists out of a couple of CUCs, Cuba’s convertible currency, but destitute people sitting on the sidewalk with hand-lettered signs in Spanish asking passers-by for food or money. On Calle Obispo, Havana’s crowded commercial strip, I see a disheveled elderly man pushing a cart with plastic bags, cartons, and rags. A friend and I are on our way to a bookshop. She confirms my suspicion; he is homeless. Homelessness is rare, but the scene might foreshadow what the new Cuba will look like. The book I want to buy is Leonardo Padura’s El hombre que amaba a los perros [The Man Who Loved Dogs], about the man who murdered Leon Trotsky and then lived out his life in Cuba. It costs 30 CUC: a month’s salary in the state sector. Books have become a measure of inequality.

Unidad Nacional

Sonia is driving me to the José Martí airport for my flight to London. She is a good friend who is forever trying to instruct me in the Communist Party line. Her task has been made more difficult because the rumor mill is flooded with stories about Party divisions. As she edges carefully into the chaotic roundabout at the Latin American Stadium, I see a large billboard looming over the road. It announces the upcoming session of the National Assembly, on April 19, where Cubans anticipate that Raúl Castro’s successor will be named. Two words stand out in red script: UNIDAD NACIONAL [national unity]. It is not a declaration, but an exhortation. Raúl Castro needs a degree of political unity to make the succession work. He postponed the transfer for two months, saying the government needed more time to recover from the destruction caused by Hurricane Irma. Cubans who pay attention to politics—and a great many don’t—believe he postponed the transfer because his forces had not yet hammered out an agreement with their adversaries in the Party.

This sounds plausible. Divisions in the Party between Raulistas and Fidelistas run deep. They first burst on the scene in 2009 when Raúl, after formally succeeding his brother, removed Fidel’s closest allies from their positions. After Raúl consolidated his power, he began to open avenues for private businesses, which some Party members believed would undermine socialism. Tensions between the two camps came to a head in 2011 when the Congress of the Cuban Communist Party deleted egalitarianism from the Party’s statement of principles, replacing it with “equal rights and opportunities.” Critics of the change argue that equal opportunities is not a softer version of egalitarianism. It is a method of structuring inequality.

The split between Raulistas and Fidelistas is not the only division on the Cuban landscape. One characteristic of the last decade, the era of Raúl, is that more political voices are tacitly tolerated, if largely ignored. They include los nuevos ricos, Cuban-Americans, Cuban academics, musicians and artists on the island and in the diaspora; anti-racist, feminist and environmental groups; bloggers; and the many Cubans who complain more openly than before. But toleration goes only so far. Pro-democracy groups, musicians, and artists whose music and art clearly opposes the government are not permitted a voice.

On the surface, Cuban politics seems to have come to a halt. Cubans say that beneath the veneer, Raulistas and Fidelistas are fighting it out. Fighting to control the future. The evening prior to my departure I ask Sonia what she expects will happen between now and April 19, the day Castro’s successor will be announced. The date was not chosen arbitrarily: April 19 is the anniversary of the defeat of the U.S. invasion at the Bay of Pigs. Sonia tries to encapsulate this moment in Cuban history. “I am not worried,” she says, though her nervous smile betrays the opposite. “Raúl has the Army and the security apparatus guaranteed. His son is at the top of state security. His son-in-law runs the Army’s business operations. Nothing to worry about there. The Party, well, that’s not so clear. Miguel Díaz-Canel came up through the Party. He’s a Party man. But he will need the Army and the security apparatus behind him. Díaz-Canel can’t say anything right now. He has to keep his mouth shut. Maybe, gradually, after he becomes president, we will find out what he thinks, where he stands. Or maybe we won’t.”

Unlike my friends who grew up with the Revolution, most Cubans I interview honestly do not care what Miguel Díaz-Canel thinks, or what he stands for. They feel profoundly disconnected from the political elite. When I ask about Miguel Díaz-Canel, often the response is, “Who?” or, “Politicians are all the same; they are in it for themselves.”

In most Cuban homes the TV is on all the time. Except when soap operas and football (soccer) matches are on, it is rarely tuned to Cuban channels. Most Cubans watch Univision, broadcast out of Miami, if they can.

Elizabeth Dore is author of Cuba Is Not Like What You Think (Verso Books, forthcoming) and presenter of the BBC World Service radio program Cubans’ Lives.