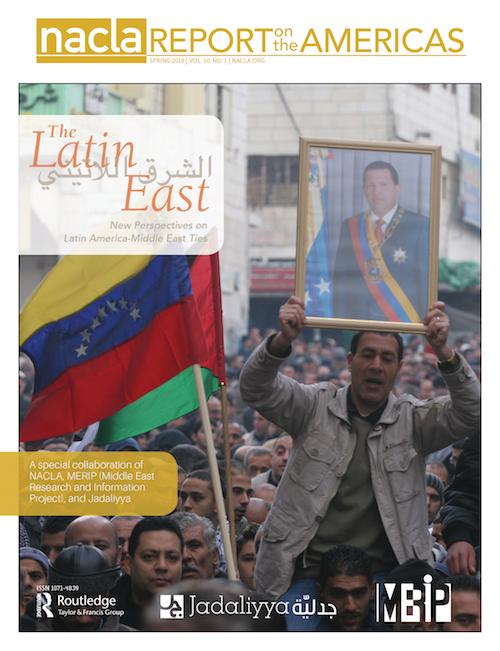

At first glance the scene on our cover is unsurprising: January 2009, thousands packed into crowded streets holding signs in support of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. Since taking office ten years prior, Venezuela’s firebrand president led an unprecedented political transformation that saw one country after another in Latin America elect left-wing governments of various stripes, each linked by a new focus on social spending, wealth redistribution, and state power following decades of neoliberal rule. In the process, Chávez earned the ire of venerable political and economic elites, and the admiration of long-sidelined popular sectors, who came to see Chávez as a champion for the poor and disenfranchised. But what makes this scene remarkable is that it took place not in Caracas, but half a world away in Ramallah, in the heart of the West Bank.

This is a watershed issue of the Report, for several reasons. Not only does it mark the first issue of NACLA’s 50th year of publication—an extraordinary story of struggle, resilience, solidarity, and compromiso to which we will devote our fall number. It also finds us reaching well beyond the borders of Latin America in search of the region’s wider, global, and reciprocal influences. To do so, we have partnered with MERIP (Middle East Research and Information Project) and Jadaliyya in an unprecedented cross-regional and cross-platform collaboration. Much like NACLA, MERIP’s print magazine has offered independent reporting and analysis of the Middle East for nearly 50 years, bringing together prominent academics, scholars, journalists, artists, and activists to cut through the imperial gaze the region has long been subjected to by mainstream media and U.S. policy circles. Jadaliyya, for its part, has quickly emerged as a leading online outlet for crucial and often underreported facets of Middle East politics, society, and culture since its launch in 2011. Together, we have pooled our resources, expertise, and experience to explore links both new and longstanding between parts of the world infrequently considered side by side.

And there is much to explore. Support for Chávez in Ramallah in part reflected the late President’s full throated endorsment of Palestinian statehood, expressed as early as 2006 in fiery speeches denouncing Israeli occupation, delegations of Palestinian activists, students, and politicians in Venezuela, and economic aid sent to Gaza and the West Bank. Chávez also severed diplomatic ties with Israel following a three-week military offensive in Gaza in 2009, and opened a diplomatic mission in Ramallah in 2012. “He really felt the suffering of the Palestinians,” said Hani al-Agha, a 31-year old resident of Gaza, to AFP after Chávez’s death in 2013. Nabil Shaath, an official in Ramallah, observed how Chávez “endlessly worked … for all oppressed peoples, including Palestine.” But what underlay this outreach, and what larger processes, problems, and possibilities did it reveal about ties between Latin America and the Middle East?

In fact, Chávez’s rhetorical and material solidarity toward Palestinians formed part of a much broader, often fraught relationship forged between the two regions at a time of deep flux for both. As the Pink Tide reached its crest in the mid-2000s, left-wing governments throughout Latin America increasingly made generating a “multi-polar world” a central part of a larger agenda to disrupt U.S. hegemony globally. Outreach to Arab nations in particular figured prominently in these efforts. Chávez had led the way as early as 2000, hosting Organization of Oil Producing Countries (OPEC) heads of state in Caracas in 2000 in a bid to file the long-dormant organization’s teeth, meeting with longtime U.S. nemesis Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and later staging massive rallies in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Iran, and elsewhere in the region where crowds, showcasing rifts and dissatisfaction with local leaders, proclaimed him “Chávez of Arabia.”

To read the rest of this article and content from this issue, click here.