On September 5, 2017, Hurricane Irma made landfall, ravaging the islands of Barbuda, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Anguilla, and the Virgin Islands, leaving at least 134 casualties. The hurricane hit Barbuda the hardest, damaging nearly all of its infrastructure and instantly rendering its 1,700 residents climate refugees. From the continental United States, millions watched with bated breath as weather projections showed the hurricane hitting Puerto Rico squarely in its center next. The timing could not have been worse: Puerto Rico is in the midst of one of the worst recessions in its history, under the thumb of an undemocratically installed financial control board, called “la Junta” by locals, and struggling against austerity and the ongoing legacy of colonization and limited self-governance. While many Puerto Ricans in the archipelago and the diaspora breathed a sigh of relief after Irma’s passage, others experienced the storm as an utterly devastating event.

Then Maria came, and Puerto Rico screeched to a terrifying halt. The storm immediately knocked out its fragile power grid. Diesel generators struggled to keep life-support devices running in hospitals, and telecommunication systems faded to black. Many communities in the rural interior and island municipalities were cut off from rescue and assistance efforts. Both local and federal government recovery efforts have been slow, ineffectual, and half-hearted—reminding Puerto Ricans at every turn of their colonial citizenship, and other Caribbean nations of the ways they are constantly ignored and dismissed by the Global North as anything beyond tourist destinations. In response to Puerto Rico’s calls for aid, the federal administration has framed it as unworthy of U.S. assistance, holding Puerto Rico’s economy hostage to its own remedy to the recession—from the privatization of its electric grid to opening up the economy to predatory investors and transnational wealth—which will only exacerbate the endemic problems the nation faces.

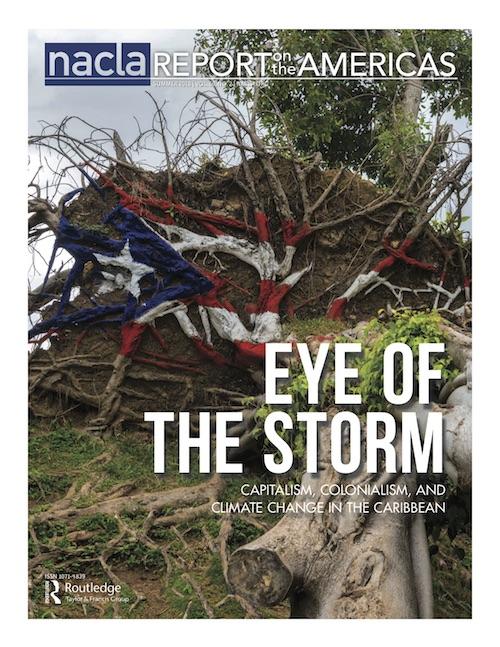

As we approach the 2018 hurricane season, what lessons can we glean from the impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the Caribbean? What can both affected communities and their allies do to prepare for future climate events and prevent the kind of destruction the hurricanes wrought on the region? This issue of the NACLA Report attempts to disentangle some of the conditions that have led the Caribbean to where it is today, as well as how to create a safer and more just future for the region as a whole. The threats posed by climate change loom large as extreme weather events become more intense and frequent, with destructive effects in the region. Yet the articles herein remind us that these latest climate events are a function of manmade disasters. It is impossible to ignore the ways in which neoliberal capitalism, colonialism, and climate change come together in the Caribbean to reanimate and strengthen economic and racial hierarchies that have long marked the region and its place in the world. This issue explores the contours of these historical conditions in its differing iterations in the contemporary moment, from Barbuda to Puerto Rico to Colombia’s Caribbean coast and beyond.

The essays in this issue interrogate the myths and realities of colonial and capitalist development in the Caribbean over the course of the 20th century and into the present. In particular, using Puerto Rico as a telling case study, a number of authors point to the ways that development in the Caribbean has exacerbated the impacts of climate-related disasters. In her essay on infrastructural modernization efforts in Puerto Rico during the early and mid-20th century, Zaire Dinzey-Flores details the flawed foundation of U.S.-led development, particularly during the New Deal and Cold War eras. As Hilda Lloréns’ essay powerfully captures, Puerto Rico’s crisis is not new, and its effects have long reverberated for its most vulnerable residents. Recurrent crises such as the imposition of a federal control board to oversee Puerto Rico’s finances, the fracturing of Puerto Rican communities through displacement and forced migration, or the physical and psychic damage inflicted by Hurricane Maria, according to Lloréns, provide powerful windows into the often invisible forms of precariousness that Puerto Ricans are forced to endure.

To read the rest of this article and content from this issue, click here.