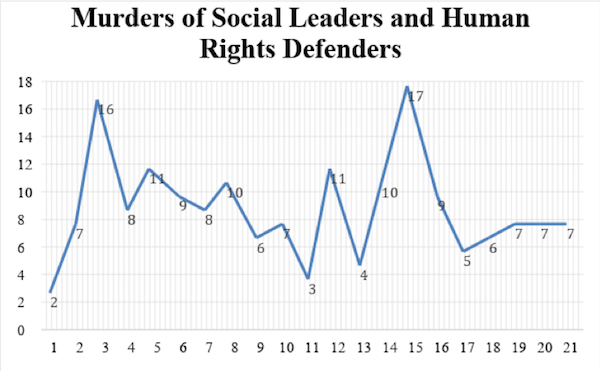

As Congress swore in former President Álvaro Uribe’s protégé and newly elected President, Iván Duque, earlier this week, thousands took to the streets, heeding the opposition’s call for a national protest against a deepening crisis of activist killings across the country. Though anti-activist violence has intensified since the signing of the peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country has witnessed an alarming rash of assassinations of social leaders and human rights advocates in recent weeks. In the first week of July 2018 alone, a whopping total of seven leaders were murdered—a death toll of one per day. Center-left and leftist parties, human rights organizations, and the United Nations condemned the violence, while throngs of people poured out into main squares for a nationwide candlelight vigil.

Recent presidential candidate and now opposition leader Gustavo Petro has been among the chorus of voices decrying the spike in anti-activist violence. During that first week of July, he called on then President-elect Duque to do the same, pointing out that several of the victims had campaigned for Petro in the last election cycle. Several rightwing and centrist politicians and publications subsequently pounced on the opportunity to paint Petro as a hypocritical hack who was attempting to milk the murders for political gain. La Silla Vacía accused him of spinning a “narrative” that played up his campaign’s connection to the victims and blamed uribismo’s return to power for triggering the violence. Fernando Londoño and María Fernanda Cabal, both prominent members of Uribe’s Centro Democrático (Democratic Center) party, soon echoed this charge. In Londoño’s own words, “No hay muerto que no sea partidario suyo”—roughly, “All of the victims somehow supported his candidacy.” But who’s really playing politics here?

A Rise in Targeted Violence

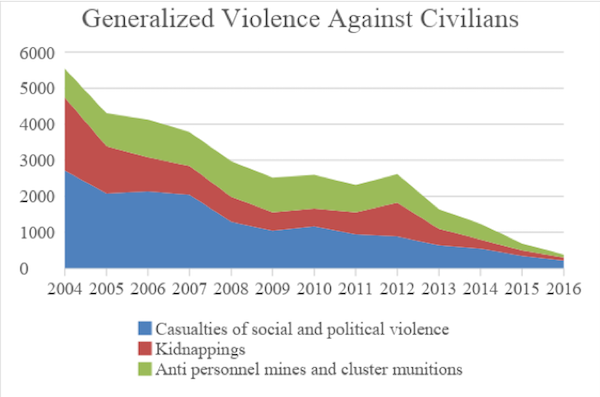

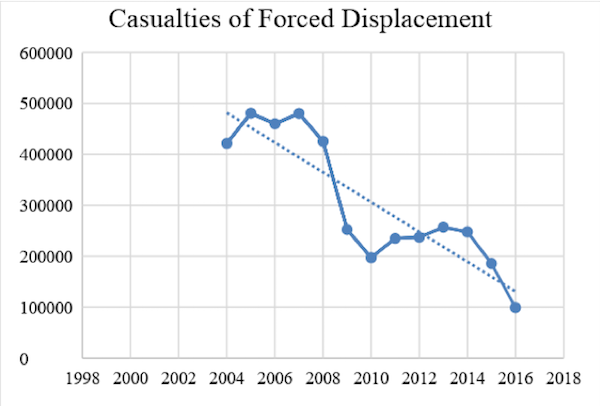

Since the signing of Colombia’s peace agreement on November 24, 2016, Colombia has experienced a decline in generalized violence but an uptick in targeted violence. Though generalized violence had risen sharply in the period between 2004-2008, it fell between 2012-2016, mirroring the time period of the negotiations. The peace process and subsequent accord with the FARC led to a partial abatement of the use of political violence in Colombia, producing substantial decreases in conflict-related homicides, including those due to anti-personnel mines and cluster munitions; casualties due to forced displacement; and kidnappings.

At the same time, in some parts of the country, such benefits of the accords have yet to materialize. The FARC’s withdrawal from the areas where it once exerted considerable political, economic, and social control has created a power vacuum that other armed actors vying for control over land and illegal rents have rushed to fill. Given its historic neglect of these areas and its limited capacity, the state has struggled to keep apace with their advance. These armed actors include the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), the self-proclaimed Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Gaitanistas or AGC, the country’s largest and most powerful paramilitary successor group), and the newly formed FARC dissident factions, all of which undermine the implementation of the peace deal.

Targeted violence is of course not a new phenomenon in Colombia. In the 1940s and 1950s, a wave of violence wracked the Colombian countryside. During this period, referred to as “La Violencia,” armed bands of Liberals and Conservatives, the country’s two leading parties, took up arms in a power dispute that cost 200,000 lives and displaced over two million. Only a few decades later, in the 1980s, a political genocide followed a failed peace process between the FARC and the government of President Belisario Betancur. Key members of Colombia’s traditional political class, paramilitaries, and other state agents conspired to wipe out the Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union), a newly founded leftist political party. The extermination began in 1984 and left over 5,000 activists murdered, crushing an entire political movement with complete impunity. This state-sponsored massacre was one of the worst bloodbaths in Colombian political history.

Now, within these new arenas of conflict, a systematic pattern of targeted violence against social leaders and human rights advocates has been developing. According to the Fundación Paz & Reconciliación (Peace and Reconciliation Foundation, PARES), an activist is murdered every four days, demonstrating the state’s continued inability to protect at-risk activists. That makes for a total of 170 murdered leaders since November 24, 2016, including 27 women and, according to Colombia Diversa’s database, seven with diverse sexual orientations and/or gender identities. In the vast majority of these cases (143), the person or persons responsible for “putting out the hit” remain unknown, suggesting that legal actors may be hiring criminal enterprises to do their dirty work. In the remaining homicides, the alleged principal perpetrators have been identified as the Gaitanistas (12), the ELN (6), security forces (5), and FARC dissidents (3).

The three major spikes in anti-activist violence associated with the recent peace process imply political motivations. The first occurred leading up to the October 2016 plebiscite that sought to ratify a previous version of the peace deal, an early sign of the dangers inherent in promoting it. As new leaders cropped up to defend the accords, violence against them proliferated. The second and third spikes occurred following the recent legislative elections in March and the presidential elections in June, which suggests that the Right’s sweeping electoral victories have emboldened legal and illegal actors that have traditionally relied on violence to reach their political objectives.

While victimization patterns vary across the country, the victims are generally victim’s rights activists, including for rights to land restitution, truth, and reparations; peace deal advocates, in particular those seeking to combat illicit economies like drug trafficking and illegal mining; rural and opposition leaders with political aspirations; and defenders of collective rights, in particular those relating to Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities. In other words, though the surge in anti-activist violence may not be the result of a national political project promoted by any one particular paramilitary successor group, it does reflect local political and economic interests. Take the Urabá region in northwestern Antioquia, for example, where most of the social leaders assassinated advocated for land restitution. This makes sense in light of the long-standing clashes over land rights between multinational corporations, business interests, wealthy landowners, victims of the armed conflict, and Afro-Colombian communities.

Despite the recent onslaught of criticism leveled against Petro, cases like the murders of Ana María Cortés in Cáceres, Antioquia, and Luis Barrios in Palmar de Varela, Atlántico, as well as the death threats aimed at Robinson Piedrahíta in Tarazá, Antioquia—all active field organizers for Petro’s campaign—suggest that there could also be a systematic plan in the works to attack Petro’s Colombia Humana political project. Its aim could be to snuff out the movement’s political aspirations as well as those of other opposition parties in regions such as Bajo Cauca, Córdoba, Cauca, and Nariño. Logically, the Colombian Left, including the new FARC party, fears that the Union Patriótica’s history could be repeating itself.

Depoliticizing Violence

Even as national and international human rights activists continue to sound the alarm over the rise in anti-activist violence, the Colombian Right in all its iterations, from Juan Manuel Santos’ “center-right” government to Uribe’s “hard-right” opposition coalition, has done little to stem the bloodshed other than turn the other cheek or exploit the violence for its own political ends.

Though the Santos administration attempted to bolster some protective measures for social leaders, it also proved hell-bent on denying the political and systematic nature of the crimes, likely because recognizing it would mean accepting the failure of its security policy as well as of the peace accords, and giving in to its political opponents. In a speech delivered on the one-year anniversary of the agreement, Santos asserted that there was no evidence of a systematic pattern of attacks against social leaders. “The motives are diverse and in many cases unrelated to their social and political activity,” he claimed. Despite the backlash from human rights activists, his Defense Minister, Luis Carlos Villegas, doubled down on this assessment just a month later, chalking up the murders not attributable to the FARC or the ELN to petty disputes over land, illicit rents, and even “líos de faldas”—roughly, “lady trouble.”

In other instances, the Santos government attributed the killings to organized crime and illicit economies, once again attempting to depoliticize the violence. In fact, it consistently refused to recognize the Uribe administration’s failure to dismantle the paramilitaries’ criminal networks and chose to emphasize the differences between them and their successor groups to "avoid granting them political recognition.” To that end, the Santos government used the labels “criminal bands” (Bacrim), an Uribe-era legacy, and, starting in 2016, “organized armed groups” (GAO). This language serves to break these groups’ discursive ties with Colombia’s paramilitary past and thus portray them as new agents of organized crime whose sole raison d'être is to exploit illegal rents through illicit crops, illegal mining, extortion, among others.

Though uribismo shares Santos’ apolitical diagnosis of targeted violence, it has a somewhat different take on its causes, one that likewise buttresses its political agenda. Despite the presumed involvement of legal actors, the uribista discourse consistently invokes the specter of “illegality”—a catchall term for illegal activity that breeds violence and threatens public safety—which it claims has proliferated due to the peace agreement.

Moreover, while Santos attempted to diffuse the blame for the assassinations, his uribista detractors harp on one cause in particular: drug trafficking. In their view, the Santos administration has given FARC dissidents, ELN and EPL combatants, and the paramilitary successor groups, which they still refer to as Bacrim, free reign to jockey over the spoils of the drug trade, leaving a trail of dead bodies in their wake. They also mention illegal mining to a lesser extent. This rhetoric serves to discredit Santos, justify their relentless opposition to the peace deal—especially the provisions concerning voluntary illicit crop substitution—and set the stage for a rightward shift on security policy.

In addition to denying the political and systematic nature of the violence and manipulating its causes for political gain, both the Santos government and uribismo have also criminalized social leaders. This is precisely what happened when Petro claimed that paramilitary forces were slaughtering his supporters. Rightwing politicians and voters of all stripes set out to disprove the slain leaders’ connections to his campaign and to provide alternate explanations for their murders. One of most common strategies was to brand them as guerrillas, but in the case of Petro’s murdered field organizer Ana María Cortes, they went so far as to suggest that she was involved with the AGC, which the current government calls the Clan del Golfo. Former Defense Minister Villegas announced that the police were conducting an ongoing investigation into her “criminal ties.” Human rights activists saw these declarations as a blatant and unfounded attempt to smear Cortes and absolve the government of any responsibility in the matter.

A Potential Return to “Democratic Security”

Despite its differences, the Right and Center-Right’s discourse serves to depoliticize and trivialize anti-activist violence. It erases the political causes of the killings and paints them as the result of isolated events that occur in a generalized context of “illegality,” all while criminalizing the advocates themselves, in order to make the murders banal or even justifiable. This rhetoric echoes the logics that sustained Uribe’s “democratic security” policy, a hardline, anti-terror strategy that bears a chilling resemblance to national security doctrine, between 2002 and 2010. During this time period, the government imposed an anomic political order fixated on stamping out the insurgency as well as its alleged accomplices at all costs in order to “achieve national security.”

When he first took office in 2002, one of Uribe’s first policy moves was to declare a national “state of exception.” Under this state of exception, anyone who even remotely challenged the status quo, including Uribe’s political opponents, human rights activists, independent journalists, and judges, was branded a terrorist and became the object of political persecution. State agents colluded with paramilitary groups to “neutralize” civilians and then pass them off as military targets in order to pad the guerrilla kill counts, “prove” the effectiveness of Uribe’s security policy, and justify continued military aid from the United States.

One of the most notorious cases was the now well-known “false positives” scandal, in which the Armed Forced extrajudicially executed about 10,000 civilians and disguised the victims as combatants of illegal armed groups between 2002-2010. These assassinations were the result of perverse incentives within the military, which essentially tied promotions and rewards to “increased efficiency” (read: higher kill counts).

In a similar fashion, persecution against social leaders was thinly veiled as a crackdown on the guerrilla and its accomplices. Such was the case of Luis Eduardo Guerra, a social leader from the “peace community” of San José de Apartadó, who was murdered along with his wife and son in a joint military operation with a paramilitary force on February 21, 2005. Uribe subsequently dismissed this community as FARC supporters and refused to recognize the state’s responsibility for the crime, offering yet another example of how his government discredited human rights violations against social leaders.

As uribismo returns to the Casa de Nariño with Duque at the helm, social leaders and human rights activists across the country have serious cause for concern. His coalition’s current rhetoric suggests an impending return to democratic security, not to mention that Uribe himself implied that the violence would not be occurring if the policy were still in place. Ernesto Macías, President of Congress and uribista senator, all but confirmed this fear at Duque’s inauguration when he resurrected the age-old uribista claim that “there is no civil war or armed conflict in Colombia, but rather a terrorist threat against the state.” Duque did little to assuage these fears during his own speech, proposing a “pact for legality” aimed at achieving “citizen security.” The policy’s reinstatement would mean not only diminishing protections for leaders who focus on victims’ rights, land restitution, the substitution of illegal crops, illegal mining, collective rights, and oppositional politics, but also outright repudiation. It will mean that la paz nos va a seguir costando la vida—peace will continue to cost us our lives.

Lucía Baca is a Research and Policy Associate at Colombia Diversa’s Peace and Armed Conflict Division, where she monitors the implementation of the peace deal. She has a BA in Global Affairs and Latin American Studies from Yale University.

Javier Alejandro Jiménez González is Researcher at Fundación Paz & Reconciliación, where he focuses on anti-activist violence. He is a Political Scientist from National University of Colombia and has a postgraduate degree in Humans Rights from Superior School of Public Administration.