Mara Telles isn’t your average Brazilian politician. First, she is a woman running for the Minas Gerais state legislature, where 71 out of 77 deputies are men. Then there’s the fact that in a country where 49% of federal deputies have relatives who hold office, neither she nor anyone in her family has ever run. On top of that, she is not a lawyer, engineer, businesswoman, landowner, or any of the other professions that largely populate Brazil’s institutions; instead, she’s a university political science professor. Her claim to fame, other than her scholarship, is her early 2018 appearance on the reality show Big Brother Brasil. When she was voted off, she exited the stage with a shout of “Fora Temer,” in reference to President Michel Temer, who took office via the 2016 parliamentary coup. Other than running for the regional presidency of the Brazilian Political Science Association, she had never thought of running for office. But she chose to run now at the urging of her students, because, as she explained to me, “Brazil is going through a rapid process of the destruction of [our] rights and the dismantling of its institutions .”

Something else makes Telles different from the average Brazilian politician: her social media presence. Historically, Brazilian politicians have relied on face-to-face contact with voters, and since the 1970s, television ads. Although most politicians today have social media accounts, few appear to manage their accounts themselves, instead delegating the task to aides. And as a 2016 study found, only 18% of politicians’ social media accounts routinely responded to comments or inquiries from their constituents. Telles, on the other hand, considers herself “a heavyweight on social media,” who has always enjoyed “expressing my opinions freely, spontaneously, and with a dose of humor.” Her following exploded after her reality show appearance, and today she has over 220,000 followers across all her social media platforms.

Telles is part of an emerging trend among Brazil’s leftist parties—not only the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT) of former president Luis Inácio Lula da Silva and his successor, Dilma Rousseff, but also smaller parties like Telles’s Partido Comunista do Brasil (Communist Party of Brazil, PCdoB) and Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (Socialism and Liberty Party, PSOL). Together, these three parties have stood most consistently against the coup and imposition of structural reforms and austerity by Temer’s government. And in the spirit of the anti-establishment mood among Brazil’s electorate, they have begun to recruit a new type of candidate who looks a lot like Telles—university educated, with a large social media following.

If you listen to the U.S. or U.K. media, it’s not the Brazilian left that is reinventing itself, but rather, the “pragmatic” or “non-ideological” center. In June, a starry-eyed article in the New York Times profiled some of the “fresh faces” challenging “Brazil’s old political guard” but failed to mention that every candidate profiled was affiliated with RenovaBR, a “civic group” founded by a coalition of businessmen, led by investment banker Eduardo Mufarej, that claims to abhor right-wing and left-wing “radicalism” alike, but whose supposed “centrism” is nothing more than a market-friendly, pro-business agenda. RenovaBR is closely connected to business interests in the United States through its ties to Americas Society/Council of the Americas (AS/COA), which recently hosted a forum in New York for these “fresh” faces. In other words, this “renovation” of the neoliberal “center” uses new faces—with a few token black or brown, female, or candidates with disabilities to show their commitment to diversity—merely to promote old ideas.

What makes Left candidates different from these elitist “centrists” is their direct engagement with voters through social media. To be sure, the use of social media is not unique to the left; while the neoliberal “center” may eschew it, right-wing politicians like presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro and his politician sons, among others, use social media to disseminate poorly-researched memes and conspiracy theories to their hundreds of thousands of followers. But these right-wing candidates do get something right, and it’s something that leftist parties have caught on to as well; like Donald Trump, they recognize that voters crave a direct connection to politicians, or, put more simply, they want to feel like their voices are heard. While the corporate media decry such “populism,” this strategy of direct engagement seems to be resonating with voters on both the Left and the far right, and for the Brazilian Left, it comprises a key aspect of Leftist parties’ attempts to renovate themselves in the wake of the setbacks of the last three years. This is a renovation with precedent: candidates like the PSOL’s Jean Wyllys, a former reality show contestant who was elected in 2010 as the first openly gay member of Brazil’s Congress, have already shown that the fame conferred by television or social media can be a powerful tool to gain exposure. Even more importantly, their similar backgrounds and platforms offer evidence of the unity of the Brazilian Left on the eve of the most important presidential election in a generation.

Fernando Horta, PT candidate for federal deputy from the Federal District, is another academic with a large social media presence running for office in Brazil’s upcoming elections. He recently defended his doctoral thesis in International Relations at the University of Brasília. Unlike Telles, Horta does have one family member who once was a candidate for public office: his father ran for Porto Alegre’s municipal council in the 1990s but received fewer than 100 votes. Like Telles, Horta has an active social media presence. Although he started using social media as a way to facilitate dialogue with his students, after the 2013 demonstrations protesting inadequate, expensive social services he began speaking out about politics on Facebook. By 2018 he had nearly 21,000 followers across social media platforms, and his posts against the post-coup government’s attacks on education, culture, and social programs caught the attention of the PT. They invited him to run for office, and he accepted because he was looking for “a more classically leftist party, one that would take up the proletariat’s struggle again.”

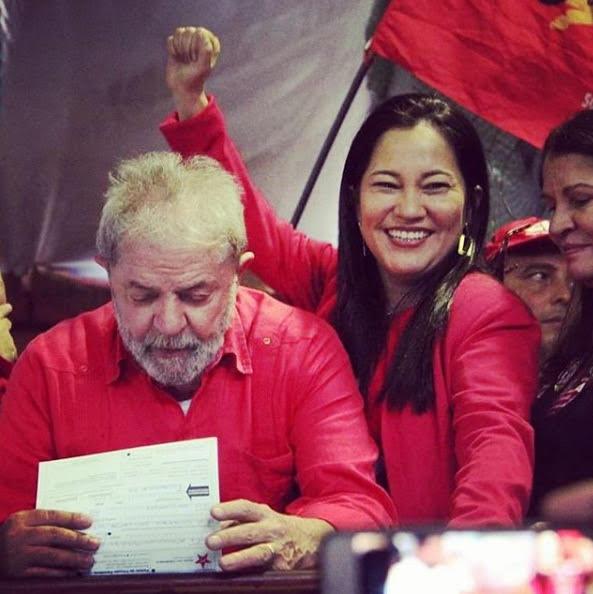

At the same time, Elika Takimoto is running for state deputy for Rio de Janeiro for the PT. A public school teacher and accomplished author, she hails from Madureira, a working-class neighborhood in the Zona Norte of Rio. Like Horta and Telles, she is an academic, with degrees in physics and philosophy, who is active on social media, with 250,000 combined followers on Facebook and Twitter. Her recent writing on Facebook has focused on the challenges facing Brazilian public education since the coup. One of her posts—an ironic response to an agent who told her it would be hard to keep getting her writing published if she kept talking so much about politics on social media—caught the attention of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who called and asked to meet her. One thing led to another, and at Lula’s urging, she decided to run for office. “If I don’t run, who will? The old politicians don’t represent us very well,” she says.

Candidates like Takimoto, Horta, and Telles lack nothing in enthusiasm or outspokenness, but it’s hard to tell if that will be enough for them to get elected. As Takimoto notes, “No one knows if likes can be converted into votes.” This is a real concern, since it is likely that only a fraction of a candidate’s online followers reside in the state where they are running. A still more serious problem is a shortage of funds, both for the middle-class, academic candidates themselves, and for their parties. For all the claims that the PT enriched its campaign coffers by robbing the state oil company, Petrobras, the party has provided almost no financial support to Horta other than a one-time $3,600 payment for expenses, and smaller leftist parties like Telles’s PCdoB are even more strapped for cash. Horta posted recently on Facebook about a call he received from a PT campaign manager one morning, with a full agenda for the day ahead. The only problem was that his wife was at work, they had no one to watch the kids, and a recent Ph.D. graduate like Horta was in no position to hire a full-time nanny. Even in a country with free television time for candidates, it’s difficult to run a campaign when neither a candidate nor their party has the necessary resources. Meanwhile, candidates sponsored by the corporately-funded RenovaBR have no such problems; Mufarej’s organization offers personal stipends of between $1,200 and $2,900 per month (five to 12 times Brazil’s minimum wage) to their aspiring candidates.

In addition, despite the receptivity of Left party leaders to a new type of candidate with academic credentials and social media chops, there has been some resistance from party militants. The PCdoB, PSOL, and PT all pride themselves on their ties to social movements, but this new type of candidate has fewer ties to “traditional” social movements like unions, Afro-Brazilian groups, the landless or homeless workers’ movements, or progressive Catholic groups. Horta admits that when he was invited to run, there was a measure of resistance from some in these social movements, who questioned whether his candidacy was “appropriate or necessary” since he wasn’t “organic to the party.” Or as Takimoto puts it, some in the party see her as an ivory tower academic who is trying to “parachute in” to politics without putting in the requisite activism in the street. To an extent, this is understandable. Prior to the founding of the PT in 1980, Brazilian leftist organizations, particularly those that took up arms against the country’s 1964-1985 military dictatorship, were dominated by university students and intellectuals. In 1979, when Lula as a union president was leading mass strikes in São Paulo, he discouraged “vanguard” organizations’ offers of support and insisted that the workers’ movement remain autonomous. However, Lula eventually set aside his misgivings and embraced the support of intellectuals. The PT was founded and thrived as an organic alliance between social movement activists and leftist academics. When seen in this light, the candidacies of Horta and Takimoto are a renewed expression of the party’s historical values.

Still, these problems are less crippling than they would be in the United States. To begin with, the fact that Brazilian parties recruit candidates like these put them far ahead of their Democratic Party counterparts in the United States. Who can imagine, for example, establishment Democrats inviting a leftist academic like Keeanga Yamattha-Taylor or George Cicciarello-Maher to run for Congress? On top of that, Brazilian elections are far more open than U.S. elections to small parties or candidates who are not independently wealthy. This is largely due to the fact that they feature free TV time (based on the percentage of the vote that a party or coalition received in the last election) along with a ban on corporate contributions. And this new kind of leftist candidate, with their academic background and social media following, has other weapons in their arsenal. As a political scientist whose research focuses on voter behavior and public opinion, Telles told me that she is able to bring her knowledge to bear on her own campaign. Horta’s research, he says, gave him the knowledge to speak authoritatively on Brazil’s problems, and his experience explaining complex ideas in a classroom setting lent him the necessary public speaking skills.

More importantly, all three have electoral platforms that are far more in touch with the Brazilian people than the pro-foreign investment, banker-friendly policies that the RenovaBR candidates profiled by the New York Times advance. Takimoto cares deeply about ensuring that education, art, culture, and recreation are available in neglected working-class neighborhoods like the one where she grew up. Telles describes her struggle as being on behalf of “more opportunity, especially for the parts of the population that have historically been disempowered: black people, poor people, women, students, residents of quilombos, workers, and LGBT people,” whose rights she believes can be secured, in part, through strengthening public education from pre-school to the graduate level. Horta describes his campaign’s primary issues as “education, culture, citizenship, democracy, and the struggle for a less unequal country.” If elected, he plans to focus on promoting a reform to the country’s middle- and high-school education and repealing the 2017 constitutional amendment that froze social spending for 20 years, along with the controversial labor reform that “flexibilized” labor law to benefit employers.

Can Takimoto, Horta, or Telles win? We’ll know on the night of October 7, when Brazil’s electronic votes are calculated. But win or lose, one thing is clear: the setbacks of the last three years have led the Brazilian left to return to its roots, not only among social movements, but also among progressive intellectuals that stand in solidarity with the working class.

Bryan Pitts is associate director of the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Indiana University Bloomington. He is completing a book on the surprising but inadvertent role of civilian political elites in the demise of Brazil’s 1964-1985 military dictatorship.