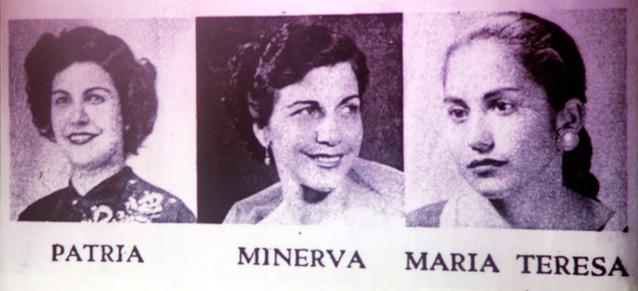

This past Sunday, November 25, marked the 58th anniversary of the horrific murders of three young women at the hands of notorious dictator Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) in the Dominican Republic. The Mirabal sisters, Minerva, María Teresa, and Patria, had been involved in the resistance movement against the dictator who, in response, ordered their deaths in the last days of his regime. Since 1999, the United Nations has internationally recognized the anniversary of the murders as the Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. This acknowledgement is an important benchmark in consciousness-raising about everyday forms of violence committed against women on a global scale. However, what is less known about that day and its history is the vanguard role Dominican women have played in feminist activism on a global scale since the end of the vicious regime and the reemergence of feminist consciousness- and activism- raising circles in the past several years in the country’s capital.

In June 2018 in the Mirabal Sisters Province (formerly Salcedo Province, recently renamed in honor of the murdered siblings), a group of women known as the Tertulia Feminista Magaly Pineda (Magaly Pineda Feminist Gathering), founded in 2016, held their monthly gathering. Many participants wore t-shirts with the logo “El feminismo nos fortalece” (feminism strengthens us). Members of the group range from teen to octogenarian; the group was founded in 2016 by filmmaker Yildalina Tatem Brache and sociologist Esther Hernández Medina and grew out of a constitutional reform effort. Meeting themes range from the highly personal (embodying feminism) to the universal (music, art, the internet) to the global-meets-local (Dominican implications of the #MeToo movement). Their meeting in the Mirabal province at the home of one of their founders focused, like all of their monthly gatherings, on their mission of addressing the lack of “permanent spaces of dialogue and reflection about feminism and women’s rights.” They toured the home/museum of the Mirabal sisters, as well as its famous garden, and spent several hours in conversation about the current state of women’s rights in the Dominican Republic and possible collaborations between women in the capital and in other provinces.

A History of Feminist Activism

The work of the Tertulia echoes women’s organizing from the late 1970s and early 1980s, when creating inclusive groups focused on consciousness-raising was a core goal of the growing feminist movement across the region. The gathering in the Mirabal Province is particularly evocative of a 1981 demonstration of feminist activists in Santo Domingo that took place shortly after the first Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Encuentro (Meeting) in Bogotá, a conference of women intended to create transnational networks of activism and combat the marginalization of women across the region. Sixteen Dominican women attended the Encuentro as delegates, representing the largest non-host delegation, leaving a considerable mark on the conference.

In a remark during the conference proceedings, Magaly Pineda, who would become the namesake of the Tertulia, compared the struggles Dominican women faced on the most basic levels with those of her Latin American colleagues. As she noted, across the region feminist was “still a harsh word which jolts people—although we are beginning to defend it.” Pineda had been prominent in women’s activism since well before the 1981 conference. At a young age she had participated in the 1965 April Revolution, where she fought against the U.S. occupation, and was a founding member of the country’s foremost revolutionary women’s group, the Federación de Mujeres Dominicanas (Federation of Dominican Women, FMD). She had subsequently worked as a professor at the national university (UASD), published on feminist issues in national and international publications, and organized educational projects and international conferences through the 1970s. She had also been a core member of the Grupo Participación Social de la Mujer (Women’s Social Participation Group), an early second-wave feminist group, and founded the Centro de Investigación para la Acción Feminista (Research Center for Feminist Action, CIPAF) in 1980. Despite her death in 2015 after a long battle with cancer, her legacy continues in the work of today’s feminists and the ongoing work of CIPAF.

One of the final resolutions of the meeting was to declare November 25, the date of the assassination of the Mirabal sisters, as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to honor their sacrifice. The celebration in Santo Domingo that followed the conference was possibly the first public manifestation of a feminist movement that had grown up in the wake of the dictatorship. It had three central goals, including making discussions that had been occurring amongst participant organizations, denouncing violence against women committed by state and societal actors, public, and expressing their solidarity with women and popular movements in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Haiti, and other countries of the Global South.

The event called attention, albeit limited, to the growing demands of the women of the Left who felt their activism for social change had failed to make even the smallest dent in conditions for women in the Dominican Republic. Prior to the rise of dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1930, women had been active across the political spectrum, and had demanded rights and greater social, civil, and political recognition. Under the dictatorship, women earned suffrage and other gains, but were defined primarily by their roles as mothers. Activists employed this gender stereotyping as a strategy to help end Trujillo’s regime and demand greater involvement in the democratization efforts of the 1960s and 1970s, decrying the dictator’s ever-increasing “intimate violations” of the home and family and demanding a return to peace and democracy in the years that followed.After Trujillo’s ouster in 1961, dictatorship essentially continued for another 12 years under Joaquín Balaguer (1966-1978) but feminist activism grew through this period and pushed back against many of the maternal expectations laid upon them by a paternalist regime, including through strengthening and expanding equality-focused feminist groups and study circles. The nascent movement—a Dominican “second wave”—also drew on a transnational-style of activism that had been a key feature of the women’s rights movement since the 1920s.

Challenging the Patriarchy, Raising Consciousness

Dominican women’s international influence has long been disproportionate to the relative geopolitical position of their nation. Today, the women of the Tertulia are working to demonstrate that despite many seeming advances in the state of women’s rights since the end of the dictatorship, gaping holes remain—including one of the highest rates of femicide in the world, wide gender-based discrepancies in educational and wage markers, and a total criminalization of abortion—many of which are clear paternalist legacies of the 30-year regime.

In many ways, the return to a defense of the word feminist, as Pineda noted back in 1981, seems to be at the core of the work of the Tertulia and other consciousness-raising circles that have emerged since the mid-2010s in Santo Domingo. The Tertulia is not the only group trying to resuscitate and support feminist activism. Another group, meeting regularly at the feminist and queer-friendly Fábrica Contemporanea café in the Gazcue neighborhood, represents a slightly younger crowd and is equally invested in discussions of gender identity, sexuality, and feminist politics. The Coloquio Mujeres RD (Women’s Colloquium RD) formed in May 2017, and they also meet monthly (every second Thursday), with significant overlap in membership with the Tertulia. Some of their earliest meeting themes included “Gender 101” and “Solidarity and Intersectionality.” Both groups use Facebook and non-social media means to organize their events and members, and operate with a model of shared responsibility for proposing and leading monthly gatherings. They are among a number of other collectives creating spaces for feminist debate and discussion in the Dominican Republic.

This type of grassroots consciousness-raising has a long history in the Dominican Republic and across Latin America. By 1983, Dominican feminists had successfully mobilized nearly a dozen women’s organizations, planned several national and international conferences, and, in the words of Pineda, worked “to make it possible for peasant women to discover together the root causes of their oppression and present condition, so as to enable them to take ownership of the knowledge of a reality that they can comprehend and transcend.” This had been Pineda’s goal with the founding of her organization CIPAF and it continues today to inform the feminist movement.

At the second Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Encuentro in Lima, Peru (1983) Dominican representatives left another lasting impression of their intense efforts. Latina feminist activist Rita Arditti claimed to have left the conference “feeling that the Dominican Republic feminists were breaking new ground and taking personal and political risks. I found their presentation to be particularly uplifting and hopeful.” Not coincidentally, it was this same year that the United Nations inaugurated its new headquarters for the International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW) in Santo Domingo. The fact that a relatively undeveloped urban center on a small Caribbean island won the bid to serve as the center of women’s development globally offered a measure of recognition to the strength of Dominican feminist organizing.

By the 25th anniversary of the death of the Mirabal sisters in 1985, Dominican feminist groups had constructed a network from which they could both celebrate their success but also demand more. By this point there were more than 30 organizations committed to feminist causes, all of which sought ways to engage in this historic commemoration. Thousands showed up to the sisters’ home in then-Salcedo to march in remembrance of their lives and sacrifice. In addition to opening up discussions of the role of women in Dominican history (being also the 20th anniversary of the April Revolution and the end of the International Women’s Decade), the year provided ample opportunities to engage in public debate about continued physical and sexual violence against women, including feminicide. In addition, Dominican women continued to be extremely active on regional and international levels, often with Magaly Pineda leading the way.

Thirty-three years later, November 25 has continued to play an important role in feminist organizing, although event formats and issues look slightly different. Last year, the Tertulia and the Coloquio Mujeres RD joined together to host an Encuentro de Abrazos (Gathering of Embraces) in Duarte Park following a larger demonstration in Independence Park denouncing violence against women in the Dominican Republic and globally. A series of events, culminating in a Festival Cultural Mirabal (in Salcedo/Mirabal Province) occupied several days, and included a performance piece organized by accomplished feminist actor Isabel Spencer. Each group has plans for this year, including another provincial gathering for the Tertulia, this time in Barahona province, and another march protesting consistent violations against women because, as journalist Susi Pola notes, to be a woman in the Dominican Republic is in of itself a risk.

Last July 15, a massive group of women and men gathered in the capital for the Caminata por la Vida, la Salud, y la Dignidad de las Mujeres: Aborto en tres casuales (March for Life, Health, and Dignity of Women: Abortion in Three Cases) to protest the Dominican Republic remaining one of only 26 countries in the world that criminalize abortion in all circumstances. Newspapers estimated that over 100 organizations brought out thousands of protestors, in part organized by a Christian alliance. In addition to the mobilization of women through the Tertulia and the Coloquio, groups that had begun feminist organizing in the 1970s and early 1980s were also present, including one of the first feminist groups, the still active Consejo Nacional Para la Mujer Campesina (National Council for Campesina Women, CONAMUCA).

The event—and the concurrent campaign—demand legalized abortion in only three circumstances: when the life of the mother is in peril, in cases of rape or incest, and when the fetus is not viable; the goal is to advance legislation that, they argue, brought women’s rights backwards to 1884. Women dying for lack of access to abortion, or at the hands of men, continues to be a severe problem in the Dominican Republic, not to mention the forms of everyday violence and street harassment (piropos) women face on a regular basis. Groups like the Tertulia and the Coloquio are working to bring light to these issues.

Remembering the Mirabal Sisters

Thirty-three years after the assassination of the Mirabal sisters drew international attention and outcry to the horrors of the Trujillo regime, the commemoration of their death stands in for an international women’s movement committed to the improvement of standards for women globally. And yet their lives, activism, and martyrdom for the cause of democratic principles represent so much more. As they championed a more open and just system for the Dominican people, along with many other women and men, their work catalyzed a local and transnational feminist movement that grew and flourished from the end of the dictatorship through the present.

In their deaths, they united Dominicans to work for an end to tyranny but also for a more just and humane world. In the continued celebration of their activism, Dominican women recognize the importance of standing up for the rights of those marginalized by political systems that favor the few. As is occurring now in the Dominican Republic through a re-energized feminist movement, their lives and deaths continue to be relevant in the struggle for equity across the globe.

Elizabeth Manley is Associate Professor of History at Xavier University of Louisiana. She is the author of The Paradox of Paternalism: Women and Authoritarian Politics in the Dominican Republic (University Press of Florida, 2017) and co-author of Cien Años de Feminismos Dominicanos (AGN, 2016) with Ginetta Candelario and April Mayes. She has published articles in The Americas, The Journal of Women’s History, and Small Axe, is a contributing editor for the Library of Congress’ Handbook of Latin American Studies, and is the co-chair of the Haiti-Dominican Republic section of the Latin American Studies Association.