Ninety years ago, the Colombian army opened fire on hundreds of banana workers, who were on strike for better conditions—killing an untold number.

At around five in the morning on October 6, 1928, the workers put forward a list of nine demands. On the first day of the strike, the commander of the Colombian armed forces appointed General Carlos Cortés Vargas as the military chief of Santa Marta and the banana zone. By the second day, Cortés Vargas was in Ciénaga with a battalion. The strike lasted two months, during which the workers briefly established popular sovereignty, deciding how best to organize themselves—“todos éramos jefes” was the way one worker defiantly responded to soldiers who asked a group of laborers who was in charge—“we were all in charge.” The striking workers tested whether or not the United Fruit Company could continue to exert power through its ad hoc network of corporations, missionaries, and mercenaries backed by the military and diplomatic power of the U.S. government.

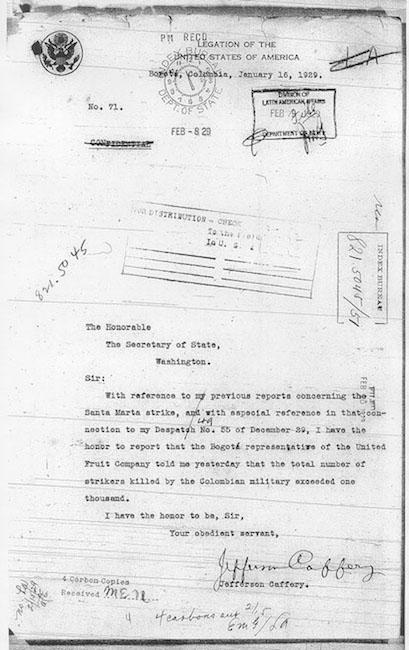

Just before midnight on December 5, Cortés Vargas received a telegram with Decree Number 1, the government’s official declaration of a state of siege. That night, the military opened fire on the assembled workers and their families at the train station in Ciénaga. After the massacre, many workers fled, seeking refuge in the mountains. But others stayed and sought to avenge the killing of their companions. Six weeks later, the U.S. embassy in Bogotá reported that “the total number of strikers killed by the Colombian military exceeded one thousand.”

While we do not have photographs of the strike or the massacre, the official archive of the United Fruit Company at Harvard University extensively documents the destruction that the workers wrought upon the company’s stores, living quarters, bodegas, and telephone lines as part of their protest.

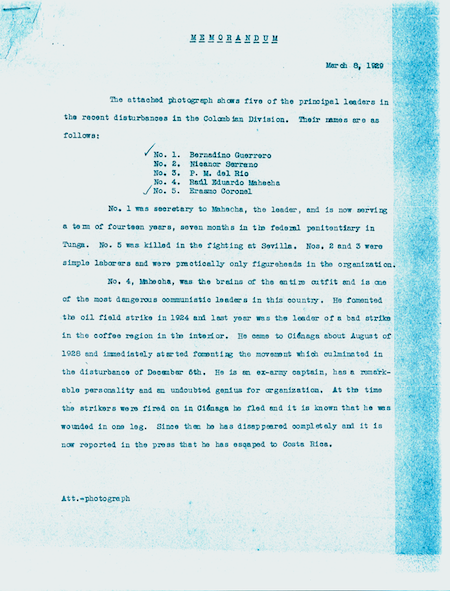

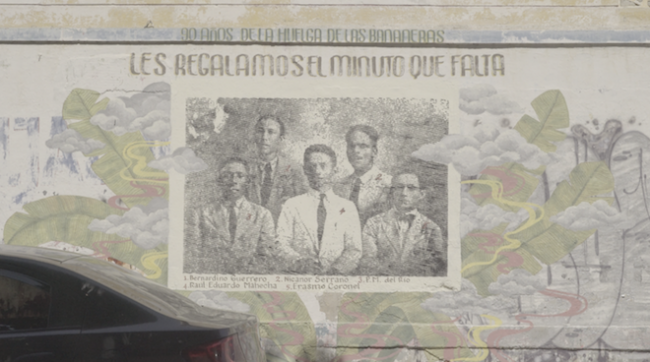

In contrast, the photo above encapsulates the way five labor organizers presented themselves to the public, and also the way that photographs were used to identify, select, and discipline (though that word seems too soft, given that the Colombian military killed one of the workers, jailed another for 14 years, and tried to kill at least one of the others). Anthropologist Philippe Bourgois wrested the photo from a United Fruit Company warehouse in Panama in the 1980s. It is a straightforward studio portrait of five men, dressed in suits and ties. But on the surface of the image someone labeled each one with a number and wrote the word “out” over two of them. The photograph had been fastened to an internal company memorandum with a paperclip, which damaged it in the corner.

How was the photograph used, where did it circulate, and what was its relationship to the paper-clipped memo that reads like a hit list? To find answers to these questions, some years ago I wrote an essay that attempts to reconstruct something of the lives of these men, their role in the 1928 strike, and how their images and the attached memo were buried in archives, extending and preserving the corporate-state violence that crushed the strike. To think about photographs that are now nonexistent—or exist but are locked in archives that we cannot access—I worked with the primary sources and the rich historiography of the strike produced by Colombianists: Mauricio Archila, Catherine LeGrand, Miguel Urrutia, Carlos Arango Z., Marcelo Bucheli, and Leidy Torres Cendales.

What follows here is a slideshow based on an exhibit that I recently curated for the Universidad de la Salle in Colombia. This visual essay aims to complement other commemorative work in Colombia and beyond. For example, historians Mauricio Archila Neira and Leidy Torres of the Universidad Nacional and the Universidad de la Salle organized a two-day academic meeting in Colombia, where I presented this work.

Today’s community of memory is also virtual. Over the past couple months, historian Robert A. Karl led a bilingual transnational Twitter commemoration of 1928, immersing himself and the thousands who follow him in the intricate details of the strike, the massacre, and its aftermath. It was through his Twitter thread on 1928 that Felipe Lozano Puche and the artist collective Jáfana Jáfana Industrias Culturales Samarias in Colombia found my 2015 essay. Since then, graffiti artist Soma Difusa has begun putting up murals in Santa Marta, Colombia, based on the photograph of the five labor leaders.

Who are these five men?

“The Mass of People Fell Like a Single Man”

During the course of this last minute, we shouted: "People, disperse, we will open fire!"

"We'll give you the remaining minute!" a voice shouted from the tumult.

We had complied with the penal code. The last bugle call ripped through the air; the multitude seemed stuck in the ground. It was necessary to comply with the law, and we complied: "Open fire!!" we shouted.

—General Carlos Cortés Vargas, Los sucesos de las bananeras: Historia de los acontecimientos que se desarrollaron en la zona bananera del Departamento del Magdalena, 13 de noviembre de 1928 al 15 de marzo de 1929 (Bogotá: Imprenta "La Luz", 1929).

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, García Márquez altered the key sentence by adding one word, so that the voice from the crowd addressed the soldiers directly: "Bastards, we'll give you the remaining minute!”

Of the hundreds that the people of the banana zone insisted that the military killed that night, when daylight broke, there were, according to official memory, just nine dead bodies lying in the plaza. Josefa María, who worked from Ciénaga to support the strike, noted that the military deliberately left each body as a symbol: “They had only left nine dead bodies, equal to the nine demands that the workers made.”

Nine demands and nine corpses. A mass movement but no photos that would allow the masses to see images of themselves acting in concert. Flashes from machine guns. Memories of the massacre written upon bodies and minds but not photographed. A photograph with numbers written upon it and a memo that reads like a hit list. Bodies disposed of under the cover of darkness. Archives with thousands of photos but none of the strike. This is how sovereign violence functioned.

After the military opened fire on the striking workers in Ciénaga, the workers destroyed several of the UFC's buildings, including the engineers' quarters in Sevilla. This is where Erasmo Coronel was killed.

Retrieving this photo from a violence that is preserved in the archive allows us to rescue the history that puts these workers—Raul Eduardo Mahecha, Nicanor Serrano, Bernardino Guerrero, Pedro M. del Rio, and Erasmo Coronel—in the center of a struggle over local and national sovereignty that exposed the violence exercised by the United Fruit Company and the governments of Colombia and the United States. The photo allows us to hear what the company tried to silence, to see what the company sought to keep invisible. Reclaiming this photo allows us to tell a story of worker-driven self and national forging that banana progress tried to obliterate.

To commemorate the massacre of banana workers in 1928, Soma Difusa, Felipe Lozano Puche, and Germán Medina the artist collective Jáfana Jáfana Industrias Culturales Samarias in Santa Marta, Colombia put up murals based on the photograph of the five labor leaders.

Kevin Coleman is working on a documentary film that uses the photograph of the five labor leaders as a window into the 1928 strike, the massacre of the workers, and the mutilation of the archive. He is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Toronto, Mississauga. An expanded version of this visual essay was published as “The Photos We Don’t Get to See: Sovereignties, Archives, and the 1928 Massacre of Banana Workers in Colombia,” in Making the Empire Work: Labor and United States Imperialism, (New York University Press, 2015); and “Las fotos que no alcanzamos a ver: Soberanías, archivos y la masacre de trabajadores bananeros de 1928 en Colombia,” in Fotografía e historia en América Latina, (Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo, 2015). Some of the primary source documents upon which this slideshow and essays are based can be found here.