In the early days of NACLA, many of its writers labored under the shadow of the Vietnam War, inspired by the anti-war movement. This context spawned a wave of research in the service of movement activists, such as the National Action/Research on the Military Industrial Complex (NARMIC). Much of this work focused on universities’ growing roles in the development of military hardware and software for use in both Southeast Asia and Latin America. Then, as more recently, students and activists needed guides to navigate the labyrinthine bureaucracies and acronyms of the U.S. military’s sales, technology, assistance, training, and relationships in Latin America and the rest of the world. From its onset in 1966, NACLA provided much of this.

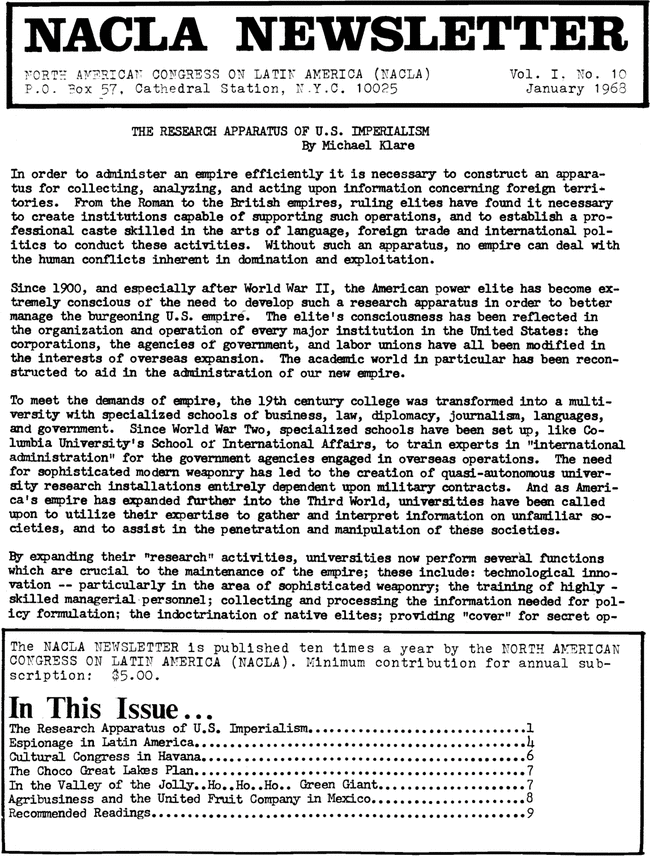

When NACLA began, not only was there no Internet, but very little detail about U.S. military contracts and sales was available outside of specialized publications. In those early years, NACLA often reproduced raw data and lists of arms deals in its pages, as well as analysis of trends and the corporate-military partnerships advancing those deals, which were not exclusive to Latin America.

Until 1974, when a post-Watergate Congress strengthened transparency, there also was no Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which has permitted researchers and journalists to obtain federal government documents that shed light on the U.S. military’s activities and U.S arms transfers. Michael Klare and Nancy Stein were early staff members and progenitors of NACLA’s research on arms sales to Latin America, and they took advantage of FOIA to expose U.S. overseas military training programs in 1976. Klare continued to write on the subject for NACLA for 30 years. “NACLA saw itself as exposing things so that movement groups would pick up the ball and carry them forward,” Klare told me recently. “It saw itself as a node in the activist community.”

In its very first newsletter in 1967, NACLA addressed Washington’s prescriptive policies for Latin America’s Air Forces. According to a Pentagon official quoted in the piece, the “primary mission of the Latin American (air) forces can be met by two basic aircraft,” both of which were U.S.-made, counterinsurgent rather than expeditionary, and available from the United States secondhand. Then and later, liberals such as Senator J.W. Fulbright, U.S. president Jimmy Carter, and Costa Rican president Óscar Arias joined the effort to stop sophisticated military aircraft sales to the region on the basis that they would lead to a regional arms race that would reduce social investment and destabilize balances of power.

Weapons transfers to Latin America occurred in diverse ways, as researchers for NACLA recounted—and sometimes helped to change. In 1974, Klare and Stein published a study in NACLA that detailed how the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Public Safety had taught more than a hundred police from 18 Latin American countries how to make homemade bombs, and how some of those police subsequently participated in death squads that murdered dissidents in Uruguay, some with explosives. The investigation—based on documents released to U.S. Senator James Abourezk (D-SD)—led to legislation that ultimately phased out the Office of Public Safety.

Since the 1960s, U.S. military aid and weapons sales have risen and fallen in alternating cycles. Vietnam-era military deployments and aid programs gave way to lifting restrictions and increased sales in the 1970s, including of sophisticated aircraft to South American nations. In the 1980s, as the Reagan administration stepped up both overt and covert intervention programs in Central America, NACLA focused its analysis less on weapons sales and more on military assistance, as well as how “soft” aid reinforced Washington’s war-making. That decade also saw NACLA expand its reporting by people living in Latin America, deepening the analysis of how U.S. policy, including arms sales, was impacting people on the ground in the region.

Klare believes the end of the Cold War changed the dynamics of the U.S. arms trade, because Washington could no longer justify subsidies or grants of weapons transfers on the basis of ideology. Instead, “people had to pay for the stuff, they didn’t get it for free in a lot of places. Not only would governments have to pay, but insurgents and warlords and all people who had been subsidized by Cold War interests on both sides. Insurgents all over world became drug dealers, ivory dealers, diamond dealers, became thoroughly corrupted.” Instead of Cold War ideological interests, the arms trade would be driven by extractivist interests in which all actors in conflict—police, militaries, narcos, mining corporations, and non-state armed groups protecting private interests—purchase weapons on the U.S.-dominated global market for guns and other small arms.

As early as the 1990s, Klare reported on Mexico and Colombia’s conflicts with Washington over the illegal gun trade from the United States. John Ross followed with firsthand reportage on Mexico’s illegal street market for guns—most of them trafficked from the United States—in 2003. A 2008 issue of the Report focused on small arms trafficking in the Americas, highlighting the United States’ role as well as that of Augusto Pinochet himself in the 1980s and 1990s and the Brazilian government since the 1990s in production and trafficking of guns in the region. NACLA authors Rachel Stohl and Doug Tuttle noted that from Brazil to El Salvador, gun violence actually increased after warfare ended as a result of the surfeit of firearms, including guns left behind by armed conflicts as well as those newly produced, trafficked, or imported into the region.

In the last three years (2015-2017), the United States exported more than $330 million worth of firearms and ammo to Latin America, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Given that Latin American countries have the highest gun homicide rates in the world, those exports have a considerably more destructive role in violence than many big-ticket sales to any region of weapons systems such as modern aircraft. More than a third of these firearms exports were to Mexico, which dramatically increased its gun purchases from the United States in 2007, at the onset of the country’s drug war and concurrent with the Mérida Initiative. The flow of military aid that came with Mérida has declined, but the high-volume gun sales to Mexican police and military forces have continued.

My analysis with Laura Weiss on U.S. arms sales to Mexico and Colombia, published by NACLA in 2017, reprised attention to the gun trade. In the Trump era, Washington is again seeking to cut aid programs, purportedly to punish wayward allies in Central America for allowing its residents to flee conditions the United States helped create, and is instead promoting sales of military hardware to Latin America as elsewhere. But aid cuts are also a means to promote profits for weapons companies, in which Latin Americans rather than U.S. taxpayers foot the bill. “The big corporations want to facilitate sales of [arms] as any other merchandise, to eliminate the Leahy Law [which prohibits aid to military and police units that have violate human rights],” Klare notes. “They want to get rid of the whole edifice, any barrier.”

Such changes will assuredly deepen the violence generating so families’ desperate exodus from Latin America. NACLA’s analyses of the political economies of arms sales, of their violent consequences in Latin American cities and rural areas, and of the organizing that confronts these policies and consequences, will continue to be essential tools for understanding and for constructing alternatives.

John Lindsay-Poland coordinates Stop US Arms to Mexico, a project of Global Exchange, and is the author of the newly released Plan Colombia: U.S. Ally Atrocities and Community Activism (Duke University Press).