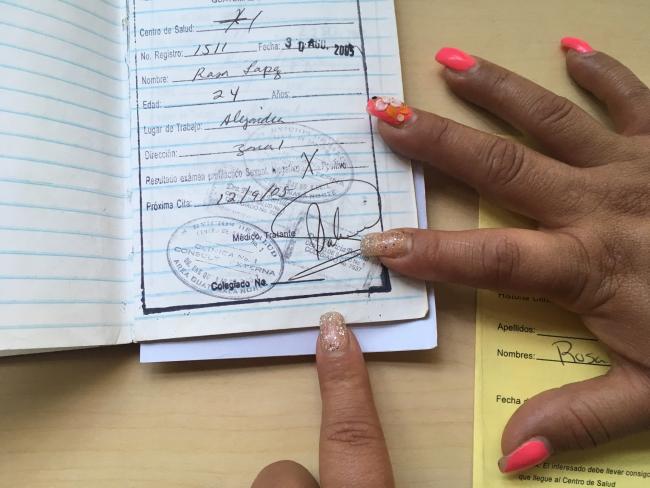

In an office full of women on a quiet street near the center of Guatemala City, Samantha Carrillo flips through a worn little booklet about the size of a passport. “I got this when I was 18 years old,” she says. The small notebook contains results from the mandatory testing for sexually transmitted infections that she received for years. Samantha does sex work, and for decades, Guatemalan law required sex workers to submit to these routine police-enforced health checks. While on paper the practice seemed to be in the interest of public health, sex workers saw it as an enormous breach of privacy rights that left them exposed to abuse by local officials. In 2012, she and her fellow sex workers successfully organized to end the policy.

Today, Samantha is the executive director and president of Mujeres en Superación (OMES), Women Overcoming, Guatemala’s first state-recognized union of sex workers. Founded in 2016, the women of OMES work to combat stigma and violence against women in their industry.

In Guatemala, 20 percent of girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 have experienced some kind of physical violence. But rates of violence for women who do sex work are much higher. Worldwide, between 45 and 75 percent of sex workers experience physical or sexual workplace violence during their lifetimes. It was this vulnerability to violence that pushed Samantha and her colleagues to create OMES in 2016.

Samantha entered the sex trade when she was 18. As a single mother, she was struggling to make ends meet—she hadn’t seen a paycheck from her job at the mall for two months, she said. One day, she was passing through one of the city’s red light districts when she ran into an old classmate. As they talked, Samantha became curious about her job, and quickly learned that sex work paid far better than any of her previous work in malls or bakeries. Samantha wanted in. Her classmate told her to come back the next day so that she could get started.

On her first day on the job, Samantha showed up to meet the woman who owned the rooms where the women worked. She dressed nicely, as if for a traditional office job: formal slacks and a blouse. But her new colleagues didn’t know the worst of it; underneath her slacks, Samantha was wearing granny panties. “You’re going to have to work without underwear because you have to use a thong here,” they explained to her. “Otherwise the men are not going to take you to bed, because that underwear is probably what they see in their house.” Samantha followed orders.

Samantha didn’t mind her job, but a few years in, something happened that forever changed her life trajectory. One night while she was working, she was kidnapped, sexually assaulted, and robbed by a group of men, she told me. She didn’t go to the police, which is not uncommon for sex workers who experience violence on the job. In fact, punitive policies and societal stigma against sex work often create an adversarial relationship between law enforcement and sex workers, according to Dr. Shira Goldenberg, assistant professor of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University, who has conducted extensive research on the criminalization of sex work throughout Latin America and in Guatemala specifically. “There's a fear of being treated differently by police because of their line of work,” she explained. “It means that violence is consequently not reported, so perpetrators can operate with impunity.”

Coercion and Impunity

The attack left Samantha reeling. “That’s when I hit rock bottom,” she told me. But her fellow sex workers were there to help her back up. Together, they decided to organize to make their work safer.

A recent study by PLOS Medicine found that criminalization of sex work exacerbates the violence and health risks associated with the industry. While sex work is legal in Guatemala, the study broadens its concept of criminalization to include coercive health checks and policing practices. Samantha said that when she or other women would take their booklets and results to the police station, some officers would take advantage of them. “They would ask you for sexual favors… and if you said no, they would say that they were going to tell the owner [of the place where you worked] that you had AIDS so that the owner would fire you.”

The police-enforced health checks that Samantha and her fellow sex workers endured for years is still a common practice in much of the world—one that has been widely criticized by human rights advocates and HIV experts. Samantha’s experience, in fact, reflects the findings of numerous studies on forced HIV testing of sex workers. The PLOS Medicine study is unequivocal and classifies repressive policing as a “basic violation of human rights,” including extortion, sexual violence by law enforcement, and forced HIV testing. It also found that such violations are “inextricably linked to increased unprotected sex, transmission of HIV and STIs, increased violence from all actors, and poorer access to health services.”

Dr. Goldenberg’s own research has convinced her that in addition to violating human rights, coercive testing actually pushes vulnerable populations away from accessing free testing and treatment. By introducing punitive measures and law enforcement into the equation, she says, “mandatory checks and testing directly undermine people's voluntary engagement in testing.”

The United Nations Development Programme policy recommendations align with extensive research on health outcomes for countries with police-enforced health checks. In its 2012 report, Sex Work and the Law in Asia and the Pacific, it urged governments to “prohibit law enforcement agencies from participating in coercive practices including mandatory HIV and STI testing.” UNAIDS lays out similar policy recommendations.

While Samantha and her colleagues knew this from personal experience, it was no easy feat to convince lawmakers to listen to them. But ending forced health checks soon became their top priority, so they began using their new collective voice to lobby Congress to abolish the practice.

Over the course of a decade, the women increasingly made their voices heard. They participated in marches, facilitated workshops about sex work and HIV prevention, and held press conferences to raise awareness about the dangers that they faced in their work. Building ties with government officials, like Congressman Edwin Maldonado Lux, was key to the women getting a foot into the halls of government.

Finally, on March 28, 2012, the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance passed a law stating that an individual’s health card can under no circumstances be used by authorities “to exercise coercive measures… nor can it be considered as a certificate of the health status of its holder.” This formally outlawed outside entities from using the records generated by health centers, and thus should have ended the practice of turning health cards over to the police for signatures. Today, testing is entirely voluntary and private.

While the government agreement was a massive legal victory for Samantha and fellow sex workers in Guatemala, practices on the ground remained relatively unchanged. Rocio Samayoa of the Legal Network and Observatory on Human Rights, HIV and Populations at Risk for HIV and AIDS says that changing the law was only half the battle. Throughout Guatemala, police were still demanding that women get their health cards stamped. Complaints were flooding in from sex workers in Escuintla, Chimaltenango, and other departments across the country up until as late as early 2016.

Rocio said that Samantha and her colleagues documented and reported the illegal practices for several years, but to no avail. “They [were] tired of constantly presenting their complaints to the Human Rights Commission,” Samayoa said, “and there was no response.”

It was at that point, in early 2016, that Samantha and her colleagues brought their case to Samayoa and the legal network. Together they filed formal complaints with the Ministries of Government and Health and again with the Human Rights Commission, submitting documentation of nationwide illegal health checks that had come to their attention since the law change more than three years prior. The Ministry of Health sided with them, and issued a memo to health centers throughout the country reiterating the law change and forbidding health centers from sending sex workers to get their test results stamped by the police. Similarly, the Ministry of Governance forbade the national police from demanding to inspect the health cards of women doing sex work. Samayoa said that Samantha had the resolutions framed, “because they mark great advances that have been made in terms of the recognition of sex work.”

Momentum and Resistance

The policy change and its eventual, albeit delayed, enforcement were the first steps toward transforming the power differential between sex workers and law enforcement in Guatemala. “We no longer have to go to get a stamp, we no longer have to go to get a signature,” said Samantha. “We no longer have any tie with the police.” The legal victory also demonstrated to Samantha and her colleagues that they could bring about real change by working together and focusing their energies on specific issues affecting their lives.

They wanted to keep the momentum from their victory going. “If we want to achieve the autonomy of working women, who are self-employed,” said Samantha, “we have to do something.”

That’s when she and her colleagues started talking with women from the Association of Domestic, Home and Maquila Workers (La Asociación de Trabajadoras del Hogar, a Domicilio y de Maquila, ATRAHDOM), who formed their own union in Guatemala 2011. “ATRAHDOM came to train us on how the process was, how a union worked, what was the added value of being a unionized woman approved by the labor ministry,” explained Samantha. “They have always been allies in the work that we do.”

After years of organizing, the women of OMES tried to get their union officially recognized by the Ministry of Labor in 2015, but they couldn’t get sufficient support for their bid. Nevertheless, with backing from Congressman Maldonado Lux, they increased pressure on the Guatemalan government. One year later, on June 1, 2016, the Ministry of Labor officially recognized OMES as a union.

Samantha saw this as a major step toward getting both the government and the general public to recognize sex work as legitimate work. It also gave her and fellow sex workers more power in the face of police and exploitative working environments. “Before, fleeing from the police was part of our life, from the owners in charge of businesses, who only exploit you,” she said.

Today Samantha and OMES continue their work, creatively funding their various projects, like pushing for the regularization of their industry and responding to individual complaints of abuse. They sell homemade popsicles and cater events around Guatemala City with food they cook in their office kitchen. The second floor of the building has been transformed into a hostel for visiting students and nonprofits. They even host biannual same-sex wedding ceremonies in the small garden behind the office. The nuptials are symbolic, since same-sex marriage is not legal in Guatemala, but they provide communal moments of levity and a small income stream for the union.

But she and her fellow union members always have their eyes on next steps. There still exists a profound and dangerous stigma against sex workers in Guatemala (and throughout the world). They believe that the government recognizing sex work as work would be another step out of the shadows. OMES is striving to get legislation passed to regulate the industry so that sex workers can enjoy basic labor rights like safety standards, paid sick days, and integration into the social security system for a dignified retirement.

Dr. Goldenberg pointed to strong research in other countries where sex workers have successfully mobilized to take collective action in their communities. She cited reductions in HIV infections and violence against sex workers, but also pointed out that unionization can be nearly impossible in criminalized environments, “because obviously, people are afraid to associate and identify themselves with this work.”

With OMES at her side, Samantha feels no shame in declaring that she is a sex worker. She believes that claiming the identity is another way to reduce stigma against her and her colleagues. With union backing, and in the absence of forced health checks, her relationship with the police has changed drastically. “I no longer see myself as vulnerable in the face of [a police officer],” she says. “I see myself as a woman who says ‘I’m working and you don’t have to say anything to me, because I have rights,’.”

Katie Schlechter (@kschlechter) is a freelance print and radio journalist based in Mexico City. She reports on human rights, migration, international law/policy, gender and LGBTQ+ issues. Prior to her freelance career, she completed her M.A. in Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University.

Additional reporting by Mitra Kaboli.

Reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation as part of the Adelante Latin America Reporting Initiative.