In December 2018, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo became the first female mayor of Mexico City, one of the largest cities in the western hemisphere. This is notable in a region still dominated by gender inequality, close to a century after women first gained the right to vote in Latin America.

Indeed, women’s political participation has greatly increased throughout the region over the last two decades. Bolivia, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Mexico have reached or are approaching gender parity in national congresses, mostly due to gender quotas. In addition to Sheinbaum Pardo’s election, in May 2018, Epsy Campbell Barr became Costa Rica’s first female Afro-descendant vice president.

Although Latin America has had several female presidents, the end of Michelle Bachelet’s presidency in Chile in early 2018 left the region without any female heads of state. With some key exceptions, this absence comes in tandem with a rightward shift across the Americas, most clearly represented by the rise of neo-fascist misogynist Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

On the eve of the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States, looking back to the roots of suffrage movements across the region is instructive in lighting a path forward for future feminist struggles. Latin American women sought not only to achieve suffrage and women’s political equality in their respective counties, but to influence the global order by building international cooperation on gender equality and critiquing U.S. imperialism. Considering how current rhetoric from the Trump administration dehumanizes and criminalizes Latin Americans, it is fitting to recognize the historical leadership of Latin American women in transnational organizing for gender equality during the first half of the 20th century.

Struggling for Suffrage

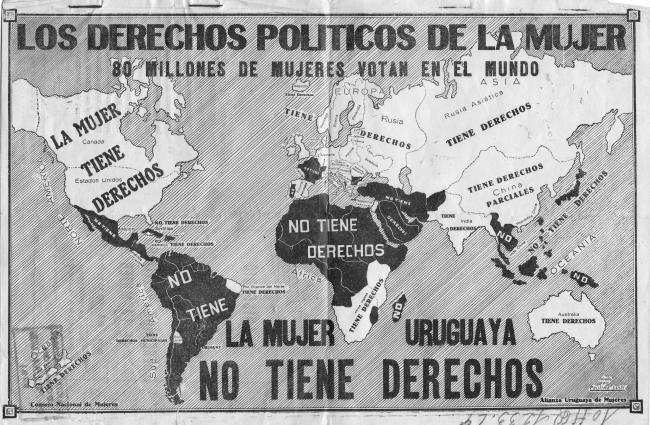

Similar to how today’s activists are organizing against feminicide and misogyny and for political representation and reproductive justice, Latin American feminists of the early-to-mid 20th century made demands for political and social rights, including more control over their bodies. This followed a liberal and secular turn in many Latin American countries, which increased women’s access to education increased in the late 19th and early 20th century and allowed some to pursue skilled professional work. Most Latin American suffragists were educated professionals who came from elite or middle-class backgrounds, with some having lived or traveled abroad. Suffrage activism began in the late 19th century and continued until the mid-20th century, when all of Latin America had implemented women’s suffrage.

As in the United States, suffrage was a hard-fought win in Latin America. In some countries such as Chile, women first won the right to participate in municipal elections in the 1930s. In others, such as Peru and Ecuador (the first Latin American country to grant suffrage in 1929), only literate women initially won the right to vote, effectively denying the vote to most Indigenous women in two countries with large Indigenous populations. Because of their own racist and classist belief systems, some of the female suffragists in these countries agreed with such policies. Today, there remains a particular need to study and document the effects of suffrage particularly on Indigenous and Black women.

In Mexico and Argentina, women spent decades organizing for the vote. With populist Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas supporting suffrage from an equality-based argument, suffrage was almost implemented via constitutional amendment in 1939. Ultimately, it failed as a result of various factors, including divisions within the ruling political party, the influence of many well-financed opposition groups, and the fear that women were too Catholic and would vote conservatively. Consequently, women’s suffrage in Mexico was delayed for another 15 years. In contrast, political stability, the influence of women’s movements and the states’ desire to seem modern and progressive, led populist presidents Juan Perón in Argentina and Getúlio Vargas in Brazil to grant women the right to vote in 1947 and 1932, respectively. In Chile, despite having broad-based suffrage movement from the 1920s through the 1940s, women did not gain the vote until years after Brazil did, with a small group of vocal women leading the push for suffrage. In all of these countries, suffrage activists spent decades engaged with regional and transnational women’s movements.

Latin American and U.S. women involved with transnational organizing had differing priorities and strategies, often framed by histories of colonialism and their countries’ place in the global order. After the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920 in the United States, some white U.S. suffragettes went on to participate in transnational women’s rights movements. Unfortunately, as various scholars such as Teresa Cristina de Novaes Marques and Katherine Marino have explained, women like Carrie Chapman Catt and Doris Stevens often brought their ethnocentrism and sense of Anglo racial superiority with them to Latin America. Unsurprisingly, their message resonated with a few Latin American suffragists who were lighter-skinned and elite in their own countries, such as Bertha Lutz of Brazil who greatly admired Catt and appeared to have no issue with stipulations that suffrage should be contingent on Portuguese literacy and thus largely restricted to whites and the upper class.

In countries where suffrage movements gained significant numbers between the 1920s and 1940s, activists communicated their ideas and organized actions through publications, such as Agitación Femenina (Feminine Agitation) in Colombia, Acción Feminina (Women’s Action), and many other newspapers in Chile. While U.S. feminist leaders tended to focus only on women’s political and civil rights, Latin American women leaders like Marta Vergara in Chile and Maria Cano in Colombia also fought for the social and economic rights of working women. This emphasis resonated in Mexico; the 1917 constitution was the first to include social and economic rights, in addition to political and civil rights. But these goals of economic well-being relied on self-determination and democracy and were thus often at odds with the goals of the United States, who in the early 20th century, intervened more than a dozen times in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to ensure their own economic and political interests.

During this time, Latin American suffrage activists involved in international organizations still sought alliances with women in places like the United States, but not without pushing U.S. women to acknowledge the effects of U.S. intervention on their countries. As Megan Threlkeld describes in her book on Mexican women’s participation in Pan-Americanism, Mexican attendees of the 1922 League of Women Voters (formerly the National American Woman Suffrage Association) Pan American conference held in Baltimore wrote to their U.S. hosts beforehand, requesting that they condemn U.S. foreign policy in Mexico. Then, like now, U.S. feminists largely ignored criticisms of U.S. policy. The conference leaders not only failed to respond to the request of the Mexican delegates, but also directed and controlled the agenda of a conference that was purportedly transnational in scope.

In response to these differences in priorities, Latin American women increasingly formed their own regional organizations such as the Liga Internacional de Mujeres Ibéricas e Hispanoamericanas (The International League of Iberian and Hispano-American Women). However, they also continued to work alongside international organizations such as the Interamerican Commission on Women (IACW), formed in 1928 and based in Washington, DC. Scholars such as Katherine Marino have documented that the IACW had a significant influence on international law and eventually on the creation of the United Nations.

At the 7th Pan-American conference held in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1933, a year after Uruguay passed women’s suffrage, participants passed the “Civil and Political Rights of Women,” or what Ann Towns has referred to as the world’s first “diplomatic resolution to recommend suffrage.” As discussed in Marino’s work, after years of pressuring IACW President Doris Stevens to support women’s economic and social rights, in particular protective legislation for women workers, as well as to adopt a more explicit position on peace and anti-fascism, Chile’s Marta Vergara and the U.S.’ Doris Stevens successfully collaborated on the passage of a women’s rights resolution at the 1936 Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Peace in Buenos Aires. Two years later, at the 8th International Conference of American States, held in Lima, Peru in 1938, IACW participants lobbied for and successfully passed the Lima Declaration in Favor of Women’s Rights, which stated that women have the right “to political treatment on the basis of equality with men and to the enjoyment of equality as to civil status…” Marino’s work outlines how IACW representatives Bertha Lutz of Brazil, Minerva Bernadino of the Dominican Republic, and Amalia González Caballero del Castillo Ledón of Mexico used the language of the Lima Declaration in drafting women’s rights into the UN charter.

The UN charter, established in 1948, affirmed faith in “fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, and in the equal rights of men and women.” It was the first international agreement to assert gender equality as a human right. At the same conference, Lutz led the initiative to form the UN Commission on the Status of Women and Amanda Lebarca, from Chile, became the commission’s director from 1947-1949. During this same time, Amalia de Castillo Ledón, as Mexico’s delegate to the IACW, worked to ensure that women’s rights would be clearly defined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, as detailed in the work of Gabriela Cano. These international norms of gender equality were immediately taken up by the Organization of American States when it was founded in 1948, and influenced the passing of women’s suffrage in many Latin American countries in the late 1940s and 1950s. Thus, transnational organizing for gender equality for Latin American women played a large role in these movements’ hard-won struggle for suffrage.

The Feminist Movement Continues Today

Since the end of suffragist movements in the’40s and ‘50s, Latin American women have been working at the local grassroots level and within the confines of the UN and other international bodies like the IACW to expand the political, social, and economic rights of women. These struggles cover a wide scope, from struggles to gain full citizenship, opposition to U.S. interventionism, and the eradication of poverty and inequality, to protesting human rights abuses under U.S.-supported dictatorships. Whether organizing for LGBTQI+ and Indigenous women’s rights or organizing to combat violence against women, their activism is vast, with reverberations at the local, regional, and global levels.

Though women’s rights were included in the original UN charter, the UN did not engage in substantive work on women’s rights until June of 1975, when the United Nations Decade for Women kicked off with the World Conference on Women held in Mexico City. This conference spurred additional regional women’s organizing in Latin America, including feminist encuentros, which have occurred every few years in Latin America since the early 1980s. The UN’s Decade for Women turned into two decades, culminating in 1995 with a conference in Beijing.

Since then, as more Latin American feminist organizations have become increasingly institutionalized—in part due to relationships with UN-affiliated NGOs—ideological and organizational conflicts between activists that organize autonomously and feminists that organize in NGOs have ensued in many countries across the region. While some organizations are able to exist at both grassroots and global levels in terms of programming and vision, feminist organizing has often been limited to what international funders agree to support, thereby restricting the scope of some feminist organizing in Latin America.

Thus, as we celebrate the centennial of women’s suffrage, let us remember that both feminism and gender inequality transcended borders in the first half of the 20th century, albeit imperfectly. Suffrage in Latin America was the result of years of local, regional, and transnational organizing. Furthermore, Latin American suffragists did not simply follow the example of U.S. feminists, but carved their own path. They worked to ensure that women’s political rights became a norm upheld legally in Latin America and connected women’s political rights to their economic and social rights, at the same time as they challenged U.S. imperialism both on a state level and on an interpersonal level within organizations like the IACW.

Yet, we cannot ignore the classism and racism that permeated some Latin American suffrage movements—which continue to affect some women’s organizing today. Indigenous and Black women were disenfranchised in some countries for far too long. Many structural barriers continue this disenfranchisement today. As we reflect on this period, we must demand that international feminist movements today are affirming and inclusive of all people regardless of class, religious, sexual, and gender identities. We must also acknowledge that as the United States continues to violate the human rights of immigrants and as feminicide continues to plague our hemisphere, the United States is also turning away from the UN just as a Latin American feminist becomes its Human Rights Chief. Perhaps we could learn from Latin American feminist activists, such as those involved in #niunamas and #niunamenos campaigns and mobilize to combat feminicide, a transnational problem that affects women of color disproportionally. As history shows, while the United Nations and other international declarations on gender equality can be important in creating and enforcing norms, such declarations do not become practice without grassroots and transnational feminist organizing.

Lucy Grinnell holds a Ph.D. in Latin American history from the University of New Mexico. She teaches at Montgomery College and UMBC in Maryland.

The author would like to thank all her co-participants of the National Endowment for Humanities Suffrage Across the Americas summer institute and, in particular, Katherine Marino for her talk at the NEH Summer Institute "Transnational Pan-American Feminism and Women's Suffrage," based on her book, Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement. She also would like to thank Kathleen McIntyre and Stephanie Opperman for reading various versions of this article.