NACLA is launching a summer fundraising campaign. Click here to show your support.

The night Brazilians elected Dilma Rousseff as their first female president, people were euphoric and celebrating. Film director Petra Costa and her mother, Marília Andrade, twirled and danced in the streets. Scenes of that triumphant spinning captures the mood of Rousseff’s election victory in Costa’s third and most recent documentary, The Edge of Democracy, streaming on Netflix since June. Over the images, Costa’s melancholic voiceover puts Rousseff’s win into a larger historical context. “I was born in a world my parents wanted to transform,” she says, “and I was becoming an adult in a world closer to what we had dreamt of.”

From frenzied recordings of these street celebrations, The Edge of Democracy’s opening scene fast forwards to images of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva handing himself into authorities in São Paulo in April 2018 to comply with his prison sentence as a supportive multitude tries to prevent his arrest. Finally, Costa turns to languid, drone-captured images showing the vast and empty rooms of the presidential residence Palácio da Alvorada in Brasilia, Brazil’s capital city. There is something uncanny in the images of the quiet and uninhabited building, perhaps a trope for the filmmaker’s impressions on the actual and dramatic political conjuncture.

The Edge of Democracy is one of multiple films that have not only documented but also shed light on recent political events in Brazil that are, for many, still challenging to unpack. Costa’s documentary ponders the circumstances that prompted the dramatic shift in the country from leftist leaders to a far-right regime under President Jair Bolsonaro. Her film, much like Brazil’s history, is made out of exceptional paradoxes. As the camera wanders around the presidential residence, a symbol of the 1950s modernization and development dreams, Costa invites viewers to imagine a country where slave rebellions were viciously crushed, where more enslaved people died than were born, where the military first proclaimed the Republic, and where democracy was only truly born after 21 years of a ruthless military regime.

At the same time, Costa chronicles Lula’s trajectory as a union leader and fierce opponent of the bloody dictatorship, his three failed attempts at running for president, and his victories in the 2002 and 2006 elections. His public policies, Costa explains, lifted millions of Brazilians out of poverty, opened a door to higher education for systematically excluded minorities, and granted access to housing and healthcare to many for the first time. Lula broadened the experience of democracy, making him the most popular president in Brazilian history.

By inserting her family’s home videos alongside 1960s newsreels, Costa makes no claim of impartiality. In her film, Brazilian history is closely entwined with her parents’ leftist underground past and her own subsequent experience as a teenager growing up in a nation slowly recovering from state violence and authoritarian rule. She includes images of the diretas já campaign—a civil movement that demanded direct presidential elections in 1983 and 1984 and the most salient symbol of the fervor for a democratic transition at the time—as both a political landmark and one of her first childhood memories.

Different from the other films analyzed here, The Edge of Democracy also devotes some time to the massive nationwide marches that started as a protest against an increase in the bus fare in June 2013. “As the streets suddenly awoke after 20 years with a series of mix demands,” she says, “something in our social fabric started to change, giving birth to the deep division that would rip us apart…from this moment on, nothing would be the same.”

Costa believes that the anti-Rousseff movement that emerged in those demonstrations against fare hikes was partially the result of her previous decision to reduce the interest rate, challenging bankers and the financial system—a move far more radical than any by her predecessor, Lula da Silva. Meanwhile, economic slowdown, the global drop in commodity prices in 2011, and rising unemployment caused her popularity to plummet. In a struggle to regain support, Rousseff passed anti-corruption laws, kicking off a major investigation, Operação Lava-Jato (Operation Car Wash), which would destabilize the entire political system. As the head of those investigations, then-judge Sérgio Moro, now Bolsonaro’s minister of justice, became a media phenomenon, mounting his campaign against the Workers’ Party and former president Lula. Rousseff’s firm commitment to Lava Jato led to a reprisal by many of the traditional political parties, some of which were previously government allies. Opponents accused her of fiscal “pedaling” in the federal budget—an accounting maneuver used to give the false impression that more money was received than was spent. The outcome, in her case, is now well-known.

O Processo (The Process), filmmaker Maria Augusta Ramos’ ninth documentary, approaches these events from a different angle. The film opens with a wide drone shot that reveals the Praça dos Três Poderes (Three Powers Plaza) in Brasilia, while multitudes gathered to watch the House vote on Rousseff’s impeachment live on giant screens. The landscape is visibly divided into two halves opposing each other: a crowd dressed in yellow in favor of the impeachment, and the other side in red in support of Rousseff and against the parliamentary coup.

The film premiered in February 2018 at the 68th Berlin Film Festival, was screened at the It's All True Festival in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in April of the same year, and released in May. The first commercially successful and critically acclaimed on a list of several documentaries to deal with the topic, The Process has the aesthetic features present in Ramos previous works. In her Justice Trilogy—Justice, 2004; Juizo, 2007; and Hill of Pleasures, 2011—she examines the Brazilian criminal justice system adopting an observational approach along with reenactment and dramatization of real life situations. In her most recent documentary, Ramos is—perhaps for the first time—an observer in the strict sense, without interfering with the flow of events or recreating situations, as has been her trademark.

What interests the director the most is the procedural rituals Rousseff’s opponents in Congress carried out with zeal, appealing to the constitution and the rule of law even if they rampantly had ignored and openly broke it before. A vast majority of these white male representatives indeed faced investigations or charges for corruption, slavery, and even murder. The congress members' dramatic performances in this political theater, replayed in the documentary, seem to veil more serious reasons behind the impeachment, motives Ramos unambiguously gestures toward from the very beginning of the film. “In October 2014, Dilma Rousseff was reelected president of Brazil, potentially extending to 16 years the consecutive rule by the left-wing Workers’ Party,” the screen reads at the beginning of the documentary. Ramos seems to suggest conservative political forces and elite economic interests could not afford and did not want one more Workers’ Party administration.

Well-crafted cinematography and skillful editing punctuate The Process. As in her previous films, Ramos wanted to register how people interacted with others, in this case, within the Brazilian Senate in preparation for the impeachment trial after Congress voted in favor of it. She did not know anyone before the making of the film—there was no pre-production—and her decision to focus on the Senate was the result of former house speaker Eduardo Cunha refusing to give her authorization to film in the House. Cunha, previously allied with Rousseff’s government, was the main instigator of Rousseff’s impeachment. He was incarcerated for corruption shortly after the vote in Congress.

Ramos focuses on the multiple meetings of the Workers’ Party senate caucus, where senators discussed defense strategies and reviewed the technicalities of Rousseff’s alleged crimes. As spectators of Ramos' film, we feel it is pure theater being performed in front of our eyes, where all the protagonists with vast experience and long careers knew their roles and how to present themselves in front of the cameras. Ramos’ focus on their gestures was more revealing than their political speeches. She composes the scenes masterfully, conveying the polite but palpable tension present in the entire procedure. It becomes obvious that, despite Rousseff’ allies’ efforts and the fact that the accusations against her had no real weight, all the opposition parties and interests were committed to removing her. Nothing Rousseff’s articulate lawyer or senators of the Workers’ Party could argue would influence a final result that, in the vein of Kafka’s The Trial,had been decided since the beginning.

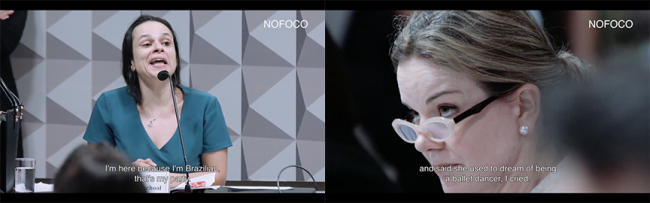

Ramos avoids crass didacticism. She did not identify groups or players by name; what matters the most is the dynamics of the game that unfolds before spectators’ eyes. In one of her briefings to the Senate, Janaina Paschoal—the conservative lawyer who co-authored the petition for Rousseff’s impeachment—screams and gesticulates, her face twitching, her frenzied movements as bare imitation of an electronic church pastor performance. Gleisi Hoffmann, then-senator for the state of Paraná and president of the Workers’ Party, stares at her, serene. The scene is an unconcealed contrast between the two women and what they represent.

Douglas Duarte’s Excelentíssimos, released last November, is also made up of contrasts. The production that began as a documentary about the functioning of Congress changed its course the day that, by order of judge Sérgio Moro, federal police agents took former president Lula da Silva to testify on March 4, 2016. Duarte decided to record Rousseff’s impeachment proceedings, and right after finishing the shooting, he realized there was something missing in the story he aimed to tell. He then decided to go back to 2014—the presidential election, corruption scandals, and the political alliances the Workers’ Party made to win that election. For Duarte, Rousseff’s reelection victory in October 2014 was, as much as for Ramos, what propelled the mechanisms that would lead to the impeachment. The prospect of one more Workers’ Party administration was not well-digested by its then principal opponent, the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democracy Party).

Through a clear narrative, Duarte’s voiceover masterfully chronicles the intricacies of the two sides and their political alliances throughout the congressional procedures and vote on Rousseff’s impeachment. One scene shows social and women’s movements supporting Rousseff; right after, the scene switches to a meeting in Congress of a group of her detractors: ultra-conservative, religious, white men praying and chanting before discussing their next political moves.

Rousseff’s impeachment, Lula’s arrest, the radical division between the Left and Right in Brazilian public life and the rise of the latter to political power—do these issues really lend themselves to clear, sharp answers? Despite the diversity of style and the artistic choices of the directors of these films, the three documentaries all inquire about the causes of these events. Costa seeks her answers in the spurious origin of a country ravaged by injustice and social differences, which have only been kept alive and recycled throughout the twentieth century. Ramos and Duarte look for explanations in the mistakes the Workers' Party made—from its alliances with conservative smaller parties to govern to the illegal agreements its members made with big construction companies to its alleged pillaging of the state oil company, Petrobrás—helped undermine the party’s popularity. Yet the three filmmakers still seem to sympathize with the Workers' Party’s policies that, despite small and big shortcomings, have done much to repair centuries of inequality, racism, and violence against the poor in Brazil.

These films are ineludible documents to understand Brazil’s recent history, even if they are not able to totally answer the questions that inspired their creation. For us, who watch them in despair and disbelief, two scenes are worth recalling. In the first, Duarte interviews Carlos Marun, a member of Congress with the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party), formerly allied with the Workers’ Party. Marun explains that independent of what the parties were going to say during the debate in Congress, he would vote in favor of impeachment, as it is a hybrid tool—half political, half judicial. He then says, visibly amused, that even if Rousseff had stolen a popsicle, he would be in favor of removing her. He thinks she is too unpopular and that Brazilians had grown tired of her.

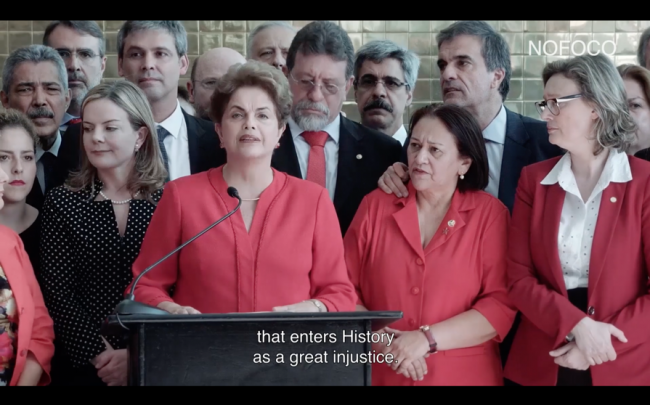

The second scene shows a visibly upset Rousseff at a press conference after a long Senate session from August 9 to 10, 2016, when senators upheld the indictment against her in a 59–21 vote. Ramos captures that moment masterfully, and Rousseff comes to be the most articulate of all the men and few women who speak in The Process. Her integrity remains intact against the blatant cynicism of those who judged her. “The coup,” she says, “is against the people and against the nation. It is the imposition of intolerance, injustice, and violence.” Quoting Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, she adds, “We are not happy, that much is certain. But why should we also be sad? The sea of history is agitated, threats and wars we are bound to overcome, break them in half, cutting through tem as keel would.”

Paula Halperin is Associate Professor of History and Cinema Studies and Director of the School of Film and Media Studies at Purchase College, SUNY. Her scholarly work lies at the intersection of visual culture, nationalism, and the public sphere in Brazil and Argentina from 1960 to 1980. She was the recipient of a National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Stipend 2019 for the project, “Dancing Days: Nationalism, Soap Operas, and Dreams of Modernization in Authoritarian Brazil. 1978-1979.”