After days of anxiety and protests, President Evo Morales has narrowly won Bolivia’s presidential election. To win, Morales needed a 10 percent lead over his closest rival, former President Carlos Mesa. Morales received 47.08 percent of the vote and Mesa 36.51 percent, giving him a lead of 10.56 percent, according to the country’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal.

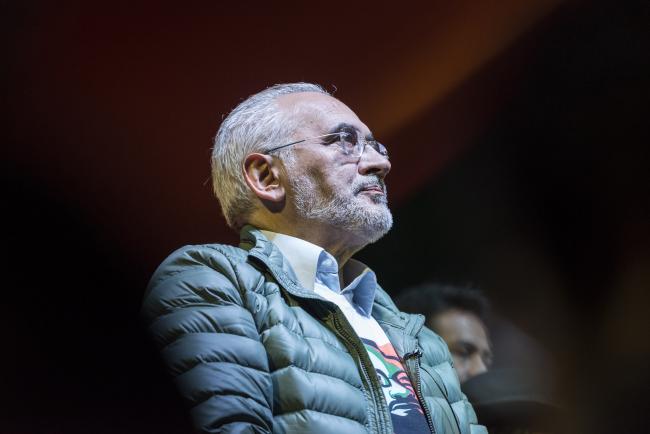

For the first time in Morales’s nearly 14 years in power, the race was close from the beginning. Mesa ran on a platform largely focused on accusing Morales of being undemocratic.

“I think these are the most important elections of recent times, perhaps since the restoration of democracy in 1982,” said the national coordinator of Mesa’s coalition, José Antonio Quiroga, “because what is in play is the future of democracy itself.”

On Sunday, when limited preliminary results were in, both sides immediately declared victory. Morales registered 45 percent of the total, while Mesa registered 38 percent. As Morales failed to win by a 10-point margin, Mesa proclaimed that a runoff was inevitable. But Morales insisted that he was sure that when “the last vote is counted,” he would prevail. The remaining votes were nearly all from rural areas, and in the past, Morales has won the majority of these votes handily.

Accusations of Fraud

Mesa’s alliance, Citizen’s Community (CC), had announced that they expected fraud even before the voting began. "The civil disobedience that accompanied the election was a chronicle foretold, as the opposition planned to react in the event of any Morales claim to victory, fraudulent or not,” said Bret Gustafson, associate professor of anthropology at Washington University.

Early Sunday night, Bolivia’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal suddenly suspended the vote count without explanation. The calls of fraud immediately became louder. “The longer the counting suspension lasts, the greater the chance of manipulation of the results,” Quiroga said.

According to preliminary reports from election monitors, the process itself appeared largely transparent and they saw no evidence of fraud. But by late Sunday night, monitors from the Organization of American States, or OAS, tweeted their concerns about vote-tampering, insisting that the electoral tribunal explain why it had interrupted transmission.

Almost 24 hours later, the tribunal updated its figures, granting Morales a lead of barely over 10 percent, just enough to avoid a runoff. The tribunal did not provide a reason for the delay, so the European Union delegation and several diplomatic missions joined the OAS in demanding an explanation. “The unexpected interruption of the electronic vote counting has sparked serious concerns that need to be fully and swiftly addressed,” the EU wrote.

These worries were reinforced when the vice president of the electoral tribunal, Antonio Costas, resigned Tuesday afternoon, calling the decision to suspend the vote count on Sunday night a folly and saying he had neither participated in it nor agreed to it.

The baffling failure of the electoral tribunal to clarify what had happened amplified existing distrust. The opposition flooded into the streets in nine cities across the country. They set fire to local vote-counting centers in Potosí, Tarija, Santa Cruz, and Sucre. On Wednesday, civic committees across the country organized an indefinite general strike.

As these protests became more violent, Mesa tweeted, “The government, with its decision to ridicule the will of the people, is alone responsible for the violence that threatens Bolivia.” Mariano Perez, an 18-year-old from an upper-middle class neighborhood in La Paz, echoed Mesa. “We are here to defend our right to the vote,” Perez said at a demonstration in La Paz on Tuesday. “They changed the results by five percent in one day. That’s fraud and we won’t permit it.”

On the other side of the police line separating the opposition from government supporters, 18- year old Laura Copeticón repeated the same phrase: “I’m here to defend my vote.” She continued, “We don’t want racist people back in power. They have always taken advantage of us.”

In response to demands for clarification about the vote counting process, Bolivia’s Minister of Foreign Relations Diego Pary Rodríguez, officially requested that the OAS initiate an audit of the election results, and the organization agreed to undertake it.

If the results had indicated a second round, it would have been the first runoff in Bolivian history. Journalist José Rafael Vilar argued in La Paz’s daily newspaper, La Razón, that a vote for Mesa will be less a vote for him and more a vote against Morales.

Change in Bolivia

Morales himself isn’t the only one in danger. His party is, too. As has been widely expected, the composition of the legislature will be similar to that when Morales’s party, the Movement Towards Socialism, known as the MAS, first came to power. As of Monday when a preliminary count of 83 percent of the votes had been registered, the MAS had lost the two-thirds majority it has held since 2009, as well as its absolute majority in the House of Deputies, while just preserving it in the Senate.

The biggest surprise was the unexpected third place win by Korean-born evangelical Chi Hyun Chung who garnered over eight percent of the vote, bypassing right-wing Senator Óscar Ortiz. As was customary in Bolivian politics before Evo Morales’s presidency began in 2006, the inter-party horse trading has begun. Ortiz announced his support for Mesa, and Chi and Mesa were in negotiations. That could’ve made for strange bedfellows as Chi wanted Mesa to abandon his commitment to LGBT rights.

Undoubtedly, voter fatigue with Morales’s government has set in. Many young people have never known any other government than Evo Morales. As Vice President Álvaro García Linera sees it, “When the policies of a left government enable class ascendancy, the collective imagination of what is possible changes. If we don’t take this into account, those whose lives have improved because of what you have done can vote you out of office.”

Copeticón said this is especially true for her generation. “Most young people are utterly dependent on social media for their information,” she said. “A lot of it is not true, and few of them know our history.”

If Mesa had won, he would have faced the challenge of negotiating with the powerful social movements that forced him out of office in 2005. The majority of them still back Morales. Mesa’s campaign has also pushed a strong environmentalist message, which has kept agribusiness in Bolivia’s economic motor, Santa Cruz, at a distance. Their interests — based in soy and cattle-ranching — have found an easy alignment with Morales's government policy of expanding the agricultural frontier. Bolivia has seen remarkable stability under Morales, largely based on the expansion of extractive activities in hydrocarbons, minerals and agriculture, with often disastrous consequences for the environment and local Indigenous peoples.

“The 500-year-old model based on primary material extraction has come at an enormous ecological cost,” Quiroga, of Mesa’s Citizen’s Community, said. “We want to change that development pattern to an environmentally friendly one.”

This would be difficult to achieve since Mesa has promised not to change basic economic policy. “We won’t do anything to threaten monetary and financial stability,” Quiroga said. “We believe we can make economic corrections without devaluing the currency or take away the payments to the elderly, pregnant women and school children.”

The Future for Morales and the MAS

Under Morales, one of South America’s poorest countries has consistently shown some of the region’s highest economic growth rates, according to the IMF. The economy has expanded three-fold, and investment in public services and infrastructure has been unparalleled in the country’s history. Poverty has decreased by half under Morales.

Social inclusion under the Morales government has been striking. Signs proclaiming “all of us are equal under the law” hang in many businesses and public spaces, in an effort to diminish Bolivia’s entrenched racism towards its Indigenous population, the highest percentage in the Americas. The current dispute over the vote reflects the deep historic divides over future directions in Bolivian society, often along race and class lines. A successful professional who is Indigenous told me, “When Evo was elected, the world got better for Indigenous people like me. All the privilege the light-skinned upper class in this country had was suddenly threatened.”

The rights of women have also expanded. Legislative parity for women is the law, although at the municipal level achieving parity has been fraught with violence against women. The government passed one of the region’s strongest laws against violence against women, but the country still struggles with an alarmingly high rate of femicide.

While Morales’s symbolic impact as modern Latin America’s first Indigenous president cannot be understated, his tenure has been accompanied by a steady concentration of power. “Evo is the element that permits ideological, identity and practical unification in the MAS,” Fernando Mayorga, a Bolivian political scientist, explained.

Morales’s style of governing comes from the vertical peasant and trade union structures where he got his beginnings in the late 1980s. These tend to be top-down and male-dominated, as well as heavily shaped by patronage relationships, although the grassroots do occasionally push leadership aside.

MAS party activists are cognizant of the leadership challenges the party faces. “Renewing leadership is absolutely necessary,” Vice President García Linera said. “We made a big mistake in not training new leaders earlier.”

The economic challenges ahead are significant. Bolivia currently facing a growing budget deficit, declining international reserves, an increase in public debt with still-low international prices for commodities, as well as a currency held artificially high against the dollar.

“The next government will be unstable, precarious, and with no clear mandate,” Mayorga said. “Without a majority in Congress, and an unfavorable economic situation, any government is going to be hard pressed to move their priorities forward.”

This piece was co-published with Latin America News Dispatch.

Linda Farthing is a journalist and researcher who has co-authored three books on Bolivia. She has written for the Guardian, the Economist, Al Jazeera, Inter-American Dialogue, and the Nation.