A well-known deafening hum and noxious petroleum fumes pollute the air. Amid widespread power outages in the wake of a series of strong earthquakes, Puerto Ricans on the Big Island once again have turned to generators to power their basic needs and activities. But the seismic shocks throughout Puerto Rico create far more than just infrastructural and cultural destruction: embodied memories of trauma during and after Hurricanes Irma and María have resurfaced, as have deep concerns with an unsustainable and untenable fossil-fueled, centralized electric grid that continues to position Puerto Rico as a sacrifice zone of energy colonialism.

The recently published book, Aftershocks of Disaster: Puerto Rico Before and After the Storm, features an eerily apt earthquake metaphor for describing the current situation. Since late December, seismic readers and residents reported regular tectonic plate activity. These disturbances reached a new level, however, at the turn of the new year. On January 2, a 4.7 magnitude earthquake was registered in Guánica, in southwestern Puerto Rico, which became the site of a 5.8 quake four days later on January 6—a religious holiday, celebrating the Three Kings. The following day, on January 7, not far away, several additional sizable disturbances occurred, with temblors as high as 6.4 and 6.0. Aftershocks and new quakes have persisted, including a 5.9 temblor on January 11. In all, more than 1,000 quakes have rocked the southern area in just two weeks, with many reaching 4.5 or greater magnitude. News reports and residents’ social media posts documented and continue to record their completely changed surroundings, while at least three deaths, many injuries, and devastated infrastructure have been reported. Among other effects, school reopenings have been delayed because of the urgent need for building inspections.

The impacts are gravely concerning, as is the urgent need to ensure that interrelated discourses about earthquakes, energy extraction, and an unworkable electricity grid are amplified and seriously addressed. Popular discussions about the quakes point to deeper anxieties and real problems regarding Puerto Rico’s centralized electricity system that repeatedly fails local residents—both in everyday situations and during the emergencies posed by hurricanes and earthquakes.

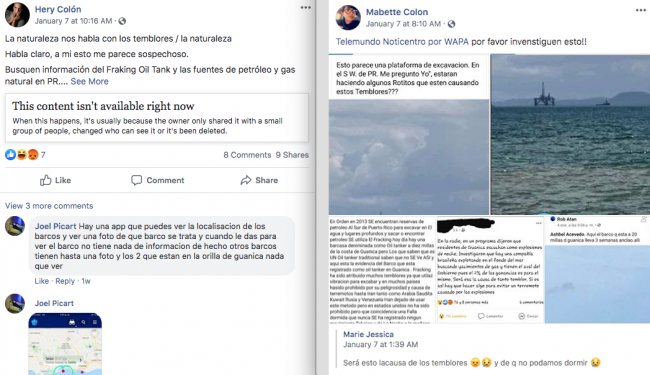

In social media posts and other communication, we have observed that those with geological knowledge agree that, in this specific case, this magnitude of earthquakes and the swarm of aftershocks have not been caused by fracking, but by the energy released by the movement of tectonic plates. Yet, the popular emergence of the fracking narrative and suspicion should not be minimized or dismissed as ignorant. Given the history of experimentation and cover-ups that Puerto Ricans have experienced over the years—including being used as guinea pigs for developing capitalism in Latin America, birth control testing, cancer research, bombing and chemical- and biological-warfare, and, most recently, large-scale solar projects for green capitalists—suspicions that fracking caused the earthquake phenomena should not be sidelined.

Such an explanation emerges as a result of this colonial history, along with a critique of current plans to rebuild the existing grid with continued reliance on fossil fuels, especially methane gas. This so-called “natural” gas infrastructure is central to the Puerto Rican government’s energy transition plan—spurred by the fossil fuel industry—to expand electricity generation using fracked gas from the continental United States. Although the Puerto Rico Energy Policy Act, made law in May 2019, requires that 40 percent of the Big Island’s energy mix come from renewables by 2025, there is a competing gas push and calls to transform the colony into an energy hub for methane gas. This ongoing fossil fuel advocacy does not bode well for hurricane and earthquake preparedness and resiliency, as we see in the aftershocks of this ongoing disaster. For example, the Costa Sur plant, a major power provider on the Big Island, is seriously damaged and has shut down to protect worker safety. We suspect the call to close the plant may be part of a strategy to gain support for a new gas plant in Palo Seco or elsewhere, by the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) utility’s executive director, José Ortiz. EcoEléctrica, a privately owned methane gas power plant, also was damaged and contributed to the power outages.

Energy generation through methane gas combustion entails risks related to seismic activity that can lead to leaks and explosions. This is a danger to public health and the environment. Research on “induced” and “natural” earthquakes marks an urgent area of study to better understand and to call out the consequences of extracting and burning fossil fuels. Past studies document connections between increased seismic activity after fracking activities, as toxic fluid injections can cause faults to slip, contributing to earthquakes. While we are not seismologists—we are a communication scholar, anthropologist, and lawyer, respectively—and we believe in the precautionary principle. This principle states that if some action, or inaction, carries a potential risk of harm, we should exercise prudence and caution with proceeding and perhaps abandon that option or approach all together. As Puerto Rican scholars who have studied environmental, climate, and energy issues preceding, during, and following the 2017 hurricane season, we are accustomed to pushing back at dominant narratives and rhetorical tropes that simplify, disinform, and harm Puerto Ricans in the Caribbean and in the U.S. diaspora. Accordingly, we seek to amplify growing concerns among local residents that link these earthquakes to ongoing resistance to extractivism and imported hydrocarbons.

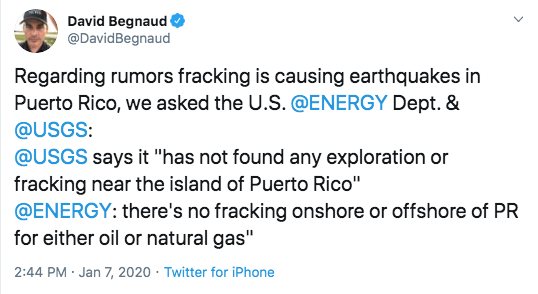

The most recent series of seismic events in Puerto Rico has raised red flags for many who wonder what could have caused so many earthquakes of such high magnitudes in such a short period of time. Journalist David Begnaud tweeted that the U.S. Geological Survey and Energy Department reported on January 7, 2020: “There’s no fracking onshore or offshore of PR for either oil or natural gas.” In 2013, the U.S. Geological Survey found gas and oil excavation and extraction potential in the Puerto Rico-U.S. Virgin Islands area. In this “Exclusive Economic Zone,” as it is called, the “assessment team” found 19 million barrels of oil and 244 billion cubic feet of “undiscovered” and “recoverable” hydrocarbons. Notably, this U.S. Geological Survey report found that this area would be conducive for conventional (non-fracking) extraction.

On the morning of January 7—shortly after beginning the day with horrible quakes and aftershocks, though thankfully no tsunamis—residents on our social media pages began raising questions about possible ties to fossil fuel-related activities, given evidence of an industrial watercraft in the waters off the coast of Guayanilla. On Twitter and Facebook, several conversation threads discussed sightings of a large ship anchored off of Guayanilla’s coast. Fishers in the area, who know the land and seascape intimately, had reported hearing explosions in the water, around the area where many of the strongest quakes occurred. Local radio programming also has reported these odd noises.

As more individuals and groups express concerns about increased build out of methane gas infrastructure, we hope the language of “natural” will be avoided—both in terms of describing these series of seismic disasters, especially given the long-standing socio-environmental-political conditions that make this situation so severe, and in terms of methane gas, which is anything but green and “natural.” As Puerto Ricans relive the trauma and memories of María, serious concerns about the future of their energy system and the consequences for human health and the environment require urgent attention. Ties between unsustainable energy systems and the oppressive power dynamics they support not only create toxic environments that can harm people’s physical health, but also their mental health. In response to such mental health challenges, the Taller de Psicología Social Comunitario, which offers healing sessions to community members, has been visiting towns in impacted areas, including in Salinas.

As Salinas-based lawyer and environmental justice advocate Ruth “Tata” Santiago (one of this essay’s authors) explained in an email to various renewable energy supporters on January 7, 2020, the current Grid Modernization Plan for Puerto Rico—prepared by Puerto Rico’s Central Office of Recovery, Reconstruction and Resiliency—promises to only perpetuate these continual aftershocks. Santiago rightfully critiques the billions of dollars to be spent on “hardening” the grid. Part of the plan involves multiple methane gas facilities, including in San Juan, Mayagüez, Palo Seco, and Yabucoa, contributing to Puerto Rico’s increasing reliance on this fuel and liquefied “natural” gas (LNG) ports and pipelines, which would account for nearly 45 percent of all energy as part of the plan. The surge in methane gas infrastructure proposals and projects in Puerto Rico poses exponential risks during earthquakes and aftershocks, such as gas leakages and explosions. Strong earthquakes are not uncommon in Puerto Rico and in the Caribbean region more broadly, as efforts to commemorate ten years since the 2010 earthquake in Haiti remind us. As Santiago concluded, “We need to avoid this man-made disaster in the making.”

We have witnessed how top-down, outsider-knows-best emergency management functions when catastrophe strikes in Puerto Rico and in other areas of the Caribbean that are impacted by atmospheric and geologic hazards. It is important to continue to bear in mind the failures of the Red Cross and other international aid organizations in previous emergency contexts. Those looking to support Puerto Ricans and recovery efforts financially should consider supporting local community mobilizations to transform Puerto Rico’s electricity grid in favor of small-scale solar alternatives. Even as power is being “restored,” tens of thousands of households are targeted for “load shedding,” as PREPA implements selective interruptions in service to keep the grid from crashing yet again. Meanwhile, collaborative collectives and networks such as Queremos Sol, the National Institute for Energy and Island Sustainability, and the RISE partnership are working in solidarity with Puerto Ricans to sift through the fossil-fueled mess. And, in doing so, they are struggling toward seismic shifts to transform their realities.

To support relief efforts that advance local community self-determination, please consider contributing to the Brigada Solidaria del Oeste.

Catalina M. de Onís is a faculty member in the Department of Civic Communication and Media at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. She is the author of several book chapters and journal articles, including “Fueling and Delinking from Energy Coloniality in Puerto Rico,” published in the Journal of Applied Communication Research (2018).

Hilda Lloréns is a faculty member in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Rhode Island. She is the author of Imaging the Great Puerto Rican Family: Framing Nation, Race, and Gender during the American Century (Lexington Books, 2014).

Ruth Santiago is an environmental and community lawyer who lives and works in Salinas, Puerto Rico. In 2013, she was an Earthjustice clean air ambassador. She is a recipient of Sierra Club’s 2018 Robert Bullard Environmental Justice Award.