This Sunday, Peru will vote to assemble an entirely new Congress after dissolving the body last September for the second time in the country’s history. The first was in 1992 by jailed strongman Alberto Fujimori. With the new election, Congress has a chance of no longer being Fujimorista majority. For many in Peruvian society, that is reason to celebrate, including the Shipibo-Konibo Pueblo, an Indigenous people that live along the Ucayali River in the central Peruvian Amazon. Deep in the heart of the Amazon rainforest, in the jungle port city Pucallpa, organizers and political figures of the Shipibo-Konibo Pueblo see this Sunday’s elections as something much more—an opportunity to finally, for the first time in Peruvian history, have Indigenous Amazonian political representation at the national level.

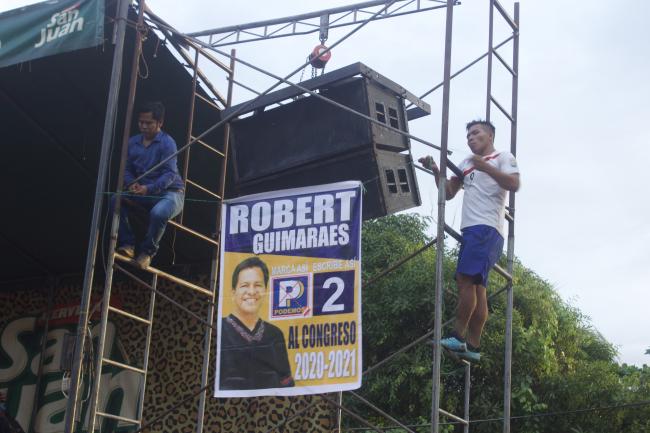

At the heart of this push is Robert Guimaraes Vásquez, a 46-year-old Shipibo political leader and activist, with a long history of fighting for the protection of Shipibo-Konibo territory against multinational extractivism. When he left his small Shipibo community at the age of 12 to move to the city of Pucallpa—to escape the palm oil harvesting that was deforesting his community—he spoke only Shipibo. Now, he is running for Congress to represent the Ucayali Department—the home of the Shipibo-Konibo pueblo, one of the largest Indigenous groups in the Peruvian Amazon. If elected, Guimaraes will be the first Indigenous Amazonian congressman in Peruvian history.

Many Shipibos are understandably ecstatic about Guimaraes’s candidacy, seeing him as someone who could finally promote legislative change to protect the Amazon—both her rivers and trees, and her people. Guimaraes and his supporters believe that, if elected, he would be a much-needed voice not only for the Shipibo-Konibo pueblo, but for the Indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon at large. But some Shipibos in the Ucayali wonder how Guimaraes can truly represent the interests of various Amazonian communities, and are skeptical of his true motives. Last month, I had the opportunity to sit down with Guimaraes and ask him: In 2020, will the Amazon finally have a political voice at the national level in Peru?

A Voice for the Amazon

On December 15, 2019, I met with Ronald Suárez for lunch in a parillada in Yarinacocha, a small city near Pucallpa where many Shipibo migrants from nearby communities live. Suárez is the president of the Consejo Shipibo Konibo Xetebo (the Shipibo Konibo Xetebo Council, COSHIKOX), the Shipibo regional political council based in Pucallpa. As Suárez ate his giant grilled steak, he calmly and cooly told me that Guimaraes’s candidacy is important because “we want to bring Indigenous voice, the voice of the Amazon, to Congress, because we are historically excluded.” For Suárez, Guimaraes himself is secondary to this concept of a vocero amazónico, the idea being that Guimaraes will be able to represent the Amazon in its entirety —not just Shipibo-Konibos, but everyone.

But who is Robert Guimaraes Vásquez? I tried to push Suárez to delve deeper into the man who aims to represent Peru’s Amazonian Indigenous population. “Why don’t you just come and meet him yourself?” Suárez asked me as he finished off the last of his refresco camu camu. Suárez explained that Guimaraes was hosting campaign events all day: Currently, he was at a youth soccer tournament hosted by his campaign, later that afternoon he was going to do a caravana aquática around Lake Yarinacocha, and that evening would be his campaign party with a live Shipibo cumbia band. Suárez did not have to twist my arm: I was ecstatic to come along for the ride.

Guimaraes is 46 but looks like he’s in his late 30s. He was warm and handsome. At the soccer tournament and the campaign party, it was obvious he was the man behind the event because of the giant plastic banners hanging from the fence and the stage with his face smiling down. But he was just having a good time with his community here, floating from family to family and pouring out San Juans, a beer brewed locally in Pucallpa. Many recognizable faces within the Shipibo political community were also present at the tournament: Walter Lopez, the founder and president of ASOMASHK, Pucallpa’s newly-formed Shipibo-Konibo Shamans Workers Union; Roger Wilder and Claudio Sinuiri, secretaries of ASOMASHK; Barnabé Ventura, head of communication at COSHIKOX and owner of a major Shipibo radio station in Yarinacocha; and various renowned ayahuasca maestres from nearby Shipibo communities along the Ucayali River and Lake Yarinacocha. Players were wearing jerseys that read “COSHIKOX” across the back —the consejo Shipibo-Konibo’s women’s soccer team.

At the soccer tournament, I was introduced to Irene Guimaraes, Robert’s younger sister and one of his main campaign organizers. She was young and beautiful, and was clearly enjoying herself. She took me and my friend under her wing and we ended up spending the rest of the afternoon and evening with her and her friends, fellow campaign organizers. When Irene is not working for her brother’s campaign, she is a teacher at a Shipibo school in Yarinacocha, where she teaches following an “intercultural-bilingual” educational model. She believes that access to an educación intercultural-bilingue (IEB) is a basic human right, and told me that it has become one of her brother’s main platform talking points. “When a teacher does not speak Shipibo, the child does not learn Shipibo knowledge and wisdom,” she said. “They want to crush us, they want to take away our identity. For this reason, we are fighting now.”

Following the tournament, Irene took me and my friend to Lake Yarinacocha so we could participate in Guimaraes’s caravan. There were more than 20 lanchas preparing to launch—large canoes with a motor that can sit 15-20 people. In our boat were Irene and two Shipibo journalists live-recording the caravan for a local news station. Guimaraes was in another canoe, standing at the bow of the boat and waving to his supporters in the other canoes and on the shore as we cruised around the lake. Lake Yarinacocha—an oxbow lake that used to be part of the Ucayali River—is massive. As we sailed around for over an hour, we passed various rural Shipibo communities on its shores. Adults and children would run out and scream and wave Guimaraes’s yellow and blue campaign shirts in the air as we passed. The feeling of excitement and of hope was contagious. I did not yet know Guimaraes’s political platform or proposals, but one thing was clear: Many Shipibos in the Ucayali see themselves in him.

I did not have a chance to sit down and speak with Guimaraes during that lively Sunday afternoon, but the following Wednesday we met in a vegetarian cafe in Yarinacocha to chat. Right off the bat, Guimaraes laid out his political vision to me in three simple steps: first, elect a Shipibo into Congress to raise the Shipibo-Konibo voice to the national level; second, truly test if the Shipibo-Konibo Pueblo can unify to promote pro-Indigenous legislature, despite internal Shipibo conflicts; and third, work towards raising awareness about the impending death of the Amazon, both within the Shipibo-Konibo pueblo and within Peru’s non-Indigenous population. Guimaraes recognized that this is an ambitious goal, but he sees no other options. “We need to either save our forests, or die trying,” he told me.

When asked about the particulars of his platform, Guimaraes first pointed to the demands of the Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest, AIDESEP) as a guide, a national Indigenous organization that represents over 1,350 communities across the Peruvian Amazon. He highlights the demand to guarantee territorios integrals, the guarantee that Amazonian Indigenous land is protected from seizure by the Peruvian government or foreign companies, regardless of any supposed debts and regardless of natural resources located on the territory. This would include changing Peruvian law to grant ownership of sub-soil to communities. Currently, even if an Indigenous community has protected territory status, the government owns anything below ground, enabling them to grant resource extraction rights to third parties.

If elected, another of Guimaraes’s main initiatives will be to declare the levels of environmental contamination in the Amazon as a public health emergency. Repeatedly over the past decade, Machiguenga communities on the Urubamba River and Shipibo Communities in the Loreto Department have suffered the toxic effects of major oils spills, leading to illness and death. Guimaraes has also dedicated much of his time over the past decade to denouncing the expansion of the palm oil industry in the central Amazon, which is threatening the survival of Shipibo-Konibo communities in the Ucayali—both because it kills their livelihood, and because individuals who resist the extractive companies are often met with violence. Some communities have been completely deforested due to palm oil harvesting and are now the subject of NGO-led reforestation projects, such as the Shipibo community Santa Clara de Uchunya located about an hour outside of the city of Pucallpa.

Guimaraes also emphasized the goal of achieving political autonomy and self-governance for Indigenous pueblos across the Amazon. “In 1993, Fujimori robbed us of our fundamental right to the territory of Indigenous pueblos,” he said to me, referring to Indigenous land tenure restrictions introduced in Fujimori’s post-coup constitutional reforms. With the Wampis Nation in northern Peru having set precedent for legally recognized auto-governance in 2018, Guimaraes sees the goal of achieving auto-gobierno autónomo for the Shipibo-Konibo Pueblo by Peru’s next presidential elections as an ambitious yet achievable goal—if there is a Shipibo in Congress. Ronald Suárez told me in late December 2019 that the Shibipo-Konibo Pueblo is currently planning on formally declaring autonomous self-governance on July 28, 2021. This may also be pushed up a year if the new Congressional body approves President Vizcarra’s call for early presidential elections.

“No one has spoken for us. Always in Congress we have been represented by the mining sector and by big industry,” Guimaraes said. He sees Peru’s current political system as inherently excluding Indigenous peoples, and he believes this is something that can be changed from the inside, looking to countries like Ecuador and Bolivia as models.

“Bolivia is a good example for us,” he said. “After all, they are now a Plurinational country. Now there will always be Indigenous people in Bolivia’s parliament, from the Andes and from the Amazon. Even though the current situation is sad, and not an example for anything—this political representation will carry on.”

Guimaraes’s envisions opening up Indigenous politics in Peru via the formation of an Amazonian Indigenous political bloc. “Not only Robert Guimaraes and some members of the Shipibo-Konibo pueblo fighting against huge economic actors, no,” he said. “The eyes of global consumerism are on the Amazon. We need to create a bloc of Amazonian congressmen, so we can be stronger and win. This is my global vision.”

Guimaraes does not see himself as presenting anything particularly radical, as far as Indigenous rights and Indigenous politics go. “I am not inventing anything new. I am just going to be defending these goals that already exist,” he said. What will be radical, if Guimaraes is elected, is having an Indigenous voice at the national level who can promote and defend these goals.

“They conquered us, they conquered our territory, our minds, and our consciences. So now we need to conquest these political spaces where, for a long time, non-Indigenous people have spoken for us,” said Guimaraes. “Now we will learn that we can speak for ourselves. It is time.”

Coincidentally, the day before our lunch, when I was spending time in a small Shipibo community down the Ucayali River, I happened to hear another side of Guimaraes’s local reception. Several members of the Nueva Betania community—who asked to not be named or directly quoted in my piece—said that they do not believe Guimaraes would truly look out for their interests, were he to be elected to Congress. “They are all corrupt, even if they are Shipibo,” said one elderly community member, referring to a commonly-held belief amongst Shipibos that politicians are always bad news. “Their help never arrives to communities,” she said.

A tendency to the anti-political in the Ucayali is nothing new. It is something that I have encountered repeatedly during my time reporting on Shipibo politics in Pucallpa. Ron Suárez, the president of COSHIKOX, is often referred to in skeptical or disparaging tones. Others have expressed distrust in ASOMASHK, the shamans workers union, because of its connection to Suárez. Some well-known Shipibo shamans, such as the Ochavano family from Paohyan and the Tangoa family from Nueva Betania, see him as a non-healer who is jumping at the opportunity to control the ayahuasca industry in Peru for his own economic and political gain, as opposed to the benefit of shamans. Others—including many Shipibo maestres— do not trust COSHIKOX nor ASOMASHK because of their assumed association with Shipibo shaman and political leader Guillermo Arévalo, whose multiple sexual assault accusations are now well-known within the global ayahuasca community. Suárez—who sees the conflation of ASOMASHK’s reputation with Arévalo’s rape allegations as unfair and inaccurate—told me that ASOMASHK was denied attendance to the third annual World Ayahuasca conference because of its rumored connection to Arévalo. The conference was hosted by people from all over the world and held in Girona, Spain in mid-2019. Clearly, distrust of certain aspects of the Pucallpa Shipibo political community extend far beyond the Ucayali River itself.

I was sure this anti-political discourse was not news to Guimaraes, and I was direct about the obstacles during our lunch. Is he concerned that his ASOMASHK and COSHIKOX endorsements would do him more harm than good? More generally, how does he think he can be elected when many Shipibo communities do not trust politicians? And who is he actually representing, if that is the case?

Guimaraes was not phased when I challenged him on these things—in fact, he seemed happy that I asked. “It is true and important to acknowledge that I am not supported by all Shipibos,” he said. “But look—we are not here to make sure we get along well with this or that Shipibo. We are envisioning political representation, to raise this voice to the national level—and not only an Indigenous voice, but specifically a voice of the pueblos amazónicos,” he said. And Guimaraes raised a good point here as well. It is only logical that Shipibos are wary of politicians, because politicians and the Peruvian political system in general were designed to exclude them. That is what he and his party, Podemos Perú, are hoping to change. And in this way, Guimaraes echoed what Ron Suárez had told me the Sunday before: His candidacy is important not because he is Robert Guimaraes, but because he is a man who will be able to bring an Indigenous Amazonian perspective to Congress.

“We are in the center of global interest, but we continue to be erased in the economic plans and in the political processes. Why? Because those with power exclude us from these political processes. Because we are obstacles to their development plans,” he said.

“For the city, for the United Nations, for the World Bank, for UNICEF, for the Inter-American Development Bank, quality of life is measured by: a car, a building, the latest model cellphone, a washing machine, etc. 100% consumerism,” Guimaraes said, as we finished lunch and called for the check. “The quality of life for pueblos indigenas is healthy fish, clean rivers, intact forests, no deforestation, clean water free of contamination. This is true quality of life. We need to change the global perception.”

Guimaraes agrees that it is important to acknowledge that not all Shipibos, nor all Indigenous Amazonian Peruvians, support him. But he also does not see this internal conflict as the true enemy, when it comes to the protection and survival of the Amazon. “Our enemies are not our brothers. Our enemies are big, they are the system,” he said. “Our enemies are not here. They are probably in some tall skyscraper in London, or in New York. They are sitting around a table right now, in some building in China, saying ‘Okay, how do we invest in the Amazon?’ “

Guimaraes and his growing Amazonian Indigenous political bloc are ready to face down these enemies. Is Peru?

Jacquelyn Kovarik is a freelance journalist based in Cochabamba, Bolivia. A graduate of NYU’s Center on Latin American and Caribbean Studies and the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, she writes about social and political movements in Peru and Bolivia. Follow her @jm_kovarik