NACLA is launching a summer fundraising campaign, click here to show your support.

The Rio Grande Valley, located in the southernmost tip of Texas, faces among the highest levels of poverty and heavy immigration enforcement in the country. Bounded by permanent and temporary Border Patrol checkpoints to the north and west, the U.S.-Mexico border to the south, and the Gulf of Mexico to the east, the valley is a zone of immobility for undocumented migrants whose status confines them to the territory. Here, more than 10 percent of the population is undocumented, compared to 3.3 percent at the national level across the United States. This concentration of residents in the Rio Grande with undocumented status—mostly migrants from Mexico—has a deep effect in community dynamics and livelihoods. Sometimes intricately tied, migrant experiences and illegality—the condition of being denied full membership rights for not fitting the state-dictated criteria for inclusion—affect even those who are not undocumented. This is especially clear for mixed-status families, who negotiate differences in legal status to carve out livelihoods that are best for the group.

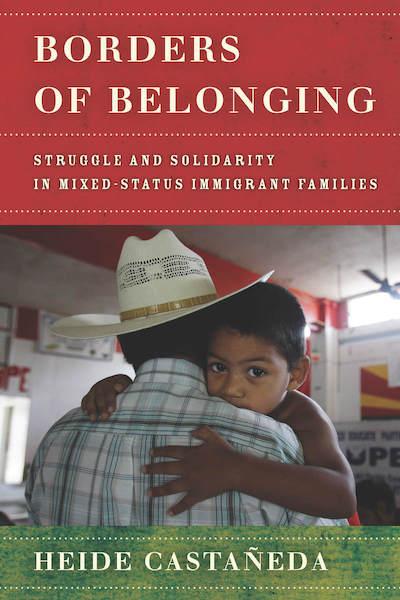

Heide Castañeda’s Borders of Belonging: Struggle and Solidarity in Mixed-Status Immigrant Families (Stanford University Press, 2019) is an intimate dive into the lives of mixed-status families in the Rio Grande Valley. In the book, Castañeda centers the families traversing the Rio Grande Valley to challenge typical understandings of illegality and precarity for undocumented migrants in the United States. The focus on how the family—as opposed to the individual—navigates illegality when not all family members are undocumented provides a novel way of understanding laws’ and policies’ effects on undocumented immigrants, their families, and communities. This, combined with the attention to geography, underscores the processes that allow illegality to take place in the borderlands.

Castañeda explores the crafting of belonging in the borderlands, both within the family and among members of the community. She delves into physical im/mobilities produced by the boundedness of the valley, as well as into how education, work, social mobility, health, and well-being are heavily conditioned by legal statuses that affect families. Despite illegal status, life goes on in the valley: mixed-status families are “resilient, socially engaged, and living as active members of their communities, while at the same time recognizing their profound marginalization.” These experiences, however, are conditioned and reproduced by the state’s legitimized presence in those spaces; whether through checkpoints, documentation (or lack thereof), social and economic mobility, accessibility of entering the job market, and other factors.

Based on a five-year ethnographic study, the book begins with the story of Michelle, an undocumented mother who could not get a birth certificate for her U.S.-born daughter because she did not have a valid form of identification. Although it had been accepted in the past, this time her matrícula consular—an identification card for migrants issued by Mexican consulates—was not accepted by the county clerk’s office. The systematic blocking of people like Michelle from obtaining a birth certificate for a child provides an example of how bureaucratic disentitlement works to prevent individuals from accessing “their statutory entitlements and infringe on their constitutional rights.” Even though Michelle’s daughter was a U.S. citizen, her mother’s undocumented status prevented her from fully enjoying the privileges and rights of being a U.S. citizen affords. Immediately, this first example challenges the notion of illegality as something experienced only by individuals, or more broadly, as something only experienced by undocumented people. Instead, this work shows that we cannot understand the full impact of the construction of illegality by only looking at the individual.

Castañeda also includes examples of how legal status affects educational and job opportunities, dating, access to healthcare, expectations of deportation and return, relations to community, friendships, and other aspects that are, as we learn, heavily mediated by the state and membership to it. In doing so, she emphasizes how communities experience the increasing “borderization” of the state, calling for a “rethinking of borders as dynamic and inhabited places” in order to “shift our focus from the stillness of border walls to the stuckness of people, and specifically the ways in which they become immobile.” The connection between families’ experiences of illegality—generally described as a multilayered sense of “stuckness”—and the strengthening of borders in post-9/11 U.S. demonstrates the ways in which the state’s presence seeps into subjugated communities.

“Borders are not just static lines of spatial demarcation, full of walls and fences and checkpoints. They are also dynamic and inhabited places full of people,” Castañeda asserts. The author juxtaposes this portrayal of the border as a heavily militarized, surveilled, and hostile space for migrants with their stories of love, resistance, and humanity, subverting traditional understandings of the border as a lifeless place (or even a place of death) to show the persistence of life in situations of heightened scrutiny. Even with this lively characterization of the border region, the “stuckness,” migrants experience in this region highlights the inhumane conditions of caging and serves to question how movement is granted to certain groups, a concept Castañeda develops in the book. Furthermore, it presents the absurdity of constrained movement—stuckness—for certain groups and, implicitly, emphasizes the reasonable demand for free movement as a human right.

She also inadvertently redefines belonging outside of the context of the white American family through telling the stories of migrant families. In doing so, we are exposed to how families in the Rio Grande Valley (and we can assume elsewhere in the U.S.) resist the settler colonial idea of a white, productive, heteronormative family, and instead form their structures in resistance to the state. Thus, the migrant, mixed-status family is an essential configuration in the long fight for dignity in the shadows. However, Castañeda’s work is not interested in deeply questioning heteronormative structures of the family, but rather in demonstrating how family plays out in mixed-status communities. Neither is it interested in seriously questioning the idea of citizenship in the nation-state, both of which are social constructs dependent on the differentiation of groups and the othering of people. In her conclusion, she points out that “we must continue to trouble the taken-for-granted construct of citizenship…,” but does not expand on the concept.

One of Castañeda’s contributions lies in legitimizing the family as a uniform social unit with potential for action and adaptation in the face of adverse conditions. By positing the family as a mediator of culture, Castañeda redefines the boundaries of social life and the ways they can be understood to gauge the impacts of policies that, though aimed at individuals, inevitably affect those around them. Inescapably, this also questions where the boundaries of family end and where non-familial relations begin. The bounded condition of the Rio Grande Valley does not prevent familial relations from developing or individuals from seeking support in members of the community. In fact, this book shows the opposite: states of precarity and illegality push the borders of belonging outward, allowing the family as a unit to collectively challenge hostile situations and to engage a kind of collective agency. In the book, we learn that, while many of the Rio Grande Valley’s inhabitants live in the shadows, these spaces are filled with life and resistance.

Javier Porras Madero is a graduate student of Latin American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.