As numbers of COVID-19 cases in Brazil steadily rise into the thousands, favela community leaders in vulnerable communities have raised concerns about the difficulties of complying with preventative measures in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas because of the lack of consistent water services. President Jair Bolsonaro’s anti-science response to the global pandemic, which has included calling the virus a “little flu” and urging businesses to re-open despite World Health Organization advice, has worsened the situation for vulnerable communities in Brazil.

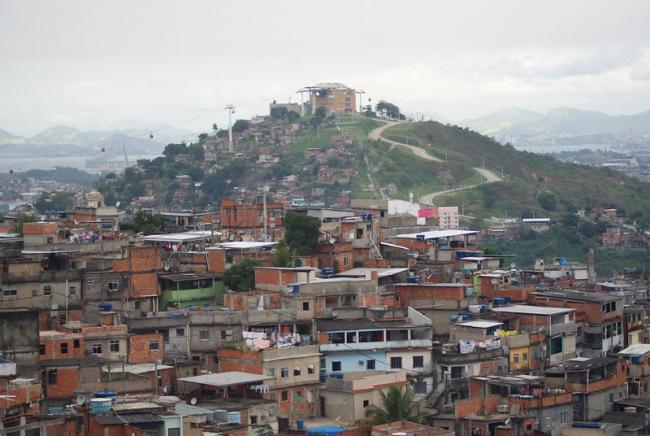

While “wash your hands” has been the preeminent preventative measure recommended by the World Health Organization, people in favelas—informal and deregulated settlements that were built due to lack of housing—in Rio de Janeiro have struggled to comply due to water shortages and a lack of antibacterial gel in pharmacies.

“The main difficulties are related to bad environmental and living conditions that are present in the majority of the low-income communities and the favelas in Rio de Janeiro and other metropolitan areas or peripheries in cities across the country,” explained medical sanitary health expert Paulo Buss. “The difficulties are specifically related to the water demand, which we know is very precarious in the favelas. And within that, there’s a difficulty to practice individual measures like washing your hands.”

Community leaders in Complexo do Alemão, a conglomerate of favelas in the north zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro where most of the population is low-income or dependent on the gig economy, have been using social media to raise awareness of the difficulties urban low-income population in containing the virus in their communities.

Mariluce Mariá, a resident of Complexo do Alemão and the founder of the NGO Favela Art, says the underlying issue is government neglect, which runs much deeper than the pandemic. “The problem is structural, and it’s been years that it’s been like this. Even though there were governmental interventions to provide basic sanitation in Complexo do Alemão, it isn’t enough because they did not count the population here accurately,” she explained. “We are more than 450,000 residents and the demand for water services is large, but the official numbers are 70,000 people, which is an incorrect estimate.”

According to Rene Silva, activist and editor-in-chief of the community newspaper Voz das Comunidades, those challenges are already being felt. “Many residents in Complexo do Alemão are complaining they don’t have water and aren’t able to prevent the new coronavirus,” Silva tweeted. “There’s no antibacterial gel in the stores or pharmacies.”

This demand issue is being compounded by an already existing water crisis in the city. Since January, residents of Rio de Janeiro have struggled with lack of drinkable tap water which prompted plans to privatize the public water services. These plans have been criticized by the community leaders who fear the water bills would be too expensive for low-income families. But even before that, the matter of basic sanitation has been fraught for most of Rio’s population: According to 2013 figures from the Ministry of Cities, 30 percent of the population is not connected to a formal sanitation system.

Buying antibacterial gel or bottled water to wash hands for prevention is also not possible for many low-income people in these communities. Tiê Vasconcelos, a beauty influencer and columnist for Voz das Comunidades, tweeted: “I can’t even buy water to drink, even when it’s infected and tastes of dirt. How will I buy it to wash my hands? Having water in the favela is a luxury.”

Globally, 785 million people lack access to basic drinking water services and 2 billion lack access to proper sanitation, according to the World Health Organization. On March 22, World Water Day, Human Rights Watch called for governments to “immediately implement measures to ensure access to clean water for all communities as a critical matter of public health and human rights” to fight the spread of COVID-19.

Other Risk Factors

Lack of water services isn’t the only obstacle to COVID-19 prevention. Under the hashtag campaign #Covid19NasFavelas, community activists have been tweeting about how advice to contain the virus does not include provisions for people who live in extreme poverty. Raull Santiago, an activist and founder of the Papo Reto citizen journalism collective in Complexo do Alemão, told UOL Notícias that official advice against the virus fails to reflect the realities that favela dwellers face.

“We need the government and the health experts to think of advice that respects and includes the people in the favelas and in marginal communities,” he said. “The way it is now, we are being excluded, ignored from Brazil’s reality because they don’t consider the reality in which we live, of extreme inequality.”

The first case of COVID-19 in a favela in Rio de Janeiro was reported a little over a week ago in Cidade de Deus (City of God), indicating that COVID-19 is already spreading in low-income communities where housing conditions, inadequate water services, and scarce health services are unfavourable to prevention.

In February, Brazil’s health minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta said the urban geography of Rio would be a problem to thwart the virus and that most places in Brazil have the same problem. “Rio is a very dense city,” he said. “We have a problem with distance and the spaces are small. Besides, there are areas of social exclusion, favelas—areas where people live very near each other, with low sanitation and extensive family nucleus that live in small spaces.”

Santiago, for example, lives in a house with five other people, as is common in favelas across Brazil. “Quarantine here is impossible,” he tweeted. “See this photo from my window. It’s wall against wall, there are houses of two, three bedrooms with six people living there. What do we do? What’s the way? Where to go with this prevention advice?”

The lack of government mitigation and aid for quarantine measures has resulted in a quick loss of jobs, compounding the poverty that increases vulnerability in the face of a public health crisis.

The problem is also economical,” Buss, the medical sanitary expert, said. “The government announced some very lacking measures, like extending the Bolsa Família safety net, I hope it happens even if these measures are lacking.” President Jair Bolsonaro slashed the program earlier this year, setting vulnerable populations to be even less supported in times of crisis.

On Monday, Bolsonaro announced the government would give the equivalent of $40 to unemployed, self-employed and informal workers for three months due to the coronavirus crisis. He also signed a provisional measure that would allow employers to pause employees’ contracts with no pay for four months.

Community Campaign Against COVID-19

In response to the crisis and the neglect from authorities, communities in Rio de Janeiro that are left out of preventative advice have organized their own campaigns and hardship fundraising to help people in the difficult times ahead.

The advice produced and spread by the Complexo do Alemão activists are specific to low-income areas in Brazil, asking residents of the area to share water with their neighbors if possible, to avoid touching each other, and to help the elderly, as they are the most vulnerable. The advice is not perfect as it still leaves people depending on the good will of others and the scarcity of dependable services, but it considers material difficulties of the most vulnerable communities.

Groups have organized hardship funds to raise money through the hashtag #PandemiaComEmpatia (Pandemic with empathy) with the intention of buying food, antibacterial gel, and water for people who cannot afford it due to loss of employment and being quarantined. Donations can also be made through PayPal.

Mariluce Mariá explained that keeping people fed is key to stopping the spread of COVID-19 in her community because it will encourage social distancing and self-quarantine and that having monetary help will fill a gap where the Brazilian government is failing.

“Most of the workers here aren’t salaried, they don’t have a fixed income,” she said. “We don’t have resources to feed ourselves, the government in our country did not give us anything to mitigate this crisis. All we have is money we earned from jobs that we don't have anymore. Deregulated workers are in an extremely vulnerable situation. Also, many people have been isolated before any national decree because we are worried about the spread of the virus in our community, and they have no income either.”

Mariluce is adamant that poverty could be the reason people break self-isolation and that monetary help must be in place before that happens.

“We don’t have funds here in Brazil to maintain everyone fed, so we really need monetary help to keep people in self-isolation. As long as we keep people fed we can keep people in their homes, but when they begin to be hungry, they will try to go outside and work and we won’t be able to contain the virus.”

Nicole Froio is a Brazilian-Colombian writer and researcher currently based in York, United Kingdom. She writes about Brazilian politics, social issues, feminism and women’s rights, and more.