When, during the presidential debates, Anderson Cooper of 60 Minutes questioned Bernie Sanders for praising some positive aspects of the Cuban Revolution, Senator Sanders replied: “When Fidel Castro came to office, you know what he did? He had a massive literacy program. Is that a bad thing?” Sanders’ question—“Is that a bad thing?”—might be considered rhetorical in a different setting, but is not so here. In fact, it cries out for an answer.

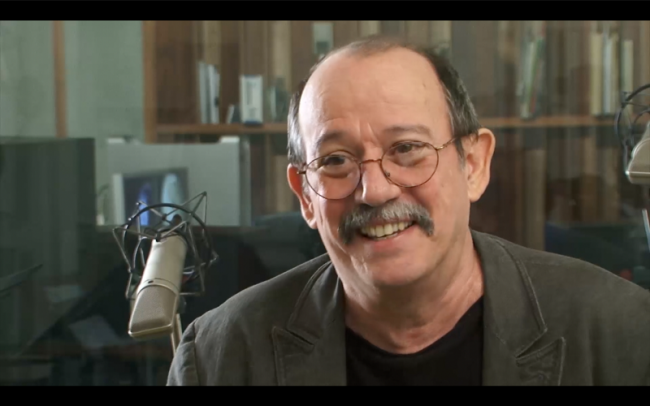

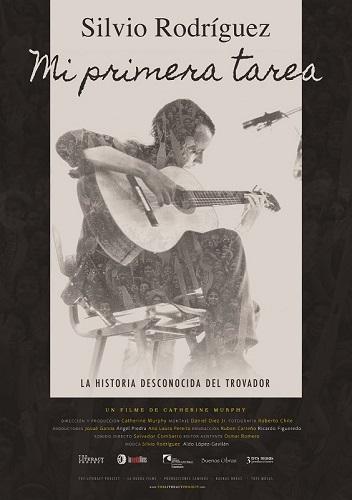

Mi primera tarea, a documentary directed by Catherine Murphy and released on September 20, seems to offer one such answer. By intertwining archival footage from the 1961 literacy campaign in Cuba with an interview with iconic Cuban singer-songwriter Silvio Rodríguez discussing his participation in the literacy saga, Murphy manages to reconstruct an intimate vision of the campaign through the memories that the musician shares.

In the documentary, Rodríguez, co-founder of the Nueva Trova movement—an important musical and cultural platform for denouncing political oppression during the rise of political dictatorships in 1960s era Latin America—does not so much fill the role of influential musician. The film focuses instead on his participation in the literacy campaign and how the experience impacted him.

“Silvio,” as Rodríguez’s followers call him, recounts how at the age of 14, he joined a brigade of over 100,000 teenagers who went into the Cuban mountains and countryside to teach campesinos how to read and write. He starts by recalling the great enthusiasm with which the Cuban people, especially the youth, embraced the idea of the campaign, even when asked to take a year off from their education to go teach reading and writing to those who did not know how. Silvio remarks: “At that age, who doesn’t have a year to give? Or two and three? So the idea was brilliant and it ignited the spirit of the young people.”

Cuba was not the first country to launch a massive literacy campaign, but it carried it out the most quickly. The Soviet Union’s literacy campaign spanned from 1919 to 1939, Vietnam’s from 1945 to 1977, and China’s from 1950 to 1980. Whether because of Cuba’s size, its considerably high literacy rates compared to those of the rest of Latin America, or the number of people mobilized (a total of about 250,000 literacy teachers), the fact remains that in less than a year, from April to December 1961, the illiteracy rate in the island nation dropped to 3.9 percent when about 700,000 adults—the majority of them in rural areas—learned how to read and write.

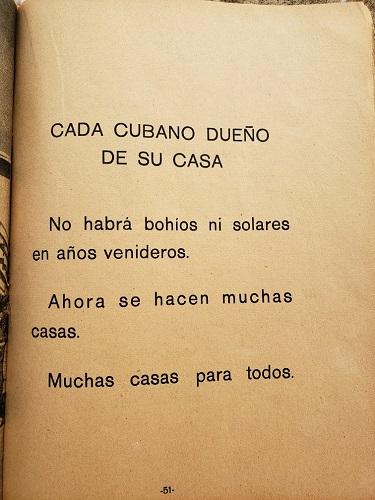

A political message about the Revolution and the new order was undoubtedly part of the campaign’s ideological foundation. In the same month that the government launched the campaign, and just one day before Cuban exiles carried out the CIA-backed up Bay of Pigs Invasion, Fidel Castro declared the Revolution’s socialist character. The campaign’s political dimension and the context in which it was born explain the viciousness with which the alzados, or counter-revolutionary groups, attacked literacy teachers, killing several of them.

Narratives about the Cuban literacy campaign have traditionally highlighted the political nature of the events, with each side recognizing teaching as an instrument of either political transformation or political indoctrination. Mi primera tarea, resisting the tendency to ideologize, points to a possible interpretation wherein the political dissolves in the personal and the affective by exposing, through Silvio’s reconstruction, the fundamentally altruistic and humanitarian character of the literacy saga.

On this more comprehensive dimension of the campaign, Murphy states: “Many lessons in the primers had political content, but many did not. It had to do with a sort of cultural pride that was being highlighted. For example, this lesson says: ‘Let’s read first and write later… In Cuba, there were Indians; they lived in huts and slept in hammocks. Hatuey was a hero.’ Here, they are celebrating the Indigenous heritage, the national identity, the roots, the original cultures.”

In Maestra, a previously released documentary about the participation of women in the literacy campaign, which is part of the Murphy’s oral history archival project on literacy, the director explores the cultural and emotional aspects of the events through interviews with eight women who participated in the campaign.

In Mi primera tarea, Murphy achieves a unique perspective by superimposing and alternating the voice and face of the interviewee with shots of archival images, mostly in black and white. Silvio evokes both transcendental and mundane moments that he seems to recall through an intimate act of remembrance. Regarding a family that he taught, Silvio recounts, “I remember that it shocked me a lot when, in a conversation I had with a father and a son whom I taught how to read and write, I realized that they did not know that the earth was round. How could I teach them to read if they didn’t even have a basic notion of the world where we lived?” In a humorous moment, he refers to his current distaste for mango, as this was his primary source of food for many months during the campaign.

References to the campaign’s epic nature are gently pushed aside when evoking a nostalgic past. On one occasion, Silvio uses the word epopeya (heroic feat), a term usually employed by Cubans to describe the Cuban Revolution as epopeya revolucionaria, or “revolutionary feat.” It is striking that he uses the term by itself—without including the word that usually accompanies it (“revolution” or “revolutionary”)—and in a much more generic and encompassing way:

“Young people yearn for epopeyas. What youth want is to be part of great and noble things that will make them grow. When they get into trouble, it is because there is no epopeya in sight. But if they see one, they will go for it.”

It is telling that references to the Revolution are minimal in the film. Instead, stories of gender and class seem to occupy a more prominent position. At the beginning of the documentary, Silvio describes his mother’s resistance to her 14-year-old going away from home to live in precarious conditions. Things were likely more complicated for female teachers, or alfabetizadoras, whose families were presumably far from accepting, let alone embracing, narratives of women’s emancipation.

However, the literacy campaign and the paradigm shift that it brought about seems to have weighed more heavily than the traditional values rooted in Cuba’s collective imaginary. The film repeatedly shows images of alfabetizadoras getting on buses leaving for the campaign. One woman washes her underwear in a river and laughs when she realizes that the camera has focused on her. Another woman gets up from her bus seat and dances sensuously. At one point, the camera captures a group of girls who have just woken up in the camp and are brushing their teeth. They all look straight at the camera without any sign of shyness or demureness.

For Cuban youth, the literacy campaign represented the chance to participate in the first important task (la primera tarea) of the Revolution and bring about their personal and generational emancipation. Murphy referred to this when commenting on the testimonials of the alfabetizadoras from Maestra:

“I heard them speak of the campaign as something very emotional, very personal, and important for their development as human beings. In particular, that notion of the 50,000 adolescent girls teaching illiterate people how to read and write, that continues to be fascinating to me. I still see it as a kind of rebellion—a ‘teenage girl uprising’—in the middle of an incredible social transformation project.”

In Mi primera tarea, Silvio describes how the campaign made a personal impact on him: “It was a way of learning what the world was like, and that experience was related to expanding myself as a human being and with positions that I later adopted.”

Murphy’s prompts consistently lead the conversation into the realm of the personal and the emotional. This freedom to address the subject from the least predictable angles—human, personal, familial, social—and not from ideological stances gives the film a refreshingly intimate dimension, allowing for the understanding of historical events beyond the paradigm of grand narratives. The interviewee reconstructs the idea of his participation in the campaign from a non-laudatory present, as the interviewer carefully crafts a visual narrative that combines mostly depoliticized archival images of anonymous stories along with Silvio’s narrative. In the backdrop, Cuban experimental music from the 1960s and Silvio’s own songs add further dimension to this unique approach.

The use of archival black and white footage of the campaign, which includes long camera takes of defiant and sustained looks both from literacy teachers and learners, helps build an intimate and almost voyeuristic gaze that brings us closer to their personal stories. Italian neorealism and cinéma vérité films directly influenced some of the archival shots, in which the camera brings out the characters’ intimate stories with close-ups and zooms.

This reference is not merely subjective. During the early years of the 1960s, moved by their curiosity about Cuba, Italian neorealist filmmakers and international film producers—including Cesare Zavattini, Joris Ivens, Roman Karmen, Chris Marker, and Jerzy Hoffman, among others—traveled to the island to become acquainted with the new directions the Cuban film industry was taking. Many of them produced a good number of films with their Cuban counterparts, who found in the European experimentalism a perfect alternative to Hollywood’s dominant model, as Michael Chanan has pointed out in The Cuban Image: Cinema and Cultural Politics in Cuba.

Many of the images used by Murphy come from the archives of the Noticiero ICAIC Latinoamericano, a newscast that preceded the projection of films in Cuban cinemas for the decades following the creation of the ICAIC (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry) in March 1959. The renowned Cuban filmmaker Santiago Álvarez directed these newsreels. Film scholars have widely documented the influence of experimental neorealism in Álvarez’s work, and in the work of many other Cuban filmmakers of this decade.

Many years have passed since the Cuban Literacy Campaign took place. Although literacy rates continue to grow from one generation to the next, still 750 million adults worldwide are either illiterate or functionally illiterate. The numbers are not particularly encouraging in the United States either, where one in five adults has difficulty completing tasks that require comparing and contrasting information, paraphrasing, or making low-level inferences, which translates into 43 million adults with low literacy skills.

Perhaps the Cuban literacy campaign was not a bad thing after all, even more so when—especially for Sanders’ critics—perceived through the intimate gaze of Mi primera tarea.

For information about educational and academic distribution of Mi primera tarea, you can contact the Literacy Project at theliteracyproject@gmail.com.

María Isabel Alfonso is a Professor of Spanish at St. Joseph’s College, New York, where she teaches courses on Cuban and Latin American literature and culture. She is the co-founder of Cuban Americans for Engagement (CAFE), an organization that has contributed to the normalization of relations between Cuba and the U.S.