This article was originally published in Spanish by Nueva Sociedad.

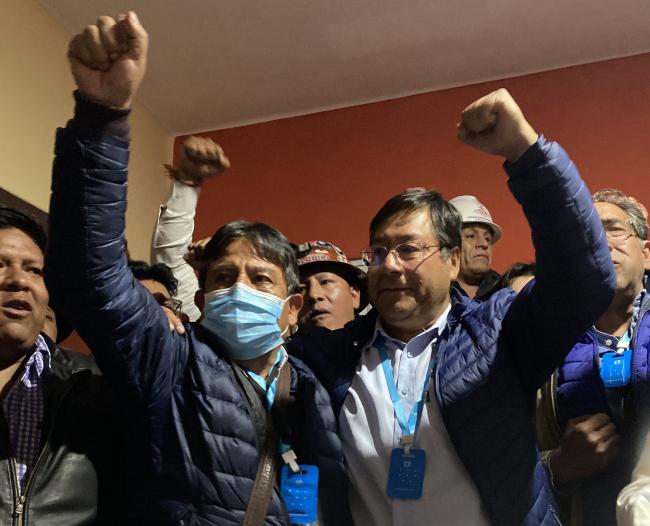

With more than 50 percent of the votes, the first round victory of Luis Arce and David Choquehuanca swiftly silenced many analyses put forward during the campaign and allows the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) to return to power just one year after having been removed by a combination of demonstrations, a police mutiny, and the intervention of the Armed Forces.

What explains this victory and the failure of center-right candidate Carlos Mesa? What does this election, which took place in an orderly way and with an immediate recognition of the preliminary results, tell us about the different political forces? To answer these questions, Nueva Sociedad consulted analysts and social researchers, who offer their short- and long-term prognoses.

Pablo Ortiz (journalist)

One year after its downfall, the MAS once again has become the dominant party in Bolivian politics. It is the only truly structured party, with political militancy and a loyal voter base. It has even weathered the exit of its top leader and founder, Evo Morales, from the political scene.

The 2020 general election is the first election without Evo Morales since 1997 and the first vote that complies with the outcome of the February 21, 2016 referendum, which barred Morales from seeking reelection again. During the campaign, many spoke about the next five-year presidential term as an exercise in transition towards a post-MAS era. But the ballot boxes contradicted the political pundits, issuing the verdict: What’s worn out isn’t the MAS itself, but rather its singular chain of command and the neverending perpetuation of Morales as president.

When the votes are fully counted, Luis Arce Catacora will have won six to 10 points more than Morales won in the thwarted 2019 elections. The following tools enabled Arce to triumph with such an unexpected lead.

The first was having the right strategy. Carlos Mesa, Luis Fernando Camacho, and other lesser forces bet on the cleavage between MAS and anti-MAS voters, each one presenting themselves as the best option to prevent the party from returning to power. But the MAS emphasized economic crisis and stability as the central axes of its campaign and prioritized consolidating its core voter base. The MAS campaigned on the cities’ outskirts, with marches and small gatherings, mixing union meetings with academic conferences to distance itself from the image that dominated Morales’s last campaign.

Arce and his strategists opted for the outlying neighborhoods, the poor and those recently impoverished by the coronavirus, and those who had joined the middle class during Morales’s 14-year government and fell into poverty again as a result of the coronavirus. Due to the pandemic and the lockdown measures, at the beginning of May, 3.2 million Bolivians did not have the means to buy food. Arce leveraged nostalgia for the MAS boom years that the worsening crisis had created.

Arce had unintentional allies coming from Bolivia’s eastern lowlands, where Morales always faced resistance. The first “helper” was the transition government. The government of Jeanine Áñez was seen as a continuation of the so-called “String Revolution,” the revolt that preceded the police mutiny and the Armed Forces’ “suggestion” that Morales step down. In January, Áñez, coasting on the honeymoon of her first 100 days, launched her bid for president in elections slated for May. In doing so, she destroyed her government’s foundations: on the one hand, an unwritten agreement among anti-Evo figures that the transition would end with a party other than the MAS in power, and, on the other hand, the cooperation of two thirds of congressional representatives and senators, who had an understanding that collaborating with Áñez would allow them win back power in the elections.

The coronavirus hit early on in the campaign. A trail of corruption busted a key myth, revealing that anti-Evo forces, too, were capable of committing acts of corruption and abuses of power. The final blow to Áñez’s popularity came in the midst of the lockdown: Her government purchased more than 100 ventilators from a Spanish firm, overpaying some four times their value for machines that didn’t even work for intensive care treatment. The successors of supposedly corrupt and fraudulent officials were not only corrupt, but also highly inefficient. Within months, in the middle of the pandemic, one health minister after another left office.

But there was another “helper.” A powerful leader promising victory had emerged in the streets: Luis Fernando Camacho, the man who led the “String Revolution” and forced Morales to leave Bolivia (after Morales resigned, Camacho announced that he was searching for the ousted president in order to arrest him, which prompted Morales’s evacuation to Mexico). Camacho took advantage of his popularity in Santa Cruz to launch his presidential bid.

The MAS and Arce still dominated in La Paz and Cochabamba, but they needed Santa Cruz—the region with the second-largest contingent of historically anti-MAS voters—not to go for Mesa, the candidate closest to Arce in the race. In 2019, the scenario was similar. Morales led the polls, and Santa Cruz was controlled by Óscar Ortiz, a local candidate aspiring for president. But in the final week, an effort to cultivate the “strategic vote” gave Mesa 47 percent of votes in Santa Cruz, bringing him close enough to Morales to debate whether or not he had won in the first round.

This time, Camacho did not suffer the same fate [as Ortiz]. Camacho rose to prominence in the streets, is religious, uses rhetoric that exudes testosterone, and foregrounds emotion more than proposals. He presented himself as the guarantor that Morales would not return to the country. This strategy inflamed the prideful Santa Cruz identity and converted it into votes. Unlike Ortiz, Camacho did not try to “nationalize” himself to win votes, focusing on Santa Cruz. This, together with the Santa Cruz youth vote, made Camacho an implacable local force, blocking out Mesa from Santa Cruz and splitting the vote with Arce. This gave Arce a more comfortable victory.

Nobody expected Arce—a technocrat, not a caudillo—to win more than 50 percent of the votes. To achieve this, he had to make some final plays that positioned him more as the first post-Evo president than as Morales’s successor. The first was having the capacity to criticize Morales’s administration and question the conditions under which “the first Indigneous president” governed. Arce has promised a youthful government, with new faces. The second move was getting the idea out of voters’ minds that the MAS would be assuming power forever. Arce has promised to govern for only five years and to “put the process of change back in motion.” And the third play was to eradicate the idea that [the return of] the MAS would mean political persecution and revanchism. Arce has promised to not persecute the police nor the military officials involved in Morales’s ouster.

Thus, the technocrat managed to reset the process of change and will be able to govern with an absolute majority in both houses of the Legislative Assembly. In order to assess whether MAS has truly entered the post-Evo era, however, we will have to see what role Morales will play when he returns to Bolivia. Arce’s authority over his legislative bloc and the country, as well as his political stability, pivot on this question. In order to close off Santa Cruz to Mesa and win, the MAS ended up raising Camacho’s profile. Now, with the territorial power he’s achieved in the eastern lowlands, Camacho will be the only opposition figure with mobilizing capacity that Arce will need to deal with.

Julio Córdova Villazón (sociologist, researcher of religious movements and political culture)

The MAS won a resounding victory in the first round. This very successful electoral performance, exceeding even the most optimistic expectations, was due to three main factors.

First, it was due to the emergency “resistance vote” of popular urban and campesino sectors. These sectors suffered various forms of violence in recent months: a) electoral violence—they were cheated out of their votes for the MAS in 2019 due to the false accusation of fraud promoted by the Organization of American States; b) symbolic violence—constant attacks from the state and from conservative and middle-class sectors on social media depicting popular sectors as “violent and ignorant hordes,” as well as some police burning the wiphala in November 2019; c) military and police violence—principally in the massacres at Sacaba and Senkata; and d) economic violence—the lockdown measures against Covid-19 were detrimental for informal economic sectors.

Second, the reconfiguration of union and campesino organizations. In recent years, these organizations were weakened by their direct relationships with Evo Morales’s government. After the president’s resignation in November 2019, these organizations rapidly recouped a vigorous social fabric and flexed their muscles by paralyzing Bolivia in early August to block the interim government from further delaying the election. This organizational fabric formed the foundation of renewed electoral support for the MAS.

Third, the political and electoral weaknesses of a fragmented Right competing with itself. Center-right candidate Carlos Mesa’s political project and campaign messaging did not seduce undecided voters in the eastern lowlands. The right-wing pro-business candidate, Luis Fernando Camacho, didn’t convince these undecided voters either. Up until one week before the election, in the department of Santa Cruz, Camacho’s bastion, 28 percent of voters were undecided, which represented 7.5 percent of the entire voter list. These were people from poor sectors who business leaders, represented by Camacho, have excluded and who suffered violence during the protests Camacho led against Morales last year. In the October 18 election, these undecided voters opted for the MAS, rejecting an elite businessman incapable of including them in his “development model.” This is why the MAS won 35 percent of votes in Santa Cruz.

With Arce at the helm, the next MAS government will be marked by economic crisis, social conflict, and the Covid-19 public health emergency. The support of at least 52 percent of the electorate does not necessarily translate into a solid social base. The MAS will not control two thirds of the Legislative Assembly as it did in previous years. This political moment requires a democratic culture of forging agreements with other political actors. And this culture is very weak, almost nonexistent, in a MAS accustomed to a kind of dominant politics that no longer exists in Bolivia.

Verónica Rocha Fuentes (journalist)

Throughout the election campaign, the “hidden vote,” which held little relevance in past elections, became evident. This hidden vote, along with the “undecided vote,” was decisive in producing a margin that, according to all projections, is more than 20 points in Luis Arce Catacora’s favor. The numerous opinion polls released during the campaign documented a much higher prevalence of this hidden vote than had historically been the case. But this research did not detect where this voting bloc would lean. Within hours of the results showing a lead for Arce, everything seemed to indicate that these votes ended up deciding MAS’s sizable margin of victory in the first round.

What was called the “hidden” vote during the election campaign could now instead be qualified as the “patient” vote. This could be useful in unpacking not only the unexpected outcome, but also the longest and most difficult election process in the recent history of Bolivia’s democracy. The unknown, patient vote is similar to the vote during the period of brokered neoliberal democracy that was known as “Bolivia profunda” (Deep Bolivia). After coming to light in recent years, this form of democracy almost disappeared completely during the year of the interim government, which put an end to the symbolic, institutional, media-driven, and corporate machinery that tends to establish the narratives of political struggle. After a year of daily and systematic stigmatization of “masismo” (or anything seeming to belong to or defend the MAS), supporters appear to have decided to hide their intentions and wait for the ballot box. Hiding out of fear, shame, or perhaps even strategically.

It was certainly a hidden vote, but also an unusually patient one. And this vote that ended up determining a sizable and undisputed first round victory was preceded by an institutional crisis, an interim government, a pandemic, the start of an economic crisis, four changes to the election date, an election day under threat from the government, last minute changes to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal’s plans, voting in a militarized country, and not having any results on election day, in order to cling—with a patience that on several occasions nearly reached its limit, but never gave in—to the last thing that stood between Bolivia and the precipice: the ballot box.

In less than a year, under the guise of electoral fraud, Bolivia has undergone abrupt, forced, and violent readjustments to its political, institutional, and media landscapes; this is all woven into a complex social fabric that, although damaged, seems to have remained intact and appeared to wait—hidden and patiently—for the right opportunity to reveal itself. Without a doubt, the main takeaway of these recent elections goes far beyond the MAS’s victory. At the very least, the results provide the minimum base needed for establishing an urgent process of national reconciliation.

Fernando Molina (journalist and writer)

There’s little doubt that the MAS’s enemies underestimated the electoral potential of the party and its candidate Luis Arce. On the one hand, the polling—which failed to show the true intentions of those who were undecided—misled them. On the other hand, this miscalculation owes itself to the inability of the political groups that represent the traditional elites to recognize the MAS as a genuine expression of the less powerful, more Indigenous sectors of the country. Instead, they have typically seen the MAS as a “puppet of Chavismo” and consider the support that it inspires as a purely transactional phenomenon.

There’s a virulent strain of racism within this shortsightedness. The traditionally dominant sectors of the country have always understood the politicization of the subaltern—which undermines the meritocratic and inherited foundations of their power—as a sudden burst of irrational behavior and greed. It has been this way since the 19th century, when representatives of the oligarchy from that period, the septembristas, complained that because of the invasion of the “cholaje belzista” (supporters of Isodoro Belzu) they had to resort to political action, which was tantamount to “savagery.”

The miscalculation we are talking about can be seen in the candidacy of Carlos Mesa, who was unable to establish meaningful inroads with Indigenous peoples. He was also part of the interim government of Jeanine Áñez, who ruled with the most privileged classes in mind: those who wanted revenge against the MAS and were used to seeing Indigenous people only as employees or a social nuisance.

The elites have shown themselves to be incapable of understanding how Evo Morales defeated them in 2005, the source of his political longevity, or why the MAS didn’t fall apart after its downfall in November 2019. Bolivia has not required property ownership to vote since 1952, but this continues to be the mentality of the traditional elites.

In this way, even with their victory over Morales last year and opportunities to establish hegemony—they had the support of the most educated and economically privileged sector of the population, as well as “powerful” backing from the Armed Forces and National Police—they lost the power they had so longed for, just one year after obtaining it.

A few elites of the racist oligarchy ruled the country from 1825, the year it was born, until 1952, the year of the National Revolution. They did so from a place of senseless and violent imposition of their will upon a humble and occasionally silent majority. These ruling conditions began disappearing during the latter half of the century, with the elites only changing superficially. To date, they remain “traditional” and tend to organize themselves into an oligarchy. This is the “paradoja señorial” or stately paradox that René Zavaleta talked about.

The most important transformation in these ruling conditions occurred when the subaltern sectors found a way to create their own form of political/electoral expression: the MAS. Since then, electoral participation has clearly been adverse for the political parties of the traditional elites. Theoretically speaking, they would be more able to sustainably recoup power through brute force, like during the 60s and 70s, but this is impossible under present-day circumstances.

Moreover, reforming the traditional elites appears to be impossible. If they didn’t learn their lesson after Morales took advantage of their mistakes, abuses, and excesses during the neoliberal period in order to defeat them, it’s difficult to imagine they will ever learn. Indeed, as soon as they had the opportunity to again prevail, they showed the same vices and the same shortsightedness they had in the 90s—if not worse, because now it’s not neoliberalism, but a particularly perverse form of hardline conservatism: right-wing populism.

At the same time, MAS would be wrong to also underestimate their adversaries in the future, even if they don’t seem to be able to generate a sustainable movement to grab power in a country as rebellious and with such a majority of Indigenous people as Bolivia. The Right is angry, resentful, and retains a large part of Bolivia’s economic capital and almost all of the cultural capital. As demonstrated last year, they also have enough power, in alliance with the middle class of military and police, to destroy the base of support of their enemies. They don’t hesitate to leave behind the framework of democracy.

Traditional elites can take advantage of the weaknesses and failures of the grassroots bloc (as did Morales’s narcissism and his government’s corruption). They can attack just when the majority bloc loses its footing, errs, becomes unstable, and stops being more than 50 percent of the Bolivian people.

Translated by Néstor David Pastor and Heather Gies.