This article was originally published in Spanish by CIPER.

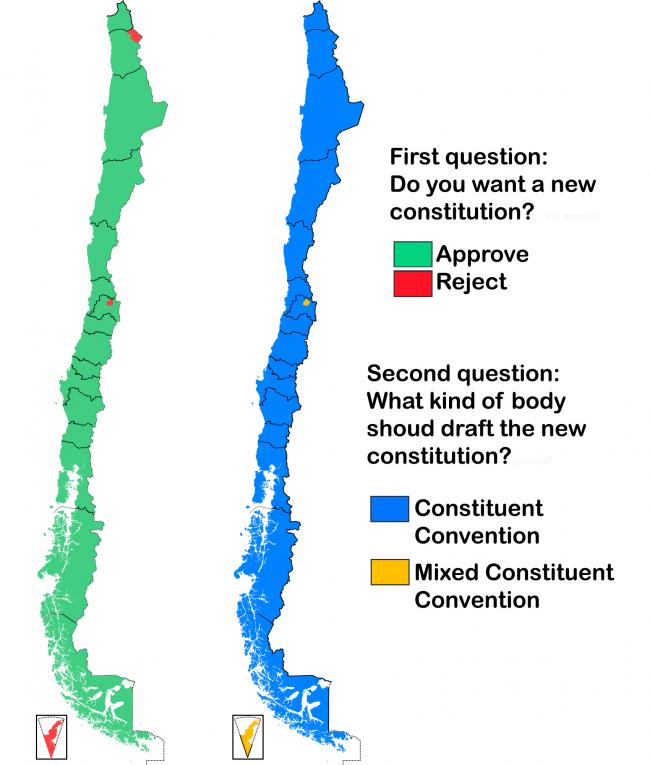

Chile’s vote in favor of rewriting the Constitution and the geographic distribution of the results offer a clear lesson: Chilean society is very unequally divided. Three comunas that hold a significant share of the country’s GDP and political power live in a bubble. [Translator’s note: Three comunas in metro Santiago voted to maintain the status quo. Chile has 346 such administrative zones in total]. There was much discussion in recent months within this bubble, in its media, its gatherings, and on its social media. Which violence do we condemn more frequently and more strongly, the violence of the social uprising (estallido social) or structural violence? Can we hold a plebiscite amid violence? Are we witnessing a de facto process of becoming more parliamentary? How can we return to pacted democracy (democracia de los acuerdos) and overcome this polarization?…Is it better to debate the philosophical or bureaucratic elements of the new Constitution?

Although they do not admit it publicly, in this bubble the political elites have already spun happy tales (and sad ones) about their future electoral prospects. Some slept soundly last night, convinced that the constituent process managed to institutionally corral the social conflict. Others surely had nightmares thinking about “Chilezuela” or an “Argentinized” future. Today, some woke up planning how to relocate their families and investments.

On the other side, infinitely more populous and poorer, the rest of the country feels like they gave a beating to Chile’s masters (dueños), the “coalition of abusers” [made up of the political system and corporations]. Using the numbers and metrics of the system, this electoral beating without a doubt destroys the self-sustained complacency with the status quo and its roots in the Constitution. The mobilization of young voters, women, and residents of popular sectors who put their frustrations and their hopes into the ballot box seem to explain this result. But without institutional channels and organizational structure in the medium term, electoral victories, like marches, become diluted. The vote [on October 25] was an “easy” vote, because it was a vote against the system. It was a destituyente vote—a vote for dismantling old structures.

As a result, today we face a historic opportunity to build a more inclusive, less fractured country. However, seizing this opportunity involves understanding and resolving a fundamental and difficult problem: it requires transforming a destituyente movement into a Convención Constituyente. [Translator’s note: in addition to voting to rewrite the Constitution, voters chose for the new Constitution to be drafted by a citizen-elected, citizen-led convention]. And make no mistake: The dynamics of the political system we have seen in recent months are not promising. Congratulating themselves for having contained the uprising electorally, political leaders have irresponsibly “presidentialized” and polarized the political debate in recent months, often infantilizing the population. A significant chunk of the business class also bought into the polarization line and dug in, threatening and instilling fear in the people and in their own sector from their homes in the three comunas.

In a context of high polarization (which is not the same as affiliation with a party or ideology), rage and hope managed to mobilize a little more than 50 percent of the electorate. And this turned out to be enough to deliver an electoral defeat. The diverse support for this vote should shake up the bubble: more than the triumph of one political sector over another, it’s an anti-establishment cry. Whoever feels like a winner within the three comunas is not reading the situation properly. This outcome cannot even be read as a defeat of a president who has become even more irrelevant than unfit. And that’s saying a lot.

Today, the political parties are empty shells, loose coalitions of ambitions and autocratic aspirations (caudillismos). Some are divided into bunches of friends from high school or university. They are very efficient in reproducing personal loyalties in unequal territory, but they lack collective projects and broad, programmatic, moderately coherent visions. It’s better not to talk about territorial organizations beyond the district offices of local strongmen (caudillos). This is a sign of the times at a global level, but in Chile this reality has been consolidating since the transition to democracy, and today it is reflected in the deep illegitimacy of the system, its stakeholders, and their discourses and practices. Many appear suspect, whether for a corruption scandal, for having direct and indirect ties to a certain last name, or for having betrayed their promises. Now, being perceived as part of the elite (and from the three comunas) also weighs on them. How can we structure a broad debate about the county, its political organization, and its development model with this political party infrastructure? How can we avoid having to choose between people who compete with each other every day for our attention in ever more unconvincing and empty ways?

Although it seems counterintuitive, we have to try to isolate the constituent assembly from political parties and the upcoming electoral races at the local, regional, and national levels. This is perhaps the only way it may be possible to elevate and complicate the outlook and the debate, in order to negotiate what is needed. The difficulty lies in the fact that the potential for successfully insulating the constituent process and conventional electoral politics depends on the parties and their leaders. The grand narrative and legitimacy that the plebiscite created penalizes those of the three comunas. But they have lobbies, the media, social media, and campaign financing on their side. They win by default, even though they lack legitimacy. They don’t have power, but for now, they still keep their seats.

If the uprising hadn’t already achieved it, the result of the plebiscite should make clear that, although the elites win, it is no longer possible to control a country from and according to the logic of the three comunas. The gulf between the two Chiles did not only become politicized in the streets, but also at the ballot box. And although they don’t yet have candidates or a political program, those who experienced the power of voting for the first time during the plebiscite will at least keep exercising their power to dismantle—their destituyente power. Even if it’s only a defensive strategy, the plebiscite should make the political parties and those of the three comunas want to open up spaces, share power, and sit down as equals with representatives of the part of Chile they ignore and disdain in order to negotiate a model for the country. Or they can just observe, with good intentions, but based on metrics with painfully strident blind spots.

A constituent assembly that privileges the discourses and patterns of competition of recent months, that features the same familiar faces, and that sees specialists and legal experts from the three comunas painstakingly debate will risk frustrating expectations. Sooner or later, that frustration will end up playing against [the elites]. Designing a firewall between the constituent assembly and everyday politics means restricting the representation of those who, in the plebiscite, wound up being a stark minority in their three comunas. It means favoring those who, until now, despite being many, have only been able to express themselves in the negative [by voting to do away with the vestiges of the Pinochet era]. Rapidly implementing this firewall is both difficult and indispensable in the process that has now begun and that inevitably, to be successful, must be inclusive.

Translated by Néstor David Pastor and Heather Gies.

Juan Pablo Luna has a PhD in Political Science from the University of North Carolina. He is professor at the Institute of Political Science and the School of Government at the Pontifícia Universidad Católica de Chile, associate researcher at the Millenium Institute for Foundational Research on Data, and researcher at the Center for Applied Ecology and Sustainability (CAPES).

This article is part of the project CIPER/Académico, a CIPER initiative that seeks to bridge academia and public debate.